When he was 18 years old, Jan van Herweynen was asked by his father to travel to Tasmania, purchase a piece of land and begin building a house. Jan was accompanied by his cousin Bob Brinkman and the sister of his mother, Janny de Jonge. They left Schipol airport in Amsterdam on the fifth of February and arrived in Australia on the 12th of February, 1951.

It was specified that Jan travel to Penguin, where a former fellow church member, Jan Ketel, had settled twelve months earlier with his wife and daughter. Jan was also told to use Ketel as his mentor, because he had at least two handicaps – apart from his youth, he knew very little English. Besides, there was also no way to ring his father to consult. International phone calls were difficult to make, and cost £1 per minute, more than a day’s wage for skilled workers.

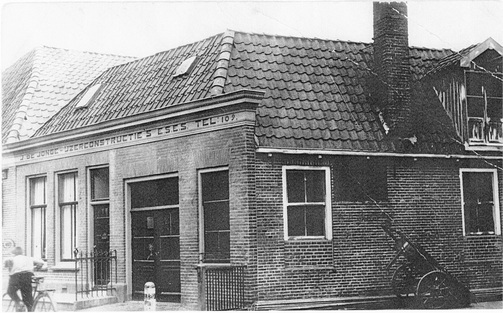

Father Herweynen thought that the family had better prospects in Tasmania. There was not enough work for all five boys in the family nursery, and Ketel had painted a picture of opportunities available in Tasmania. He therefore sold his half share of the nursery, and bought two prefab houses from Germany. This was to get around the restrictions of the Dutch government on the export of cash. He also borrowed money from his brother to help pay for the fares.

The rest of the family arrived eleven months later, also by plane, on the fifth of January 1952. They had left Schipol airport on the Flying Dutchman five days earlier. Peter clearly remembers that it was a very early start – 5 a.m. There was a lunch stop in Rome, where the family had their first ever experience of spaghetti – they needed instruction on how to eat it. The first night was spent in Damascus, in a hotel with armed guards. The most frightening stop was in Darwin, because immigration officials had managed, by accident or design, to separate the parents from the children, and the boys from the girls. Confusion bordering on panic reigned before they were all reunited after several hours.

It was not possible for the plane to fly on to Sydney without refuelling in Cloncurry. Here the family experienced the heat of the Australian outback in summer – a heat they had never imagined possible. It caused significant worry about the choice of country that had been made. Eventually the family arrived as scheduled at Wynyard airport at 5 p.m. on Saturday, where Ketel was waiting to take them to their new home, and the next morning picked them all up again to take them to church.

Because they were sponsored by Ketel, the family did not need to pass through any processing camps such as Bonegilla. Sponsorship meant that Ketel, in this instance, guaranteed that he had work and accommodation for the Herweynen family. They moved directly into their new home, as erected by Jan and his cousin Bob, with some help from Ketel. Peter suspects that because it was a prefab house that Jan probably didn’t bother with obtaining a building permit – Jan can’t remember.

The siblings of Jan were Jan Pieter, Cor, Johannes Bernardus and Lammert (aka Lammy) and Betty, Anne, Jenny and Liz. Nine children altogether – one of the few big Dutch families. There were not many big families, but Jan Pieter and his wife Elizabeth were already in their forties and finished having children. Most Dutch migrants were much younger, and if they were married and had children, only had one or two, as they had only just started.

Jan and Johannes B and father Jan Pieter were all called John by Australians, so father Herweynen became JP. Jan Pieter became Peter. The family was naturalised in 1958. Some had already dropped the “van” from the family name, Peter dropped the “van” in 1966 for simplification, some still retain it. When the children had children the Dutch naming convention of honouring grandparents by perpetuating their names was almost completely abandoned, and this has spared them and us a lot of confusion. Fifty years after arriving in Australia, the family tree would count 208 individuals as direct descendants of JP and Elizabeth or married to one of their offspring.

The third youngest of the children, Peter, once again became classmates with Ada Ketel and Annelies Rook. All three had started together in the same class in Steenwijkerwold, a village in the east of the Netherlands, but travelled at different times to Australia. Now, as young migrant children in Penguin, they were first placed in grade 1, and advanced as their English language skills improved. By the end of the year they were in grade 4, exactly where they should have been as ten year olds, and finished first, second and third in the class. It helped that they spoke very little Dutch at home. Dutch language skills simply had no value in their new environment.

