Special Tasman’s Briefcase to mark the 300th anniversary of the death of Abel Tasman

The briefcase was made from black leather, embossed with the Tasmanian coat of arms. Inside there were several compartments.

The main compartment contained a carved {profile?] head of Tasman let into a block of Tasmanian myrtle.

A second compartment contained photos of Tasman memorials, and of the bay where the carpenter swam ashore to place the Dutch flag. This pocket also contained an address explaining the different objects in the briefcase and the object of the promotion.

Smaller compartments contained mineral samples from Mount Zeehan and Mt Heemskirk.

The Tasmanian Society presented the briefcase to the Dutch Ambassador Dr A.H.H. Lovink on the fourth of November, 1959, during his visit to Tasmania.

Source: The Mercury, 5/11/1959, p.7.

Tasman in the History of Tasmania.

In 1942 the world was at war, yet the three hundredth anniversary (tercentenary) of Tasman’s discoveries was celebrated, both in Tasmania and in Sydney.

The official activities included:

29 Nov 1942

Special service at Scots Church (St Andrews), Hobart.

3 Dec 1942

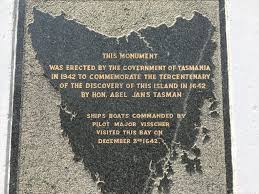

Unveiling, by His Excellency the Netherlands Minister (Baron F C van Aerssen Beyeren van Voshol MWO) of the Tasman Memorial, Dunalley. (photo above)

4 Dec 1942

Opening of a new wing at the Hobart Technical College and unveiling of a mural tablet inscribed “Abel J Tasman” as the future designation of the wing. Planting of trees at Princes Wharf.

5 Dec 1942

Tercentenary Royal Hobart Regatta Carnival, at which the Chief Commissioner for the Netherlands East Indies Commission unveiled a commemorative tablet (on the grandstand).

6 Dec 1942

Dedication at Campbell Town of an avenue of trees, and planting of three memorial trees by the Chief Commissioner for the Netherlands East Indies Commission, Dr J E van Hoogstraten.

7 Dec 1942

Unveiling of a tablet at the Public Buildings, St John St, Launceston, by His Excellency, the Governor.

In Sydney, two Italian prisoners of war recreated the map of the world as known to Tasman (including his discoveries). The map was a copy of an original in the floor of the New Church on the Dam in Amsterdam. It is in mosaic form in the floor of the Mitchell Library, Sydney (see image gallery).

In 1892 Some celebrations to mark the 250th anniversary. On this occasion a stone, with suitable inscription, was laid in the Church of England Cathedral (St David’s) on 12th January 1892. When the tower was constructed some years later, the stone was moved and can now be found facing Macquarie Street.

In 1838 The Royal Hobart Regatta was held for the first time. It was proposed by Sir John Franklin, partly to commemorate the anniversary of Tasman’s discovery.

The Journal of Abel Janszoon Tasman, 1642-3

Some Notes Concerning Tasman’s Journal

This article concerns an extract from the journal of Abel Janszoon Tasman, leader of an expedition sent to discover what lay south and east of Batavia. (M Bennett, The Impact of Europe 1640 – 1780, Selected Readings, University of Tasmania 2000 9th ed. pp 7-10). The extract describes some of the events on board his ships, the discovery of land, what they found and experienced there, all referenced by date. The document is an extract of an English translation of a copy of the original. The original was written by Tasman himself in Dutch, and a copy was made of this, either during the voyage itself or within the five months following [his return to Batavia. This copy is now in the State Archives (Rijksarchieven) in the Hague in the Netherlands and the original is no longer extant. (G Schilder, Australia Unveiled. The Share of the Dutch Navigators in the Discovery of Australia. Amsterdam, 1976, p140)

The introductory paragraph suggests this copy was written by Tasman, but is not in his handwriting. (G Schilder, p140) It is, however, signed by him to indicate that it is a true record of his journey. (FW Stapel, De Oostindische Compagnie en Australië, Amsterdam 1937, p83) Tasman wrote the original in a language that was not his mother tongue. It should also be noted that Tasman was first and foremost a practical seaman, not academically inclined. (FW Stapel, p68)

