Operation Lilliput took place during the Battle of Milne Bay was the first time that Allied Forces were able to stop the Japanese advance in the Pacific. While the Battle is well recognised, the Dutch participation in the battle is not very well known.

Also important to mention here is that the successes of the Allied Forces at the Battle of Milne Bay would not have been possible without the Allied guerrilla forces on the island of Timor. They were able to tie down the Japanese forces and this weakened their invasion plans for New Guinea.

This the abstract from the book Allies in bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two. By Dr Jack Ford

Dutch involvement in Operation Lilliput

Dutch ships provided MacArthur with a sea transport capability. This was vital to the success of his planned offensive in Papua. Macarthur’s nemesis US Admiral Ernest King would not allot landing craft or aircraft carriers to the SWPA. MacArthur improvised by building airfields and using the Dutch ships to support his advance along Papua’s coast. Macarthur used the Dutch ships to rush reinforcements to Papua to meet an expected Japanese threat. Convoy ‘ZK8’ delivered the Australian 14th Brigade (4,735 troops) to Port Moresby on 18 May 1942.[i] It was an all-Dutch affair comprising Bantam, Bontekoe, Van Heemskerk and Van Heutsz with Tromp as one of twos escorts.

In July, Tasman brought the AIF 7th Brigade’s vanguard to Port Moresby. MacArthur wanted a strategic airfield built at Milne Bay on Papua’s southeastern tip. Bontekoe and Karsik formed the first convoy to Milne Bay where they arrived on 25 June carrying Australian troops, US engineers and construction gear. Swartenhondt delivered the first RAAF personnel to use the completed Milne Bay airfield.[ii]

On 11 July, Tasman sailed from Port Moresby carrying the 7th Brigade vanguard to garrison Milne Bay. The Milne Bay trips proved uneventful until the Japanese invaded Buna on Papua’s north coast on 21 July and Milne Bay on 26 August 1942. Japanese warships and aircraft sought to prevent Allied reinforcement convoys reaching the battle zones. So escorts more powerful than the small RAN corvettes (e.g. Warrego, Ballarat)were required. The destroyer Arunta escorted Tasman to Milne Bay on 25 August but the ships returned to Port Moresby upon reports of Japanese cruisers seen nearby. Tasman returned to Milne Bay on 1 September with a cargo that “was exceedingly welcome to the [local] military commander.”[iii] Enemy planes attacked her the next day. That night, enemy cruisers entered Milne Bay to evacuate their wounded and ignored Tasman. When on 5 September, Convoy ‘Q2’ comprising s’Jacob, Anshun (British), Arunta and the sloop HMAS Swan reached Milne Bay, the Japanese cruisers were not so distracted. They sank Anshun.

Dutch luck held for the rest of 1942. There were mishaps though. On 4 September,while in Townsville in a convoy that included Cremer and Van Heutsz, Van der Lijn was damaged in a collision with Perthshire.[iv] Japara and Van Heemskerk delivered cargo to Milne Bay on 12 September. An escort of five Allied US destroyers protected them from two nearby enemy destroyers. On 17 September, Van Heutsz and four other merchantmen supplied Milne Bay. The defeat of the Japanese invasion of Milne Bay by 5 September 1942 was the first Allied land victory over the Japanese. This success was attributable to Milne Bay’s Australian and US defenders together with the crews of the (mostly Dutch) merchantmen that had delivered vital supplies and reinforcements to the garrison.

The Dutch ships gained greater importance during the Buna Campaign that began on 29 October 1942. Allied troops attacking Buna had supply difficulties. Supplies were brought forward along the Kokoda Track by Papuan carriers or by transport aircraft to Dobodura airfield near Buna. Neither method could deliver large amounts of supplies. In mid-November 1942, a system of convoys was organised to land supplies at Oro Bay close to the Buna frontline. Designated ‘Lilliput’, the convoys were loaded in Australia; sailed to Port Moresby; then on to Milne Bay; before being split into ship pairs escorted by corvettes for the final run into Oro Bay. Two merchantmen at a time were sent due to Oro Bay’s limited facilities.

