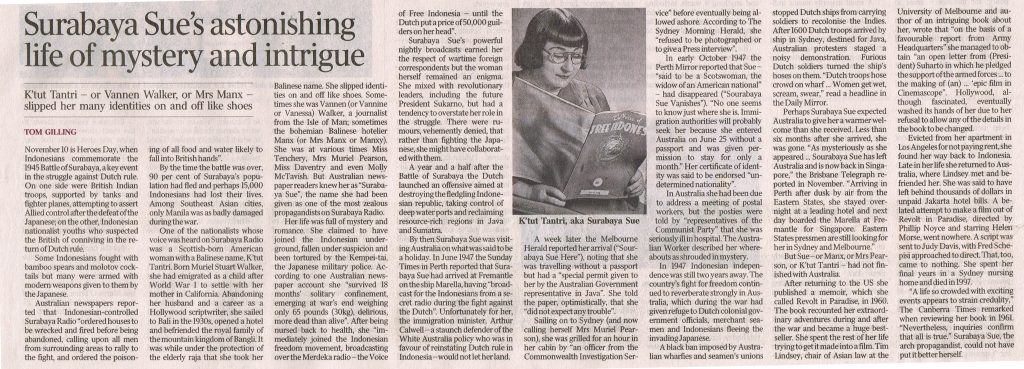

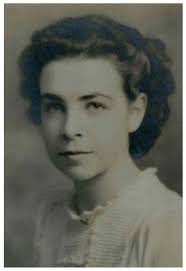

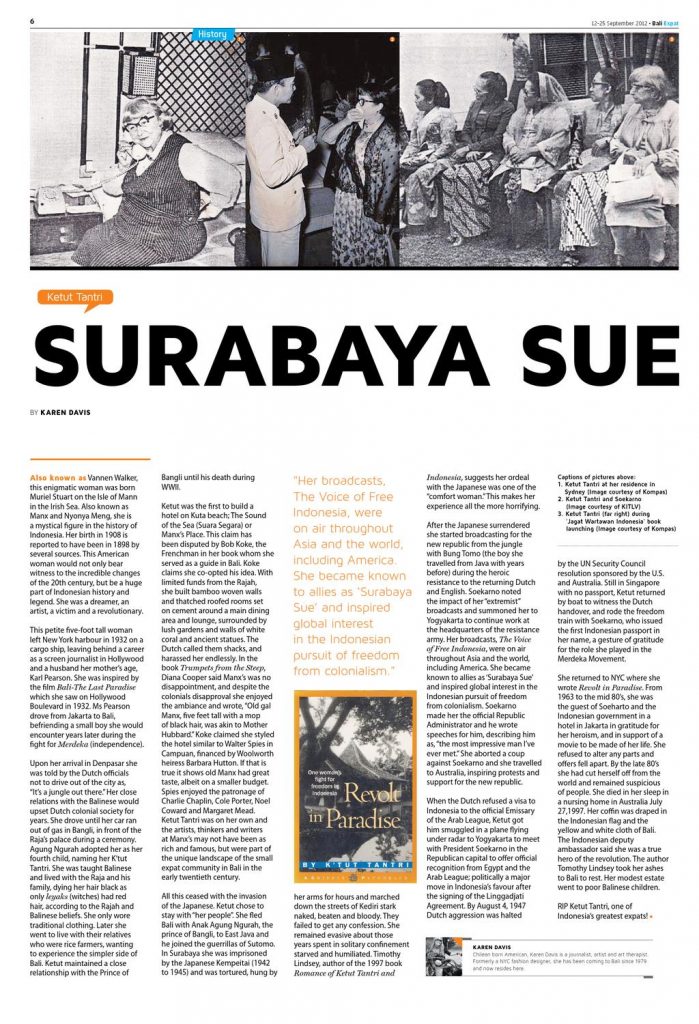

Muriel Stuart Walker, alias K’tut Tantri, alias Surabaya Sue and known under at least half a dozen other names was born on 19 February 19, 1898, in Glasgow, she died on 27 July 1997 in Sydney.

She is best known for her work as a radio announcer for the Voice of Free Indonesia in Surabaya, in the Republic of Indonesia during the Indonesian National Revolution. The foreign press gave her the name Surabaya Sue.

She immigrated together with her mother from Scotland to California after the First World War. Between 1930 and 1932 she worked as a playwright in Hollywood and married an American named Karl Jenning Pearson.

In 1932, she left the United States to start a new life on the Indonesian island of Bali, at that stage part of Netherlands East Indies, where she spent the next fifteen years and took the name K’tut Tantri. Here she attracts the attention of Prince Anak Agung Nura, who introduces her to his language and culture, and begins what will become a lifelong friendship.

She spoke fluent Balinese and some other Indonesian languages and developed great sympathy for the Indonesians and dislike of the Dutch, whom she saw as arrogant settlers. She started one of the first hotels in Kuta in 1936 and met several Western artists there, including Walter Spies and Adrien le Mayeur.

When the Japanese landed in Bali in 1942 she joined the Prince in the resistance movement. On the run for the Japanese she escaped to Surabaya. Here she became the radio announcer for an illegal Indonesian freedom fighters group led by a man named Sutomo. She began to establish contacts with several people sympathetic to the anti-Japanese movement. She became known by the press in Singapore, Australia, and the Netherlands as Surabaya Sue.

However, she was caught by the Japanese and had to undergo months of interrogations, even torture and was told she would be executed, but she remained tight-lipped. She was close to death and only weighing 30 kilos when she was brought to a hospital. Here she heard the news that the Indonesian freedom fighters proclaimed their independence as soon as Japan surrendered (August 1945).

Her underground activities and a steadfast attitude to not give in during interrogations led the Indonesians to release her. she was given a choice: return to her country or join the Indonesian fighters. She chose the second option and was entrusted with managing the radio broadcasts for Merdeka (freedom). Her voice was on the air every night. In her radio broadcasts she was very fierce and aggressive towards the Dutch colonial system and the military presence of the British in Indonesia.

When the Indonesian government moved to Jogjakarta, she also moved there. Here she worked in the office of the Minister of Defense. She once wrote Soekarno’s speech. She also she became involved as an espionage agent who managed to trap a gang of traitors.

In a press conference attended by journalists and correspondents of various foreign news agencies and mass media, she was chosen by the government to tell the story of how the people were so eagerly supporting the independence cause, to counteract the Dutch propaganda that the Soekarno-Hatta government was not supported by its people.

She illegally travelled to Singapore and Australia, under a range of different names – always on the run for the authorities who refused to provide her with a traveling visa – to campaign for international solidarity. In Australia she received the support of Australian Unions who had instigated the Black Armada, a boycott of all shipping from Australia to Indonesia. At that time the Netherlands was using Australia as a staging camp to re-colonialise the Netherlands East Indies.

Despite her contributions to the Indonesian nationalist cause, the Indonesians were uncomfortable with her unorthodox lifestyle and her exaggerated claims for attention. This led them to smuggle her out of Indonesia to Singapore in 1947, officially on the pretext that the Dutch would try to arrest her at the first opportunity.

She goes back to the United States, where she published her memoir Revolt in Paradise in 1960. This book was very successful and was translated into several languages. Plans for a film adaptation did not get off the ground because she refused to accept changes to the text. At a later age she settled in Australia, where she died.

Sources:

Ktut Tantri: A Sensational Woman Behind My Name

See also: