The life of Arie Stiermann is a poignant reflection of the upheaval and resilience experienced by many Dutch migrants in the aftermath of World War II. His story spans persecution under Nazi rule, postwar trauma, and the search for a peaceful life in Australia—one marked by both hardship and hope.

A survivor of Buchenwald

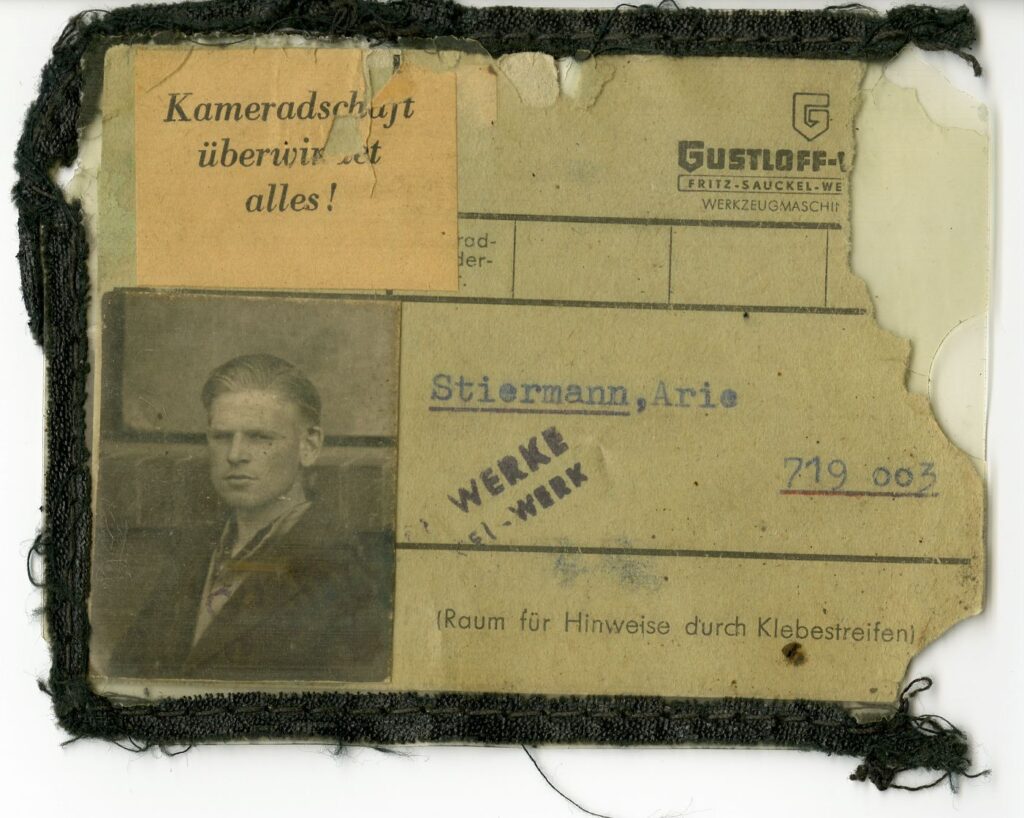

Born in the Netherlands, Arie Stiermann was taken from Rotterdam during the Nazi occupation and interned in Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany. Like many prisoners, Arie was subjected to forced labour. His identification card, now held by the History Trust of South Australia, bears the logo of Gustloff-Werke, a Nazi armaments company that operated inside the camp and used prisoner labour to manufacture rifles and artillery parts.

The card also includes the chilling slogan “Kameradschaft überwindet alles” (Comradeship conquers all), a bitterly ironic motto amid the brutal conditions of Buchenwald. Despite these horrors, Arie survived until the camp’s liberation in April 1945.

In the chaotic days that followed, with the Soviet occupation of Weimar looming, Arie married a German woman he had met after liberation. The couple fled hastily by train to the Netherlands, leaving behind only a brief message with her parents—relayed by chance through a neighbour also at the station. The couple would not see her family again for 15 years, finally reuniting in East Germany.

Postwar prejudice and emigration

Despite his survival, life in the Netherlands was far from easy. Arie’s wife, being German, became the target of widespread postwar prejudice—a common experience for families seen as “mixed” in the war’s aftermath. This social stigma contributed to the family’s decision to emigrate in 1963.

At the age of 41, Arie departed with his wife and four children aboard a ship bound for Australia. The family first arrived in Port Melbourne, then continued by train to Adelaide, where they were temporarily housed at the Glenelg Migrant Hostel on Warren Avenue. After a brief stay in Glenelg, they settled permanently in Christies Beach, where Arie and his wife raised their family.

Quiet resilience in Australia

Arie rarely spoke of his wartime experiences, although fragments of memory emerged over time. One such memory included a surreal moment after the camp’s liberation: former prisoners, including Arie, were reportedly permitted to loot areas of Weimar within restricted hours. He recalled breaking into the office of a local Bürgermeister (mayor), stealing a copy of Mein Kampf and a carved deer ornament. He later exchanged the book with a Jewish newsagent in Rotterdam—for a football magazine.

Though shaped by trauma, Arie’s postwar life was defined by quiet resilience. He lived in Christies Beach for decades and passed away in 2020, leaving behind a story that connects the Netherlands, Germany, and Australia—echoing broader themes of survival, prejudice, migration, and community.

A story preserved

Thanks to the efforts of the History Trust of South Australia, Arie Stiermann’s identification permit and accompanying history are now preserved as part of the “From Many Places” collection, which documents the journeys of migrants who came to South Australia after WWII.

The preservation of his story not only honours Arie’s legacy but also contributes to a deeper understanding of the diverse paths Dutch migrants have taken to Australia—and the profound personal histories that lie behind each arrival.

References:

- History Trust of South Australia, “Identification permit belonging to Arie Stiermann”, Accession No. HT 2024.0175. Link to source

- Migration Museum, South Australia, part of the History Trust of South Australia

- Arolsen Archives (for broader Buchenwald context): www.arolsen-archives.org