During ‘Lilliput’, the US Government was sometimes critical of the performance of the Dutch ships. It took a dim view of any delays in getting the ships underway, even though Australia’s militant waterside unions were often the cause. Van Holst Pellekaan requested that Washington be informed by the ACSC that Dutch vessels were carrying 75% of all cargo taken to New Guinea.[v] Conditions on the ships were often makeshift. Three members of the New Guinea Air Warning Wireless Company (NGAWWC) aboard the s’Jacob described her as “a mobile refrigerator ship and certainly no passenger vessel as far as comfort was concerned.”[vi]

The first ‘Lilliput’ convoy was largely Dutch comprising Maetsuycker, Cremer, Bontekoe, Japara, Bantam, Both, Balikpapan plus Australia’s J.B. Ashe, Jesse Applegate, escorted by Arunta, Ballarat and the corvette HMAS Katoomba. The convoy left Townsville on 15 November. Japara, Bantam and Balikpapan were selected to make a trial run to Oro Bay. They reached Milne Bay on 19 November. Japara made the first supply trip to Oro Bay on 18 December.[vii] She set the pattern for the rest of ‘Lilliput’. The Dutch ships participating in ‘Lilliput’ were Balikpapan, Bantam, Bontekoe, Both, Janssens, Japara, Karsik, Maetsuycker, Patras, Reijnst, s’Jacob, Swartenhondt, Tasman, Thedens, Van den Bosch, Van Heutsz, Van Outhoorn, Van Spilbergen and Van Swoll.[viii] This was 19 of the 27 Dutch ships allotted to the SWPA by January 1943. Almost without exception, the merchant ships of `Lilliput’ were Dutch. Only five other merchantmen participated in the convoys. These ships substituted for the landing craft that MacArthur could not get from the US Navy. It was not until the end of the ‘Lilliput’” convoys in June 1943 that the first amphibious-capable Liberty ship, the US Key Pittman appeared at Oro Bay. In the vital stage of ‘Lilliput’, (December 1942 to February 1943), only Dutch ships only were used. Over 18 trips, these 12 ships delivered 2,400 fresh troops and 40,000 tons of badly needed supplies to the Buna Front.[ix] Supplies were loaded at Sydney or Brisbane. From 6-8 January 1943, Bontekoe, Cremer, Japara and Tasman berthed at various wharves on the Brisbane River.[x]

‘Lilliput’s’ success was not without loss. As most ships belonged to KPM, the Dutch correspondingly suffered the worst from enemy attacks. Japanese air cover over Papua endangered the ‘Lilliput’ ships. The first 1943 convoy comprised Van Heutsz escorted by Katoomba. On 9 January, four Japanese dive-bombers attacked Van Heutsz at Oro Bay. Van Heutsz took a direct hit on the No.3 hold containing aviation fuel and ammunition plus two near misses before the planes were repelled. The ship’s electrician, the quartermaster and a US soldier were killed.[xi] On 18 March 1943, nine enemy bombers sank s’Jacob in Oro Bay. The first mate of s’Jacob and four others died while the majority of the 72 passengers aboard suffered wounds.[xii] Karsik was nearby. She was attacked by nine bombers but was unscathed. On 28 March, a force of 40 Japanese bombers sank Bantam and Masaya (US). Bantam was hit by seven bombs that killed seven crewmen and wounded many others including Captain Mulleanaux.[xiii] He organised his surviving crew “amid the roar of the flames and the escaping steam”, to “subdue the flames” and “get the ship away from the jetty.”[xiv] Bantam grounded and became a total loss. An enemy bomber was shot down.[xv] Bantam survivors were transferred to Van Outhoorn on 29 March and were sent to Sydney’s Princess Juliana Hospital. The last Dutch loss during ‘Lilliput’ was on 14 April 1943 when Van Heemskerk was sunk in a Milne Bay air raid. Nine bombers attacked Van Heemskerk, Balikpapan, Van Outhoorn and Gorgon (British). As Van Heemskerk was unloading when the raid began, 20 US soldiers on a jeep mounting a 50-calibre machine gun was hoisted aboard to provide AA cover. Two US soldiers were killed, while seven US troops and 10 crewmen were wounded.[xvi]Van Outhoorn took two near misses that seriously damaged the hull with 8 crewmen dead and 12 crewmen and 6 US soldiers wounded.[xvii] Balikpapan claimed two enemy bombers.

