The 15th day of August 1945 will go down in history as the day of the end of the Second World War. On that day, Japan capitulated and the President of the United States announced that the conflict in the Pacific was over. But there was no question of a liberation of the Dutch East Indies for the time being.

Unlike in the Netherlands, the cessation of hostilities in that enormous area of the Dutch East Indies was not experienced everywhere at the same time and in the same way. In Dutch New Guinea, the southeastern part had always remained free from domination. On the northern part of the island, on May 2, 1944, the Dutch flag was hoisted next to that of the Americans on the first reconquered area: the attack on Hollandia was successful, as a result of which this place and the area around it fell into Allied hands for good and not long afterwards a stronghold, from which the next leap towards the Philippines and ultimately Japan was made.

In the following months, Wakde, Biak, Noemfoer, Sansapor and a small area of the Vogelkop were successively occupied in Dutch New Guinea, after which the strategically located island of Morotai was attacked and conquered in September 1944.

By now advancing to and conquering the Philippines, the Allies (read: Americans) would cut off the Japanese 16th and 19th armies in the Dutch East Indies, with a total strength of approximately 200,000 men, important oil supplies and war resources from Japan. Another reason for advancing to the Philippines was the discovery by the American 3rd Fleet that the air defenses of the Philippines were significantly weaker than assumed. Thus, the Dutch East Indies were initially left undisturbed so that the Americans could first concentrate on the attack and occupation of the Philippines. The operation began in October 1944 and officially ended in July 1945.

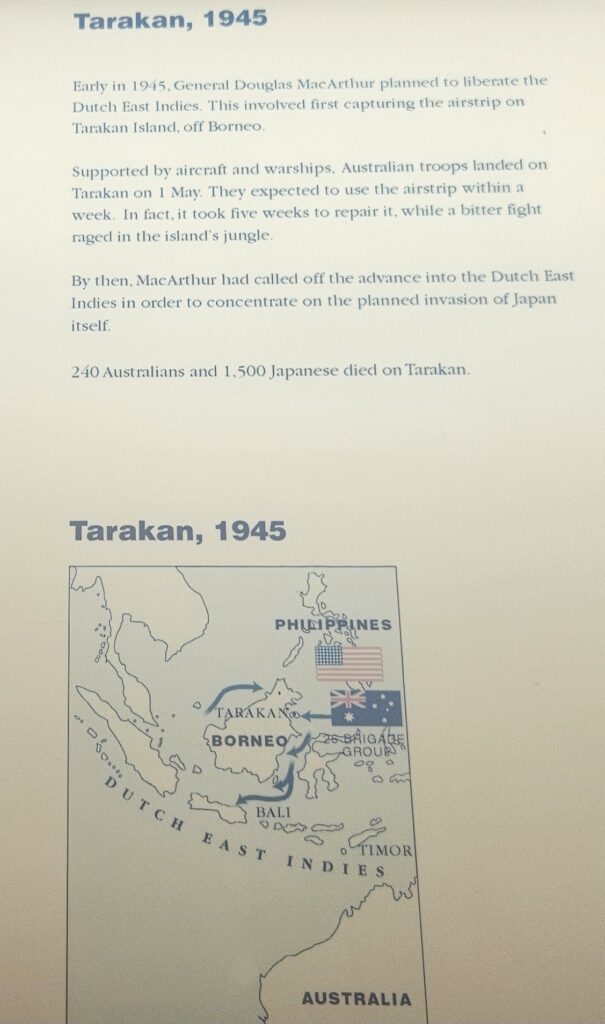

On April 4, 1945, General MacArthur was ordered by Washington to draw up a plan for the attack against the Japanese homeland. In the same assignment he also had to make a plan to occupy the island of Borneo using Australian troops. This would become the last major Allied campaign in the South West Pacific Area. This plan, known under the code name OBOE, was defined as follows: `Early seizure of Java in order to destroy the principal concentration of hostile forces in the Netherlands-Indies; to re-establish the government of the Netherlands East-Indies in its recognised capital and to establish a firm base of operations for subsequent consolidation.‘ The liberation plan consisted of six parts: First on Borneo to liberate in order: Island of Tarakan, the capital Balikpapan and the southern city of Bandjarmas. Than on Java: Surabaya and Batavia Finally the eastern part of the Dutch East Indies and last but not least British Borneo.

Borneo

| Prior to World War II, Borneo was divided between British Borneo, in the north of the island and Dutch Borneo in the south; the latter formed part of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). As of 1941, the island’s population was estimated to be 3 million. The great majority lived in small villages, with Borneo having less than a dozen towns. Borneo has a tropical climate and was mainly covered by dense jungle at the time of World War II. Most of the coastline was lined with mangroves or swamps. Borneo was strategically important during World War II. The European colonisers had developed oil fields and their holdings exported other raw materials. The island’s location was also significant, as it sat across the main sea routes between north Asia, Malaya and the NEI. Despite this, Borneo was under-developed, and had few roads and only a single railroad. Most travel was by watercraft or narrow paths. The British and Dutch also stationed only small military forces in Borneo to protect their holdings. Source: Wikipedia |

