Changi Prison, originally designed to hold 600 inmates, was overwhelmed with around 2,400 internees, including civilians associated with the British and Dutch colonial administrations. Among them were women and children, housed alongside male prisoners of war. Despite being overcrowded, Changi was relatively modern, boasting amenities like flushing toilets, though hygiene remained a concern.

Forced to endure disease, malnutrition, and neglect by their captors, the internees at Changi sought solace and solidarity through various means, including education for children and cultural activities. One remarkable endeavor was the creation of signature quilts by the women internees between March and August 1942. These quilts, comprising squares contributed by different individuals, aimed to alleviate boredom, boost morale, and convey messages to loved ones in other camps.

The quilts, named the British, Australian, and Japanese quilts, were meticulously crafted despite limited resources. The women employed diverse embroidery techniques and motifs, reflecting their individual backgrounds and sentiments. Notably, the quilts served as a means of communication and expression amidst the restrictions imposed by the Japanese authorities.

Following the war, the fate of the quilts varied. The Australian and Japanese quilts eventually came into the possession of British and Australian medical officers, respectively, and were later donated to memorial institutions. The Australian quilt, with contributions from nine known Australian women, was presented to the Australian Red Cross and is now preserved at the Australian War Memorial. Conversely, the British Red Cross quilt is housed at the British Red Cross UK office in London.

The quilts stand as poignant reminders of the resilience and creativity of those who endured captivity during World War II, including Dutch internees, and the enduring legacy of their experiences in Changi Prison.

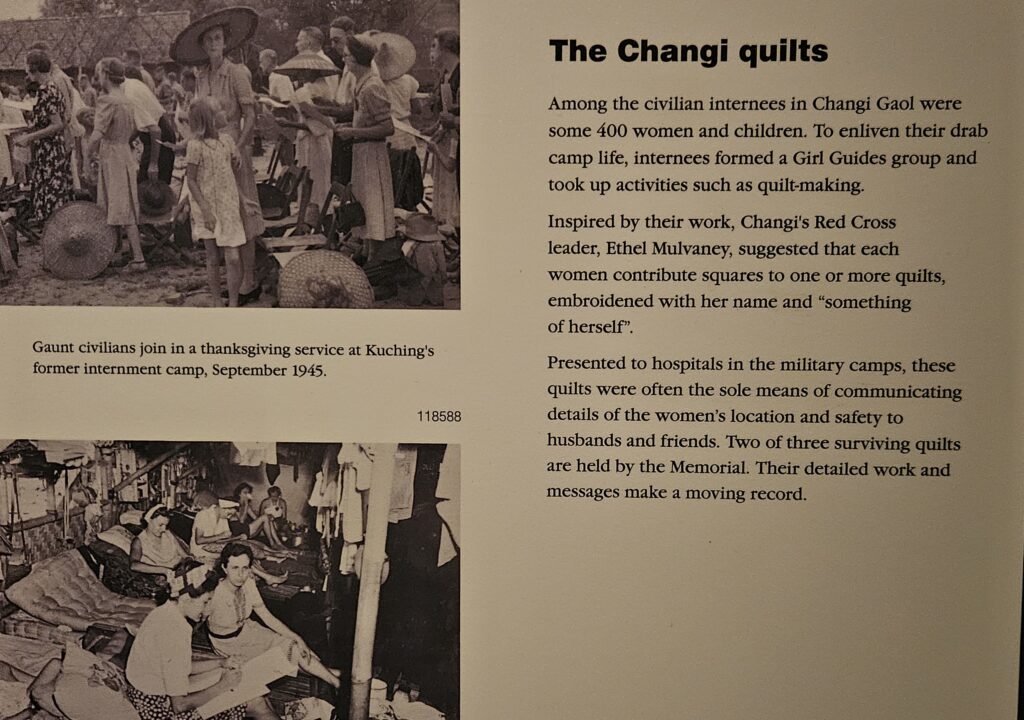

Pictures below are from a display at the Australian War Memorial, taken by Paul Budde April 2024.