In due course Peter moved on to the high school in Ulverstone. He has very vivid memories of a first for Tasmania – seeing and hearing a helicopter. Better yet, it landed on the high school oval. After one term at this school, the family decided to move to Kingston, as work prospects were significantly better there.

Peter was sent on ahead, so that his schooling wouldn’t be affected too much. He was able to board with his sister, Betty, who had married a Dutch migrant based in Kingston, Kemp Hetebrij. The daily commute to New Town High School continued even when the family caught up three months later, to a house they had bought in Kingston Beach.

Senior members of the family had formed a building company with another Dutch family in Penguin, the van Betlehems. Andy van Betlehem, his son Gerald, and Lammy all had trade qualifications. JP had, on arrival in Australia, recorded his occupation as “grower”. They named the business South Eastern Builders, with an eye to that area of Tasmania.

The van Betlehem family moved from Penguin first, in 1954. They used the Herweynen house in Kingston Beach for a few months, until they bought a property in Old Tinderbox Road in Kingston. They had arrived by ship two months later than the Herweynens, and the two fathers had worked well together establishing the Reformed Church of Penguin. The Kingston property had a very large shed, but the land was mostly bush and too large for the needs of the business or the family. A portion was subdivided and sold to the Association that built Calvin Christian School.

Peter Herweynen was taken on by South Eastern Builders (SEB) as an apprentice carpenter in February 1958. The following year the company moved their workshop to 169 Campbell Street in Hobart, where there was also room for a yard. An old house on the site had been converted to flats. It suited the company to let one of these flats to Peter in return for caretaking duties and it suited Peter to be happy with this arrangement.

The first job that Peter was involved with was the construction of the water pipeline from New Norfolk to Hobart, especially the formwork for the concrete pits that housed valves and other controls on the pipe. This job included some welding, for which training was insufficient. Besides, it was important to get the job done quickly. As a consequence, Peter almost lost his sight due to welding flash. An old timer advised him, when he was at the point where he could barely see, to coat his eyes, and keep them coated overnight, with a paste made from sugar and a little water. The treatment worked like a miracle.

The SEB took on some interesting jobs in the Hobart area, confident of their ability to use advanced building techniques despite their lack of experience, and Peter was involved with all of them. Jobs included the grandstand at KGV Football ground, the Zinc Co Casting Workshop, the Empress Towers (an exclusive apartment complex) and the Terminal for the Empress of Australia, a roll on-roll off ferry that plied between Hobart and Sydney. The terminal is now part of the CSIRO complex. The Empress Towers in Battery Point was, when built, the tallest building in Hobart, and the first constructed using the slip form method, which involved a continuous 24 hour concrete pour. Residents opposed to the project could not claim infringement or destruction of heritage values to stop the project, because heritage was little valued in those days, and so forecast doom and gloom for such an adventurous construction method, but have so far been proved wrong.

In 1961 Peter married Anneke van der Molen, and they lived in the Campbell Street flat for some years. The first two of their four children were born there, before bigger premises became necessary. They had planned a church wedding, but that became difficult when their minister suddenly resigned. The minister of the Launceston Reformed Church, Rev. Kramer, was willing to come down to Kingston to perform the church ceremony, but he was not a licensed celebrant. Thus the marriage ceremony was held in the Kingborough Council Chambers, in their best clothes, in the morning. In the afternoon the wedding service was conducted in the Reformed Church with the wedding party in all their finery. After this they all drove down to the Kingston Beach Hall for celebrations. It was a fine, dry and sunny midwinter day.

In his free time Peter played soccer with the Kingston Soccer Club, which folded in 1962, then with South Hobart until 1965, and finally with Dnipro until 1973. In that last year, he had gone one evening to buy fish and chips for the children’s dinner, because Anneke was away. Whilst crossing the road, he was struck by a car – fish and chips went one way, Peter went to hospital, and four hungry kids wondered where their parents were. The injuries to his neck and his knee from the accident spelled the end of his soccer career.