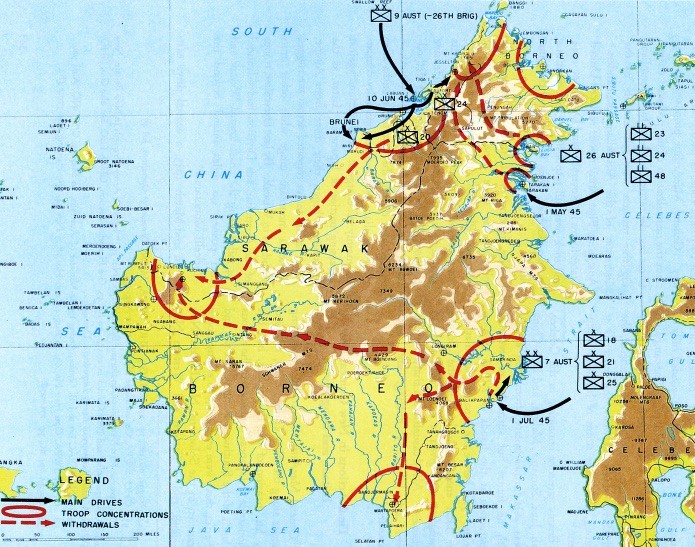

& Oboe 6 – Brunei Bay (10 Jun 45); 7th Div, Oboe 2 – Balikpapan (01 Jul 45) (source: Willoughby, C.A. (ed.), Reports of General MacArthur, Vol. I: ‘The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific’, Washington DC, 1966, p. 384 accessed at: The Australian Experience of Joint and Combined Operations: Borneo 1945 | International Journal of Naval History (ijnhonline.org))

The first landing on Tarakan took place under Australian Lieutenant-General Leslie Morshead on May 1, 1945. The Australian ground forces were supported by US and other Allied air and naval forces, with the US providing the bulk of the shipping and logistic support necessary to conduct the operation. On June 15, Japanese resistance was broken, and a start could be made on consolidating the terrain and preparing an airfield for bombers and fighters for the next attack. Tarakan was conquered by Australian troops, supported by a KNIL infantry company, which acted as scouts and interpreters.

Also operating in the background were personnel from NEFIS (Netherlands East Indies Forces Intelligence Service), who were involved in intelligence gathering and liaison, and NICA (Netherlands Indies Civil Administration), which prepared to re-establish Dutch civil authority following the military campaign. These Dutch units worked under Australian and broader Allied command, marking the beginning of the Dutch return to their former colonial territories.

An Australian soldier rests on a Matilda II tank at Lingkas on Tarakan and reads a letter from home.

In the background on the right is the former Dutch Navy barracks. (Royal Dutch Airforce)

Eight days after the landing, the war in distant Europe ended on May 9, 1945.

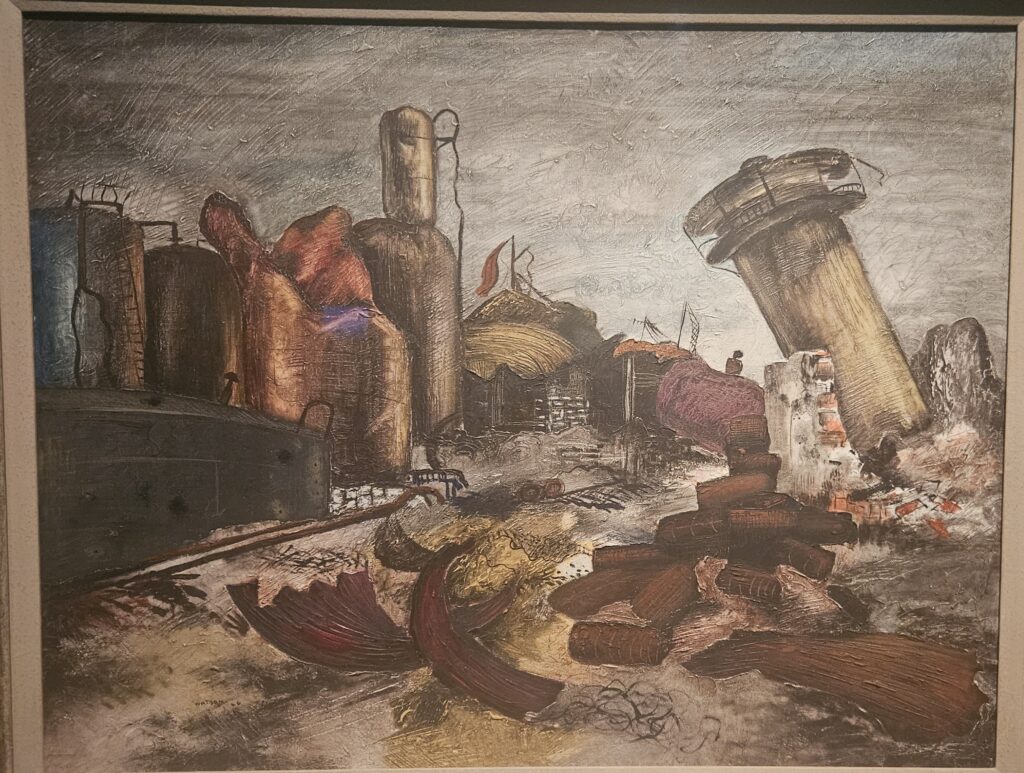

The Battle of Tarakan (Operation Oboe One)