The loss of three ships (total 8,225 tons) in over a month alarmed the Dutch. KPM Maintenance Superintendent Hermanus Koning inspected Van Outhoorn at Oro Bay on 29 April 1943. His report condemned the conditions under which the ships were forced to operate. He complained there was “little or no appliance to save ships in any New Guinea ports”; that there were “no firefighting appliances or salvage pumps to keep a ship afloat if she is hit”; that Milne and Oro Bays had “no suitable tug-boat to assist ships” and this had contributed directly to Bantam‘s loss; and damning of all, that some ships were “sent from Port Moresby or Milne Bay to Oro Bay without [air] escort.”[xviii] KPM sent an official protest to the Naval Officer-in-Charge at Port Moresby. Dutch voyages to Oro Bay were temporarily suspended. The captain and officers of Bontekoe refused to take her any further than Milne Bay. As the Dutch knew that their ships were needed, the issue was quickly resolved by increased Allied air cover. Bontekoe was already back at Oro Bay on 24 April.[xix] On 14 May 1943, 20bombersattacked Reijnst and Thedens in Oro Bay.[xx] The ships were undamaged. Allied fighters destroyed seven bombers.

The Dutch tried to salvage their ships. Van Outhoorn was sent to Sydney for repairs but efforts to salvage Bantam failed. KPM sent salvage expert Captain Noorden to Oro Bay in May. He confirmed to Lammers and the ACSC that the ship could be saved rather than leaving it as a coal hulk in Milne Bay as the Australians wanted. In 1944, Bantam was raised and towed to Sydney. After it was found that it would cost nearly £40,000 to refit the ship, the NEI Commission gave her to the RAN as a target hulk.[xxi] Australia was approached to replace the Dutch shipping losses. Governor General of the NEI Hubertus Van Mook had requested this in writing on 3 December 1942. He inquired whether the ships could be rebuilt in Australia given “the enormous losses of the KPM fleet during operations in the Netherlands Indies (60% of the fleet) and since then, especially in Australian waters.”[xxii] He required 2,000-ton ships for use in NEI coastal waters during and post-war. As an incentive for Australian support, van Mook stressed that not only was a considerable number of ships to be built in Australia but also, they would be used to carry increased post-war trade between the two countries. The Australian Government finally replied on 2 May 1943. Curtin’s reply clarified that Australia was interested in the Dutch proposal due to its benefits to local industry and trade, but that Australian shipyards were too busy with war-work to handle building ships for KPM.

