The 25th wedding anniversary of Eric and Toni van der Laan was celebrated in 1954.

It was a major event in the Dutch migrant community in Kingston, Tasmania, fondly remembered 64 years later by those still alive.

In the shadow of the war years, and the major life upheaval of migration, it is truly a Job chapter 42 celebration.

A commentary on the program, with background and explanatory information, can be found below.

A translation of the program follows.

The end notes to the commentary, and a foto of the bridal couple, complete this page.

The Wedding Anniversary Job in Tasmania

Gerald’s face lit up when I showed him the program. Sixty-three years disappeared, and as he turned the pages, he began to sing all the songs. “That was the party,” he said, “that finished at five o’clock in the morning.”1

It was a party that once seemed a normal expectation and then seemed impossible. Twenty-five years earlier there was a vague knowledge that, all things being equal, this party would eventually happen. Life would be mostly good, the marriage would probably be blessed with children, and everyone would live happily ever after.

The children did come, closely followed by very dark days. At first, the presence and behaviour of the Nazi invader was quite benign, but they slowly became nasty. Impositions were made, each new demand harsher than the last. Food and consumables were rationed. Jews were forced at gunpoint to migrate to the East. Ex-soldiers were commanded to return to duty, possibly to be cannon fodder on the Eastern front. Young men were dragooned into work groups to labour in the factories of the Nazi war machine.2

Many people resisted the decrees by disappearing from view, although sometimes only for a short period. Pieter Laning hid on a small island in the wetlands near his city. He complained of being sodden several times from torrential downpours, and of being bored witless. In later years he would regard it as a garden of Eden, but after the season of razzias in Groningen ended he was happy to return home.3

The thousands of people who disappeared underground, literally and figuratively, all needed food which could only be obtained with appropriate documentation. People sympathetic to the plight of those underground, and actively involved in helping them survive, formed a loose association of resisters to the regime. The regime labelled them ‘terrorists’ and hunted for them. Resistance workers who had been caught were violently interrogated and deprived of food, comfort and medical assistance, if they were lucky.4

After the war, a small group of Resistance workers, men who had entrusted their lives to each other, resolved to begin a new life as far as they could from the terror, horror and blunder they had endured. They settled in Kingston in 1950 5, and four years later, they celebrated. The celebration was bigger than anything they had had so far – far bigger than the wedding of Wim to a glove representing his bride (in Holland) so that she would be protected by a wedding ring when she travelled to join him.6 It was also bigger than the wedding of two Dutch migrants in 1952. The Warden of Kingborough at that time was pleased to have this event recorded in the Council minutes, along with his hope that there would be many more.7 Many Kingston people were involved in that celebration, including the school master and the grocer, who thrived on the memory to the end of her days.8

But this wedding anniversary celebration was much bigger than anything before, because it was a celebration of life. Pieter Laning took on the organisation of the event. He was the most lively, inventive and energetic member, and also the prankster, in his cohort.9 Two years earlier he had complained of pain in his back every time he coughed. The diagnosis of TB forced almost a year’s medical treatment and bed rest, just when he was getting into his stride in his new country.10 He remembered the extreme pain and agony he had endured in the horror of the Bay of Lubeck bombing, where so many suffered all the torments of hell, a place beyond the screams of agony, where thousands abandoned all hope of living. Then he had been in the wrong place, with the end of life in sight. Now he was in the right place, as Tasmania led the Commonwealth in the control and treatment of TB, and an end to the illness was in sight.11

Pieter sent out invitations to the migrant community, and called for entertainment submissions.12 Choirs were formed and skits prepared, stage names were invented or imposed, songs were composed and rehearsed, a programme was devised and typed and printed. Gaps on the page were filled with line drawings by Pieter, or with the favourite proverbs of the guests, or advertisements – all invented by the self appointed Master of Ceremonies. He might have been laid low by illness but now he was on top of the world.

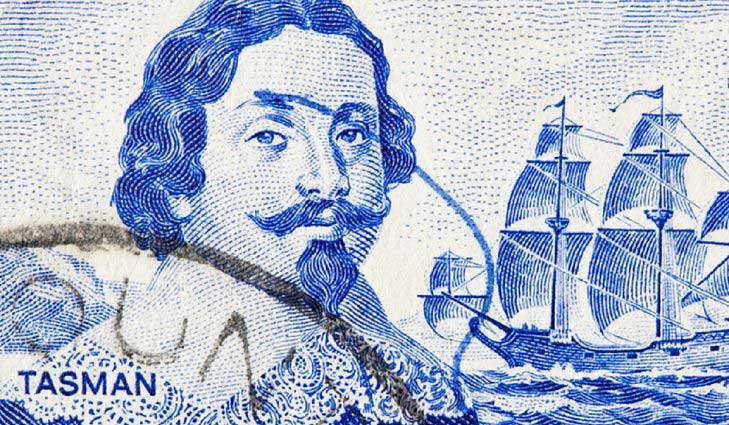

A photo of the happy couple, looking plump and content, standing in front of their new home, was fixed to every copy of the programme to celebrate the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of Eerke van der Laan and Toni Bandholz, at Kingston, 12 November, 1954. The American Gothic pose has been arranged by the photographer to minimise the difference in height of a couple sometimes called one and a half cents.13

