Maria Island, situated off the east coast of Tasmania, holds a rich and complex history, particularly tied to Dutch exploration. Its story is interwoven with Indigenous heritage, European exploration, and a brief period as a convict settlement.

Dutch exploration

Maria Island was first sighted by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642 during his historic voyage to chart the unknown southern lands. Tasman named the island after Maria van Diemen, the wife of Anthony van Diemen, the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. This act of naming underscored the strategic and symbolic importance of Tasman’s mission to expand Dutch influence and knowledge of the region.

Tasman’s brief encounter with Maria Island was part of a broader effort to map and claim territory for the Dutch Republic. Although his interaction with the island was limited, the naming remains a significant legacy of Dutch exploration in the Southern Hemisphere.

Journal of Abel Tasman

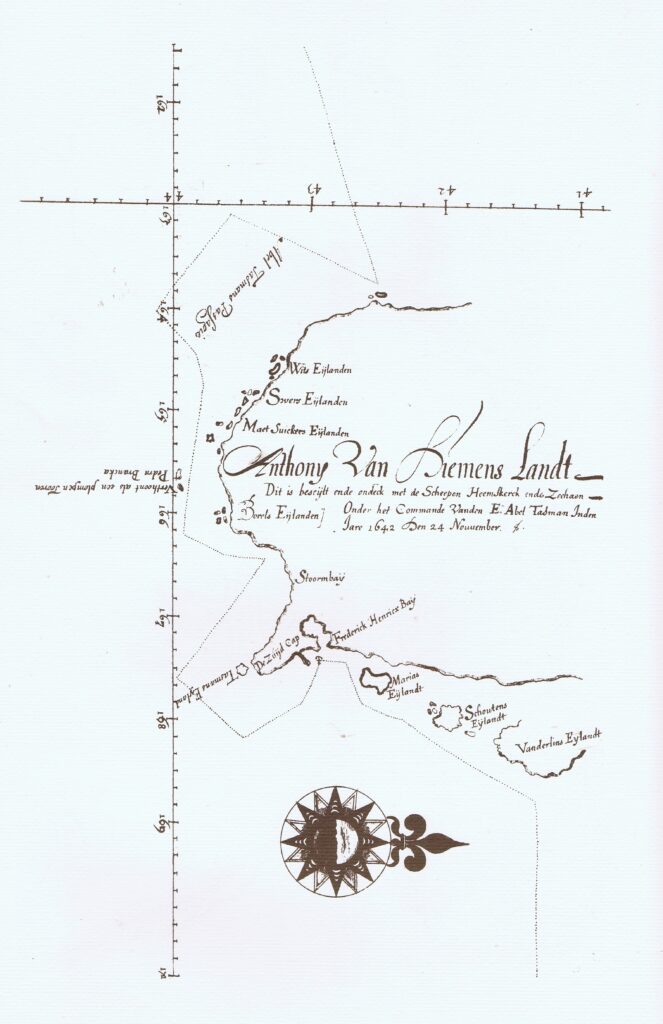

Excerpts from the Journal of Abel Tasman – how Maria Island became known to Europeans. Essentially, the only reference is on a map drawn by Tasman in December in 1642. Maria was the name of the wife of Anthony van Diemen.

In 1642, Abel Tasman sailed the Southern Ocean at the behest of the VOC, essentially to find money making opportunities.

The map shows that he charted approximately half of the west coast and all of the south coast of Tasmania, naming various islands as he went. Eventually he anchored in a bay near the present town of Dunalley.

“3 December

In the afternoon we went to the south-east side of this bay in the boats aforesaid, having with us Pilot-major Francis Jacobs. Skipper Gerrit Jansz, Isack Gilsemans, supercargo on board the Zeehaen, sub-cargo Abraham Coomans, and our master carpenter Pieter Jacobs; we carried with us a pole with the Company’s mark carved into it, and a Prince-flag to be set up there, that those who shall come after us may become aware that we have been here, and have taken possession of the said land as our lawful property.

We then ordered the carpenter aforesaid to swim to the shore alone, with the pole and the flag, and kept by the wind with our pinnace; we made him plant the said pole with the flag at top into the earth, about the centre of the bay near four tall trees

Our master carpenter, having in the sight of myself, Abel Jansz Tasman, Skipper Gerrit Jansz, and Subcargo Abraham Coomans, performed the work entrusted to him, we pulled with our pinnace as near the shore as we ventured to do; the carpenter aforesaid thereupon swam back to the pinnace through the surf. This work having been duly executed, we pulled back to the ships, leaving the above mentioned as a memorial for those who shall come after us, and for the natives of this country …”

Planting the flag was largely a symbolic gesture. Beside this written account, we would never know the deed had been done. Nobody seems to have taken any notice. It would be another 150 years before the next European came by, and the natives have no account in their oral history.

“4 December

At noon Latitude observed 42˚ 40’, Longitude 168˚, course kept north-east, sailed 8 miles; in the afternoon the wind turned to the north-west; we had very variable winds all day; in the evening the wind went round to west-north-west again with a strong gale, then to west by north and west-north-west once more; we then tacked to northward, and in the evening saw a round mountain bearing north-north-west of us at about 8 miles’ distance; course kept to northward very close to the wind. While sailing out of this bay and all through the day, we saw several columns of smoke ascend along the coast. Here it would be meet to describe the trend of the coast and the islands lying off it, but we request to be excused for briefness’ sake, and beg leave to refer to the small chart drawn up of it, which we have appended.”

The 4th of December is the account of travelling north from Dunalley. MARIA ISLAND is accounted for in the line “… the coast and the islands lying off it, …”. It is noted and labelled on the chart, although the chart is not as accurate as most of Tasman’s work.

“5 December

In the morning the wind blowing from the north-west by west, we kept our previous course; the high round mountain we had seen the day before, now bore due west of us at 6 miles’ distance; at this point the land fell off to the north-west, so that we could no longer steer near the coast here, seeing that the wind was almost ahead. We therefore convened the council and the second mates, with whom after due deliberation we resolved, and subsequently called out to the officers of the Zeehaen, that pursuant to the resolution of the 11th ultimo we should direct our course due east, and on the said course run to the full longitude of 195˚ or the Salamonis islands, all which will be found set forth in extenso in this day’s resolution”.

Sailing in a northerly direction is no longer possible at this point because of the wind conditions, so Tasman turned to the east, eventually to make landfall in New Zealand.

Although Tasman didn’t buy, sell or swap anything, his map making was important for European knowledge. His work is incorporated in the Blaeu world map, composed in 1645-1646. This map, measuring 276 x 173 cm, hangs in the Maritime Museum in Rotterdam.

annotations: Kees Wierenga

Maria Island as a national park

In 1972, Maria Island was declared a national park, reflecting its ecological and historical value. The Darlington convict site was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2010 as part of the Australian Convict Sites, underlining its historical importance. Today, the island’s legacy of Dutch exploration and its subsequent chapters are preserved for study and reflection.