‘Lilliput’ ended in mid-June 1943. It had comprised 39 convoys run in 40 separate stages that delivered 3,802 reinforcements and 60,000 tons of supplies, mostly on Dutch ships.[xxiii]The Dutch role in ‘Lilliput’ was vital. Two special missions illustrate this importance. In December 1942, with Australian and US forces stalled at Buna, tanks were needed to destroy the Japanese bunkers but there were no suitable landing craft in the SWPA for delivering tanks. The solution was to use Karsik. She had been a shallow-draft train ferry at Batavia and could load and unload tanks whereas earlier attempts using other vessels had resulted in the tanks sinking during unloading. Karsik left Port Moresby on 8 December carrying four Stuart light tanks from the Australian 2/6th Armoured Regiment. She delivered them to Oro Bay on 11 December. The voyage was codenamed ‘Karsik’. Pleased with this success, the Allies requisitioned Karsik plus Japara to bring another four tanks to Oro Bay on 16 December in the ‘Tramsik’ voyage. The tanks arrival at Buna enabled the Australians to penetrate the Japanese defences on 18-19 December 1942. This improved the Allied troops’ sagging morale. The other special mission was as part of ‘Operation Accountant’ in February 1943. Bontekoe, Karsik and Van Heemskerk carried the US 162nd Infantry Regiment from Australia directly to Oro Bay. This regiment was the vanguard of the US 41st Division that relieved the US 32nd Division stalled outside Buna. The Dutch ships delivered 3,200 fresh US troops to Buna from 21 February to 4 March 1943.[xxiv]

Australia and the USA recognise the Dutch ships’ valuable service in MacArthur’s first offensive in the SWPA. Tributes are paid in their official war histories. The Australian naval history states:

“Lilliput” itself remained a monument to the fine service of the Dutch ships which, almost without exception, constituted its transport side. Their contribution was invaluable and during the period of “Lilliput” they were irreplaceable. But the strain of the air attacks, and the loss of three of the ships were telling, particularly on their native crews….[xxv]

The official US naval history covering the Buna Campaign praised the Dutch ships, commenting:

Of 2,500 to 4,500 tons burthen, they were officered by outstanding Dutch seamen, and were manned by the most part by Javanese – whose stoical and fatalistic attitude towards air attacks made for reliable crews. …Nobody slept on these voyages. At night the ships snaked through the reefs. By day they dodged Japanese bombs and strafing bullets. On 16-17th November 1942, four ships sank under bombing attack, the supply line interrupted, and a planned advance by the 32nd Division was delayed three weeks.[xxvi]

The official US Army history states:

[The Dutch] …their greatest contribution was a merchant marine, a part of the Koninklijke Paktevaart Maatschappij, better known as the KPM Line… they were to play a major role in the supply and reinforcement of the Southwest Pacific Area’s outlying positions.[xxvii]

Paul Budde

[i] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.63.

[ii] Douglas Gillison, Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942: Australia in the War of 1939-1945 (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1962), p.564.

[iii] KPM, The Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij (KPM Lines) and the War in the South West Pacific, p.1.

[iv] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 479J, Van der Lijn, Van der Lijn captain’s protest lodged with Netherlands Vice-Consul A.S. McNaught in Townsville, 7 September 1942.

[v] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 193C, Allied Consultative Shipping Council, 16th ACSC meeting minutes 10 March 1943.

[vi] Alex E. Perrin, The Private War of the Spotters: A History of the New Guinea Air Warning Wireless Company February 1942-April 1945 (Foster, VIC: NGAWW Publication Committee, 1990), p.143.

[vii] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.262.

[viii] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.269.

[ix] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, pp.268-269.

[x] Roger R. Marks, Brisbane WW2 v Now No.7 “Brisbane River-upstream from Bretts”, (Brisbane: R.R.Marks, 2005), pp.19-21.

[xi] NA files, Series MP1587/1, Item 319C Bombing of Van Heutsz 1943, Van Heutsz report 9 January 1943; & Item 485B Van Heutsz, Newcastle’s Staff Officer (Intelligence) to Director of Naval Intelligence, report 21 January 1943; & Item 482W s’Jacob, commander of Bendigo to Naval Board Secretary, report 12 March 1943.

[xii] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 482W, s’Jacob, Commander Katoomba to Naval Board Secretary, report 10 January 1943.

[xiii] NA files, Series MP1587/1, Item 156E Bantam and Masaya loss by Japanese aircraft, Arrivals and Departures Bantam supplied by agents John Sanderson & Co; & Item 476W, Bantam, Port Moresby’s NOIC (Naval Officer in Charge) to Townsville’s NOIC, cipher 29 March 1943.

