The new doctor

There is a red book. It is one of many books in a series. This one is devoted to the letter ‘S’. There is nothing in it except surnames starting with ‘S’, and the history of these names. Because it is a Dutch book, the name ‘von Schmidt’ is in this book. The name has additional names which reflect the purchase of the town of Altenstadt in 1577 by the family, raised to the noble class by Emperor Rudolph and confirmed in that status by Emperor Charles VI in 1713. The family were recognised as nobility without title, denoted by the honorific Jonkheer, in the Netherlands in 1839.

Any list of Dutch names, regardless of the year in which such list is collated, is replete with names from a multitude of countries. A German name is no more out of place in a list of Dutch names as it is in a list of Australian names. This is a reflection of the history of the Netherlands and their policy of happily accepting refugees and traders and adventurers. In their turn, the von Schmidts, like so many Dutch people, did not limit their education or careers, let alone their marriages, to the Netherlands. Indonesia, Kent, Tiblisi, Oman, Mauritius, Guyana, Vancouver, Wales and other far flung places are embedded in the family story.

In Great Britain, especially after World War II, it was quite different. More so if your command of the English language, words, and sentence construction, pronounced with an alien accent, betrayed your foreign heritage. It did not help to claim Dutch origins – the German name proved the speaker to be of the wrong sort altogether. Punishment and humiliation needed to continue long after war had ceased, certainly amongst school boys who were cheated of displaying glorious deeds for their country and earning fame on the field of battle. An enemy in their midst was a gift. Protestations of innocence were taken as proof of guilt, their actions were justified.

So Freddie went to school every day, dutiful to the behest of his mum and dad, yet filled with trepidation. After years of bullying, and despite the efforts of parents, a big red-haired kid called Gregory stepped forward and became his protector. But the fear of being pushed to the ground and kicked at the capricious whim of any of his class mates never went away. Even in later years, the English disliked every part of the name Jonkheer Johan Karel Frederik von Schmidt auf Altenstadt, and Freddie found it useful to keep that part of him away from English ears.

Art, Movement and Mathematics, and later Geography, didn’t need a mastery of English language to excel in, but they were not the most useful subjects for an aspirant doctor to study. Yet when interviewed by a panel of career advisers, teachers and specialists of various sorts, he had one simple answer to the headmaster’s question. This answer was out of order, he was supposed to be serious. The ‘flippant answer’ was repeated earnestly, causing the headmaster to take him by the hand and lead him from the room with a ‘so sad we can’t help you, and you’ll never be a doctor’ remark.

The decision to become a doctor did not come out of the blue. The family has a longer memory than Freddie, and claim this was always his ambition. Freddie’s first memory is in the Broken Bones Clinic – bright and clean, ordered and purposeful, doctors and nurses in crisp white uniforms, firm and warm hands mending broken bones. This appealed to Freddie and was confirmed after another rough and tumble and another broken bone a few years later Freddie saw that to be a doctor was the best there could be, helping people to get better, and he wanted to do the same.

Freddie’s mother resolved, despite her limited means, to chart a pathway for his success. The family had moved to London in 1948 to gain the benefit of a small inheritance which was earmarked for the education of her three boys. Due to debilitating illness, his father could do little more than encourage him to persevere and excel. Schools were chosen, and subjects studied with a view on the prize. Working in laboratories, and as hospital orderly, even assisting in operating theatre work, fed his ambition and kept the wolf from the door. College grades were very good too, but the door to medical college remained elusive. For every 20 candidates, only one was chosen.

Frustrated and wondering if his ambition would ever be achieved, Freddie sought astrological advice. The £5 consultation fee generated an encouraging report excepting it was also frustratingly vague – he had been seen in a white coat across the ocean. All the part-time jobs he had done were in a white coat, and there were many places over the sea, so what did it mean?

Shortly after this, uncle Charles paid a visit. Sitting with his sister Margaret, discussion turned to the children and their possible futures. Reflecting on Freddie’s situation, it was suggested that it may be possible to achieve something in Australia. As Governor of West Australia (1951-1963), the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital had been named in his honour, and he was well aware of the opportunities there. Freddie was summoned, briefed and instructed to make contact with the West Australian Agent General in London.

Freddie was asked to demonstrate to the University of Western Australia that he had the qualifications that would make him eligible to be given a place in the medical school. On being found worthy he was given a place in a class of 156 students in Perth in 1967. It was a tough place to be – only the 32 best students would progress to the second year. End of year was especially tough – holiday jobs were important to earn sufficient money to get through the next year, all the while not knowing whether there would be another year of study.