Before the war, Eerke had been a champion gymnast, invited to compete in the 1924 Olympic games which he declined, because he refused to compete on Sundays.14 Towards the end of the war, he survived a forced march from the concentration camp to Lubeck Bay, where the witnesses of the Nazi atrocities were loaded on ships to be scuttled in the Baltic Sea. A blunder by the RAAF destroyed the ships in the harbour, and few survived.15 When Eerke finally dragged the forty-five remaining kilograms of his six foot frame back home, his family thought a bundle of rags had been abandoned on their doorstep.16

Eerke used his administration skills to achieve a lot. In Tasmania, he was equally happy to have builders tools in his hands, or to prepare a church service. Fluent in English and German since leaving school,17 he always ready to use his skills or to put his hand to whatever else was needed to help others. He was regarded as a leader by all, noted, inter alia, by The Mercury,18 but he preferred the privilege of service. Toni filled the role of rock, solid as the dolerite of a Tasmanian mountain, in their busy life.

At eight p.m., in Number Two workshop of the Australian Building Corporation (ABC) in Little Groningen, Kingston, the celebration began with a word and a prayer from their pastor, the Rev. Y van der Woude. This was immediately followed by all singing Psalm 103:1 “Now thank we all our God”. This was sung in Dutch, and the whole programme was conducted in Dutch, despite rule 10 in the programme insisting that it was compulsory for everybody to speak English that evening.

Only one verse of one song in the programme was composed in English, and printed with the notation ‘sing cheerfully and happy’. Somehow it was expected that the only local girl in their midst would be willing to sing about the Dutch boy she fancied, with words written by a person she sort of knew, in front of hundreds of Dutchies. Kingston people loved the Dutch migrants in their community and had established many strong personal links,19 the Kingborough Council preferred them above British migrants,20 and there was a shared vision for a more prosperous future together, but April was neither cheerful nor happy, just a super embarrassed teenager, and hid under the table when her turn came to declare her love in song.21

Rule 17 in the programme stipulated that the utmost respect needed to be shown to the Jenever Functionaries – an invented title for the persons in charge of dispensing alcoholic drinks. Their task, anticipating RSA courses and certificates by forty years, was bolstered by the many invented proverbs in the program that encouraged drinking in moderation. They could not know that their role would eventually be one shot of a broadside that could be fired against the doctoral assertion by Julian 22 that the group was teetotal. Smoking, on the other hand, was only frowned upon by evangelical and fundamentalist Christians.23 Cigarettes were placed in tumblers for guests to enjoy liberally, and the aroma of cigars was enjoyed by all.

One of the songs composed for the celebration related the highlights of the Dover High School job, set to a familiar Dutch tune about windmills. Another, written to fit a Saint Nicholas tune, ran to thirteen verses, each a little story about events in the life of the individual nominated to sing it. Some details were quite personal, speaking of far away love.

Item six on the programme gave the opportunity for speeches to be made in response to the two official speeches. It was noted that, should inspiration be lacking at this point, opportunity would be given after drinks. After several songs sung communally, Bart gave a graphic presentation. The painter in the Company, he had had time to hear and reflect as he wielded his brush. He had collected intelligence for the Allies during the war, so a light-hearted report on the gossip of the ABC was easy to do. He had been number one on the list of terrorists wanted by the Gestapo in Groningen,24 and was convinced that the Lord gave him the right words to say on the several occasions when they could have taken him. Now he carried a legacy of painful memories, as well as some hearing loss and nagging headaches, which he accepted just as the Apostle Paul accepted his torment.25 Otherwise he went on to live a long, full life, right up to the end.26

Bart’s piece was followed by a presentation of “The Model Commander” (loosely based on a Gilbert & Sullivan work), made in Dutch by three of the women. They also presented a skit about newborns which probably resonated well amongst the audience of mostly young families. The average age of the group was 37, because many were late starters. The war had put so many lives on hold, that three babies in five years was the new norm.27

Food was rarely mentioned in writings of the period, except when novel or exceptional. In the winter of 1950, Eerke and his best friend Ep had been nominated to be the “Joshua and Caleb” of the ABC group. They had first scouted northern Tasmania, and experienced a meat pie in Launceston – which they described as a pastry with a hot, but undefinable, filling. Nothing else in the north appealed to them either, and they were advised to seek their future south of Hobart.28

Blissfully unaware that there were only two buses from Hobart to Kingston each day, they missed the nine-thirty and started walking. Archie Smith came by, gave them a lift, gave them work, gave them connections to government, and gave them lunch – barbecued lamb chops that he especially went to the butcher for, and a can of green peas, cooked on a campfire on the building block. They described this meal as a banquet fit for a king, with power to transport their minds to beautiful places.29

The Australian ‘bring a plate’ concept which allowed an open invitation to an event and guaranteed there would be sufficient food was novel. The host was not responsible for providing sufficient food for all those who turned up. The quantity, quality and type of food that became available on the supper table could be anything. At this celebration the equivalent of ‘Grub’s up‘ was used to describe supper, without further description or comment – the food, whatever it was, was important. Food was fuel and ballast – abundance was it’s most important quality.