[xiv] KPM, KPM Lines, p.3.

[xv] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 476W, Bantam, HMAS Bowen to Port Moresby’s NOIC, cipher 29 March 1943.

[xvi] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 156G, Van Heemskerk, Milne Bay’s Naval Intelligence Officer to Port Moresby’s Staff Officer (Intelligence), report 17 April 1943.

[xvii] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 485C, Van Outhoorn, List of casualties SS Van Outhoorn 14 April 1943.

[xviii] NA file, Series MP1587/1, Item 156G, Van Heemskerk, Townsville’s Naval Intelligence Assistant to Townsville’s Staff Officer (Intelligence), report 29 April 1943.

[xix] Ron De Mes, to author, letter 23 May 2013.

[xx] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.283.

[xxi] NA file, Series MP456/4, Item 1943/151, Casualty Bantam Oro Bay, Bantam Salvage Board report 23 May 1943.

[xxii] NA file, Series A989, Item 1943/600/9, Construction of NEI Ships in Australia, Van der Plas, memo 2 May 1943.

[xxiii] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.269.

[xxiv] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, pp.269-270.

[xxv] Hermon Gill, Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, p.283.

[xxvi] Samuel Eliot Morison, Breaking the Bismark’s Barrier 22 July 1942-1 May 1944: History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II Volume VI (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950), p.37 & p.47.

[xxvii] Samuel Milner, Victory in Papua: United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific (Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of Army, 1957), p.26.

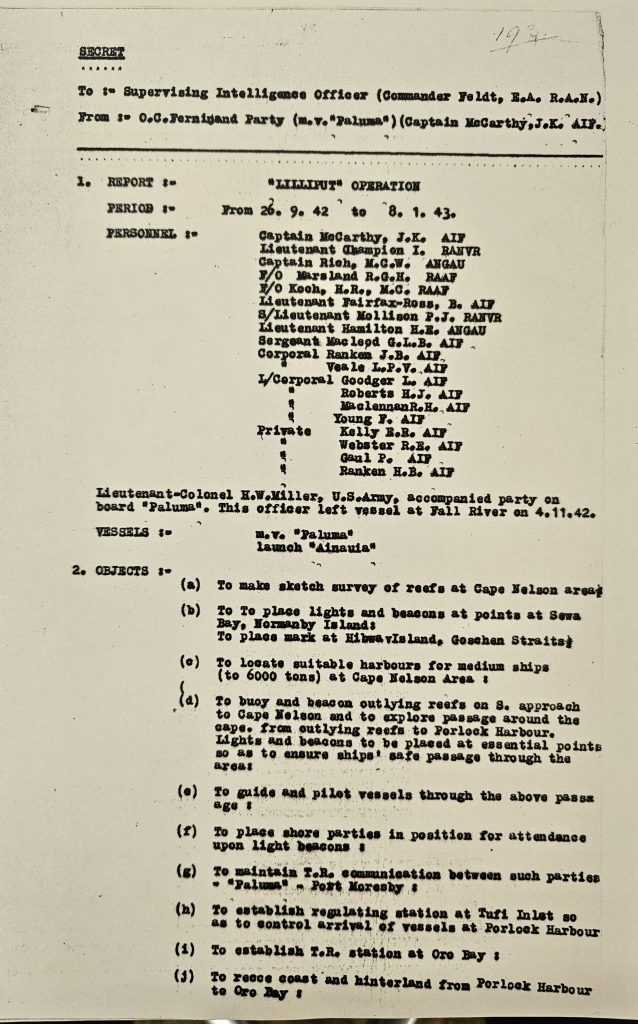

The State Library of Queensland holds a file from the “MacArthur Era Trust Photographs and Records”, this also includes a range of documents on the Lilliput operation. This is the first page of that document. It is a US document and doesn’t contain information on the Dutch participation as mentioned above.