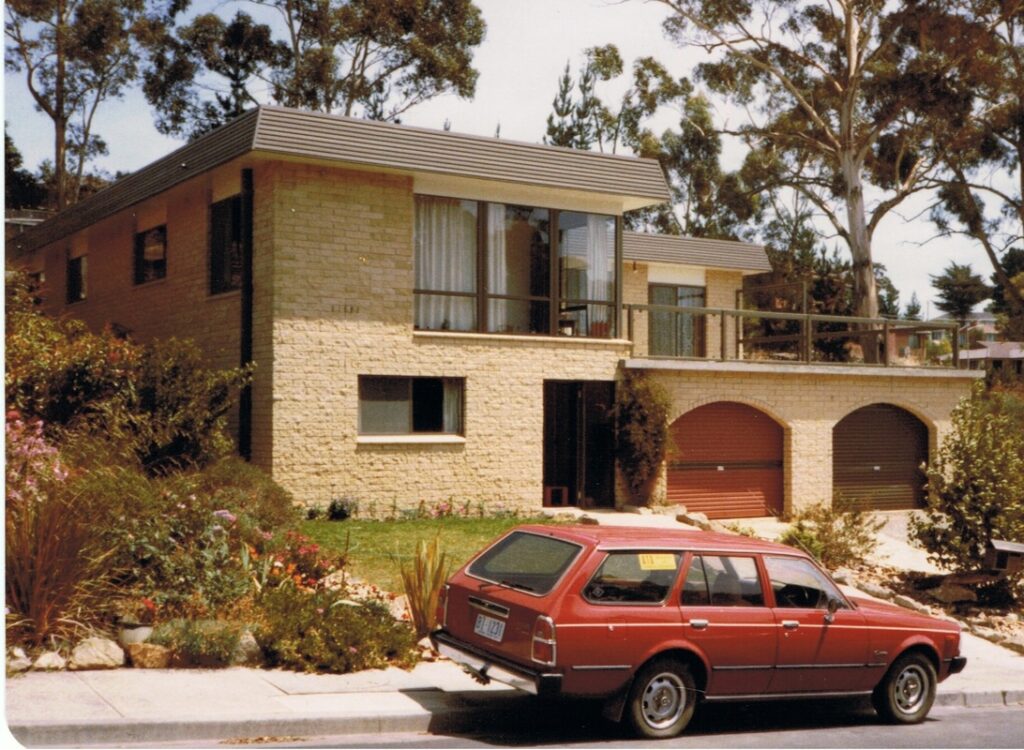

Free time was a rare commodity – there was always something to do in the time that was supposedly free. In the early years it meant putting in several Saturdays every year to erect the church building, and then to build the Calvin Christian School. Through the years there were more working bees – for maintenance or expansion of Calvin School, or for helping daughter schools and churches get their feet on the ground. It was not until 1977 that Peter began building a house for his family, and he chose a block not far from the school.

Work with the SEB continued until it folded in 1974 due to poor cash flow – credit was very tight and the government was as slow as everybody else in paying its bills. It took many years before everything was satisfactorily resolved. In the meantime both owners and employees had to find work elsewhere, and there was not a lot of work to be had. However, before the year was out Peter found a position with the Department of Housing and Construction, a federal government department. As structure supervisor, he was the person in between the engineers and the workers, because theory isn’t always easy to put into practice.

As the only structural supervisor for the department, Peter was involved in quite a few jobs, often concurrently. The first two were the new Hobart airport terminal and the Reserve Bank building in Macquarie Street. The airport job initially needed a lot of time, as it began just as the Tasman Bridge was partially destroyed by an errant freighter, and so a long detour to cross the river was necessary to be on the job. Eventually Peter kept a spare car on Bellerive Quay, and used the ferry to cross the Derwent.

Other jobs that Peter supervised included the Family Law Court and the Repatriation Hospital in Davey Street, the New Mail Exchange Building in Melville Street, the Cape Grim Anti-pollution Station, the Antarctic Division at Kingston, and the International Airport Terminal at Hobart for trans-Tasman flights to Christchurch.

In 1981 Peter was able to use this terminal as a passenger, flying via Christchurch to McMurdo Sound and on to Casey Station in Antarctica. Five years later he went to Mawson Station, this time via Perth, W.A., and then on the Nella Dan. The ship could not get any closer than 80 km because the ice was 2 meters thick, and so the last portion was by helicopter, another exciting air passage in his life.