More than 40 years later, we know the result – Freddie has been a doctor in our midst so long, he is now retired. Despite the years he still cannot refrain from bursting into a triumphant YIPPEE in relating the result of the first year exams, and the news that he qualified for a scholarship. The pathway to being doctor was cleared, and his mother was freed of money worry. With perseverance and an urge to excel, Freddie graduated shortly before his thirtieth birthday.

This was followed by six years of specialised study, of working in different places and situations, building experience, honing his skills. His West Australian certificate was highly regarded, and enabled him to gain positions wherever he applied, whether at King’s College or Scunthorpe, High Wycombe or Southhampton, Kalgoorlie and other places in between. Eventually he looked at being a GP in private practice. An abundance of doctors in West Australia limited his options but an invitation to a wedding in Hobart opened some possibilities. A time of being in demand as a locum allowed him to reflect and look for openings. The best option seemed to be in South Hobart, where he found a suitable building in Macquarie St., and hung his shingle on the 26th of November 1979.

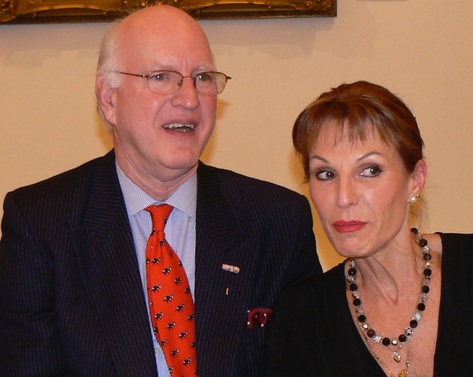

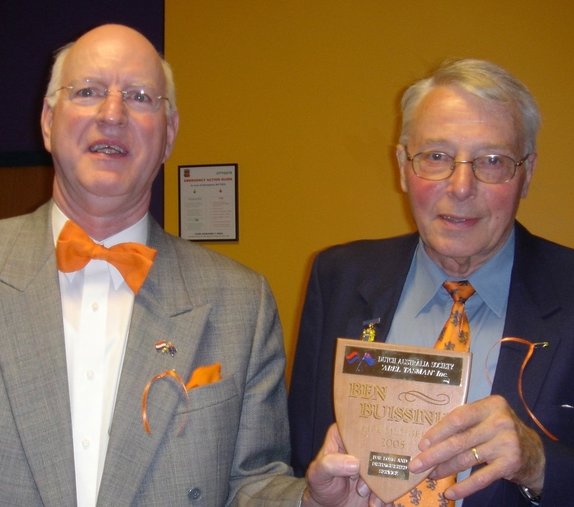

Over the years the practice thrived and Freddie became involved in community work. Through a series of events, not all of which were clear to him them, let alone now, he became the president of the Dutch Australian Society “Abel Tasman” Inc. in 1993, and held that position for twenty years. Both the Netherlands and Australia have no problem with any part of his name, and so he feels more at home in those places than he ever can in England.

Of all the other groups he became involved with, ‘Fine Dining’ has continued to hold his interest. His connections there resulted in a request to help Legacy with assessing pension eligibility, helping people to be as well as they can, a most practical and satisfying use of his skills through his golden years.

I recommend The Grid: The Fraying Wires Between Americans and Our Energy Future by Gretchen Bakke. It provides profound insights into the challenges of modernising energy infrastructure and remains highly relevant as the industry grapples with increasing complexity and renewable integration.

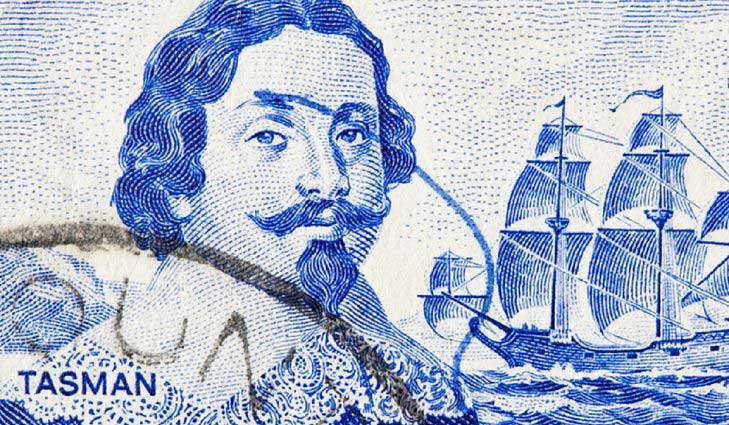

receiving a facsimile of Abel Tasman’s Journal from the Dutch Australian Society Abel Tasman Inc.

presented by Dr Freddie von Schmidt. 2005