Contrary to the original OBOE plan, the Allies decided to first conquer Brunei on British Borneo. This happened on June 10 and ended on July 14, 1945. This was followed by OBOE 2, and Balikpapan was attacked on July 1, 1945, by the 18th and 21st Brigades of the Australian 7th Division. By the end of July, all objectives on the island of Borneo had been achieved and the ‘Borneo operation’ could be considered a success. Two major naval bases—Brunei Bay and Balikpapan—as well as several airfields were now in Australian hands for potential future operations into Java. The oil fields and refineries of Tarakan, Balikpapan and Miri were also returned to Allied control.

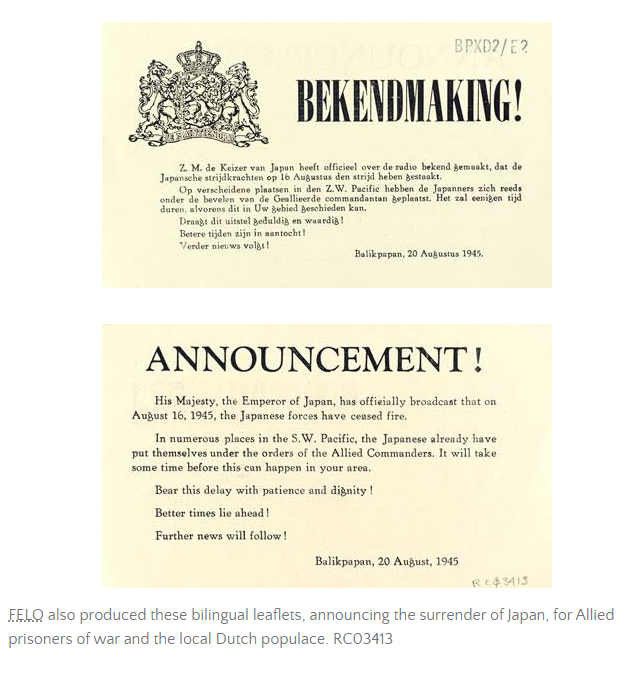

Two weeks later the war in the Pacific ended. On September 2, 1945, the Japanese surrender was ceremonially signed on board the American battleship USS ‘Missouri’ in Tokyo Bay, with the Netherlands represented as an honored and valuable ally.

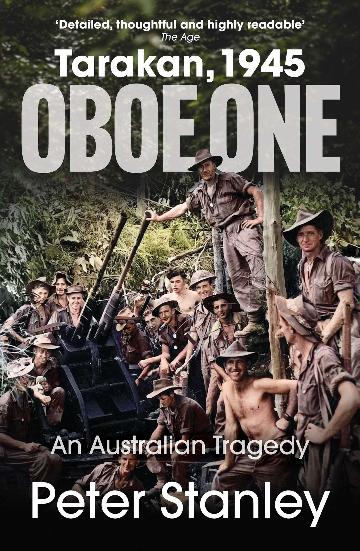

In 1945, the small island of Tarakan off Borneo’s coast became the unlikely stage for one of the Second World War’s most gruelling campaigns. As part of General Douglas MacArthur’s plan to liberate the Netherlands Indies, Australian soldiers launched Operation Oboe One, a mission to capture Tarakan’s airstrip. What was meant to last three weeks stretched into two months of bitter jungle warfare, claiming 240 Australian lives and 1,500 Japanese defenders. The airstrip’s strategic goal faltered, but the courage and sacrifice of those who fought there remain an untold story.

The Bersiap killings

On Java and the other islands the Japanese military were ordered to protect the people in the camps as there were no Allied forces yet available to liberate these places. It was not until July 1946 before the last Japanese troops were evacuated.

Indonesian freedom fighters used the power vacuum left by the retreating Japanese occupational forces and the gradual buildup of a British military presence but before the official handover to a Dutch military presence. This period is known for the Bersiap killings as a result of Sukarno declaring Indonesian independence on 17 August 1945.

During the Bersiap period, thousands of Eurasian people were killed by Indonesian natives. Many people were also killed among non-European groups such as Chinese, Japanese POWs, Koreans and native Indonesians like Moluccans, Javanese, and other people of higher economic standings.

Instances of wanton violence decreased with the departure of the British military in 1946, by which time the Dutch had rebuilt their military capacity, though revolutionary and intercommunal killings continued into 1947. Meanwhile, the Indonesian revolutionary fighters were well into the process of forming a formal military. Despite two Dutch military offensives (Police Actions) the Dutch were forced to accept the independence of Indonesia in 1949.

Media coverage and personal experiences during the ‘Bersiap Period’ by Dr. Nonja Peters

See also:

Evacuees from Netherlands East Indies recuperating in Australia after WWII

Migration and Repatriation issues after the liberation of NEI