Both Antarctic stations had major building projects in the 1980s to consolidate Australia’s claim to territory. Building in this environment needed a lot of planning and special techniques. Concrete was dry-mixed in Australia, and bagged. To use it as concrete, water had to be heated to 23˚C and added to the dry mix in a standard mixer, as typically used on domestic building lots all over Australia. Peter still claims the record for the largest single pour in the Antarctic – fifty cubic meters. It was an all hands on deck all day event, and the day was a long polar summer day.

The Antarctic building programme included a lot of supervising in Australia. Prefabs, for example, were constructed, and packaged, and the packaging needed as much time and quality of materials as the prefabs. The era was marked by a major learning curve of discovering suitability and practicality of materials for Antarctic conditions. Things that are taken for granted at home can behave quite differently in the harsh cold. For example, electrical extension cords became hard and brittle, and snapped when trodden on, creating a hazardous situation. Only rubber insulated cords would suffice, but they had to be hand made.

After the second expedition, in 1989, Peter took a retrenchment package, and a holiday in the Netherlands. He had been keen to go, and it seemed to be a matter of fact exercise. However, as he and Anneke approached his old village, emotions began, unexpectedly, to well inside. Memories, back to when he was four years old, of tasting chocolate and tobacco, compliments of Canadian troops camped nearby, came flooding back. Initially, he struggled to speak Dutch, as the words he once knew so well had become buried so deeply. When he went to buy cigarettes in the cafe, his old words and phrases came back. In renewing acquaintances, he discovered that the barkeeper was unhappy that the family had left, because he had lost his job as maintenance man as a result. Others noted that a large hole was left in the village when the family left, and this had caused some unhappiness. However, sufficient ill feeling was forgiven for Peter to score free drinks for several hours as he yarned with the locals.

The next two years were spent supervising the construction of the Centenary Building for the University of Tasmania. This was not an easy job, as the site presented some difficulties, especially a clay subsoil. After this job was completed, Peter applied for lots of jobs, but times had changed. He found that all his experience counted for nought – prospective employers gave preference to candidates with formal university qualifications. This did not make sense, he probably knew more with his hands and his eye than the graduates ever could with their books, but it was a new reality to which he had to submit.

In between job applications, he found some time to give to Youth With a Mission (YWAM) – an international Christian organisation which at that time needed someone to supervise a building project in Japan. He also spent some time working with his brother Lammy in Queensland.

On return to Tasmania, he teamed with his son Scott to do subcontract work for Boniwell Blinds, building sun rooms, carports, porches and the like. Scott was already doing this work, but there was plenty to share. When Boniwell wanted to focus on their core business, Peter and Scott formed Scope Home Improvements and continued with the home improvement side. They worked together for seven years, but business dried up during the credit squeeze of 2000, which coincided with the introduction of the GST. Discretionary spending collapsed as consumers came to terms with the new financial situation.

During the last years of his working life, Peter took on odd jobs wherever they could be found, including maintenance work on the properties of the Christian Homes for the Aged. To clear his debts he had to sell his home in 2002, despite the poor real estate market. This was the home he had built for his family, and it was a difficult time. He did, however, manage to keep a block of land, long held aside for his retirement. In 2009 he was given the opportunity to build two units on this parcel of land – the first was sold before it was completed, allowing the building of the second one in which he retired. As a builder he did, of course, build them himself. His low maintenance, well insulated home has plenty of space inside and a salubrious area outside for visits from the four children, seventeen grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

Many evenings are, or have been, over the past fifteen years, given as a committee member to meetings of various community groups, including the Dutch Australian Society (DAS) to foster and promote the heritage between Tasmania and the Netherlands, the Multicultural Council of Tasmania (MCoT) to assist migrants to Tasmania to settle here, and the International Wall of Friendship (IWoF) (as an elder) to celebrate the diverse heritage of all Tasmanians. When the children were growing up he was a soccer coach, and a member of the school board, and of school and church building and maintenance committees.

Peter especially noted that his achievements, and the time he has been able to give to community organisations, has been possible with two constants in his life. His wife Anneke has always been a homemaker, always at home for the family, and for this he is forever grateful. At a deeper level, Peter has been a member of a Christian Reformed Church (currently Kingston congregation) all of his life because he accepts Jesus Christ as his Saviour and Lord. Through the tough times this faith has been an anchor, at all times a guide.

During a recent holiday, Peter suffered a stroke. Recovery began sufficiently well for him to plan to return home. The day before this happened, Peter suffered a second stroke and moved to his eternal home.

4 October 1941 – 26 July 2016