After supper, there were many other skits and presentations of which we know the name or the presenter, but nothing else. In some instances even that cannot be known because nicknames are used, such as Sik, Wik and Dik, or “The Dutch Flowers of Kingston”. In all, there were 14 presentations before the main event, a performance by a choir, formed for the occasion, that called themselves the “Bird Song Singers”.

The choir was introduced with bombast and fiction. The audience were told that the celebration committee had made a huge effort to obtain the services of the world famous conductor of the “Bird Song Singers of Kingston”, Mr. Cornelianos du Overeemos (in penguin suit with flapping wings), and he was prepared to give a performance tonight with his famous youth choir. They had just this last week finished a jubilant tour through Europe and the Scandinavian islands, it was said.

The choir was scheduled to perform eleven items, all with some attention to quality music and an over emphasis on generating laughs. The members of the choir were all given fantastic, nonsense names and impossible, nonsense talents. Nonsense was allowed to happen because that was part of enjoying life, of experiencing the gaps in the rules of life, of indulging in the complexity and joy of being. It was an expression of the joy of the liberation, of having the world at your feet, of the freedom available to the children of God, children who enjoyed their relationship with their Father, the Creator of everything including playing with nonsense.

The choir members included Little Luutje, who was actually quite a big man and would probably have earned the same moniker in the Australian vernacular. Geertje Mus was described as a hoarse tenor, but the reason for the description is lost in the mist of time. Young Schut, with his ever cheeky grin, sang heavy bass although he was a small man. Storming Joopie had storm in his name, so his moniker was a lazy play with words, and he sang alt. His wife was a well known musician and choir master. Little Wigger was the only son of the celebrating couple, twenty years old and by far the youngest in the group. The moniker was a little dig at his youth, a hint that his voice had not yet broken, so he must be a rising tenor. Tommy Moustache was described as a soprano bass. His Resistance name was Tom, and it stuck. Once a Registrar, he had destroyed many civil records so that people ceased to exist to the Gestapo, besides stealing ration coupons.30 He was always convinced that he was marked for assassination for his war work, and therefore carried a pistol in the small of his back until his dying day.31

Little Rieks was six feet tall and as strong as an ox, one of the men who had one plate of potatoes and a separate plate of vegetables with a small piece of meat, maybe a meatball, for dinner. Every harvest five one-hundredweight sacks of potatoes were tipped into a purpose-built holding bin in his pantry, to keep him fueled through the winter. He was listed as the whistler, and performed a solo. Driessy Murk was a challenge for the programme maker – Pieter couldn’t find a stage name for this man, who also sang soprano. Wimmy Sik was probably the sort of man who would sing if he thought he was alone – he was described as an open window singer. Jackie from the Dam was actually Jack and didn’t come from anywhere near a dam, but the word was in his name. He sang sometimes alt, sometimes bass. Picky Kroon completed the group and sang mezzo soprano. He had a bass voice and a well-earned reputation as a fastidious joiner.

The program also included items that involved audience participation and recitations, jokes and the like, performed by the gentlemen Steen, de Haan, Pinkster, van Betlehem, van Herweijnen, Mosterd and de Vries. The gentlemen Slot and Balkema were insufficiently organised to have their song printed, but they had promised, according to the programme, to sing a duet.

At five o’clock on Sunday morning, Murk’s Janny (there were several Janny’s) led the party in a closing song. The words are on page 33 of the program:

Goodnight, we’re going to bed

The day has been good

We celebrated with each other

The silver wedding feast

Together we close this day

‘T was a celebration that is seldom seen

So happy and free, so happy and free.

The translation is almost clumsy, but the lines do rhyme in the Dutch original. The words speak of being happy (blij) because they need to rhyme with free (vrij), but their lives were actually filled with joy. As the ABC they had been able to build new homes for themselves, with front doors that were never locked. As butcher, baker and candlestick maker, they had acquired building skills and built houses and schools for the people of Tasmania. They would go on to build the new era – service stations, public pools, and TV studios.32

The memory of being unhappy and of lacking freedom, of a time when their lives had been put on hold by the war, deprived of opportunity and growth, was not yet faded. They had put their lives in danger for the sake of strangers in response to the call of the Gospel. Some had suffered brutal treatment, deprived of food, warmth and medicine. Families had lived in fear of betrayal and discovery in a world where no one could be trusted. Families had worried due to lack of news about fathers and brothers sucked into the violent world of the Gestapo, of their brutal prisons, torture chambers and concentration camps.33

Today they had celebrated the restoration of their health and wealth, of their families and freedom. It was far more than a silver wedding anniversary, it was a celebration of life and it was greeting the future as children of God and as Australians, free to be. For the

moment, at least, they were a big family, supporting and nurturing each other, having fun and working together, exploring opportunities and growing. They were building their church on the Margate Road, and had begun planning to build a school for their children like the schools they had attended, where parents accepted the responsibility of teaching their children. They had been faithful, they continued to be faithful, and God had blessed them, as he had blessed Job.34

References are available in the pdf version of this document.