The translation of the document may, therefore, have some difficulties. The modern translator has to be competent in Frisian, aware that Tasman may have used words and phrases from his native tongue, (some Frisian words look the same as Dutch words but have different meanings – ‘kan net‘ means ‘cannot in Frisian and ‘can, but only just’ in Dutch) and in Dutch as it was spoken in the 17th century. To complicate the task, the handwriting of the copy is difficult to read. The small portion examined for this article shows two spelling errors, corrected by strikethroughs, in the first three lines. (the third word, translated to English as ‘description’ is written as ‘Beschrijng’ but should be Beschrijving. A different hand has inserted ‘vi’ with marks between the ‘n’ and the ‘j’ to indicate the correct spelling – the word ‘augustus’ (virtually the same) in English and Dutch, was first written as ‘augussus’ before a ‘t’ was written over the incorrect letter) Spelling errors are relatively easy to detect, if sought, but errors in transcribed numerals are less easily detected.

There is another copy of the original manuscript, known as the Huydecoper. Comparison of the two has shown, among others, variations in transcribing numerals. The extract now being examined also contains a transcribing variation, which completely reverses the meaning of the likely original. (line 6, p7, ‘distrusted’ should be ‘trusted’ – Heeres translates it as ‘not much to be depended on’).

The document is laid out in a fashion which infers that it was updated on a daily basis. This may or not be true, but the original document would be difficult to reconstruct from memory or invent at a later date because it is lengthy and detailed in many parts. Another document, reconstructed from memory nearly thirty years later, stands in stark contrast regarding details and length of account. (M Bennett, pp10-11). This is the document known as the Haalbos-Montanus account of the voyage of 1642-3. It is also easy to imagine, considering the pace of life during a voyage, and the division of labour, that there was sufficient opportunity to make the log up every day.

The current extract seems to give an account of daily, pertinent, occurrences on the expedition. However, many things which are of interest to the modern generation were not considered by the author and therefore not recorded. It is thus difficult for the modern reader to establish exactly what Tasman saw and where he saw it.

The document tells us nothing about the nature of the people involved, nor about their hopes and aspirations, nor about their skills except that one person, a carpenter, was a good swimmer. It tells us nothing of the ambience on board, how people got on with each other, or how their work was affected by this. It does hint that Tasman didn’t like wasting time. The extract refers to a meeting of the ship’s council on the 25th of November but nothing of their discussions and resolutions. It also omits nearly all details of location and weather conditions found in the translation of the original copy.

The extract does note, concerning observations made about native Tasmanians, “so they presumed here to be very tall people’ (M Bennett, p8) but omits the following clause ‘or must be in possession of some sort of artifice for getting up the said trees’. (JE Heeres, p29). This second clause suggests that Tasman was prepared to credit the natives with some intelligence, perhaps even enough for trade possibilities. When this clause is omitted, and Tasman’s subsequent actions considered, it suggests that Tasman was a bit frightened of meeting the natives.

The document is useful as an introduction to the general reader. Perhaps its major shortcoming is the lack of locational details, which makes it more difficult for the reader with an inkling of knowledge of the Tasmania coast of following the account. (J.B.Walker, Early Tasmania Papers,

(Tasmania 1902) pp128 – 132. Tasman named quite a few geographical features but these names are

generally not found in the journal and recourse must be made to maps to find them (although this may also be confusing without some explanation as the bay named Frederick Henry by Tasman is not the bay so currently known but is the bay now known as Blackman Bay).

For a clearer understanding of the event it is necessary to refer to the translation from whence this extract came. Ultimately, the copy in The Hague is the most important as it was composed most closely to the events being recorded. Without this manuscript we would only have the brief narrative of Haelbos, and a copy in the British Museum which seems to be a copy of the manuscript in the Rijksarchief, and an account by an unknown sailor from the Heemskerck. This sailors journal seems to have been written by an ordinary seaman with rudimentary handwriting and language skills, and is consistently one month out with the date. It is a fairly short account and seems to have been written well after the event.

by Dr F Von Schmidt, President, Dutch Australian Society, February 2005.

Additionally, there are several maps. None of these documents are as comprehensive as or as close to the source as the original copy. Finally, the cargo lists for the two vessels are still extant, and the instructions for the voyage, as issued by the Governor-General in Batavia. (G Schilder, p143ff). The main value of these documents is in comparing them, which helps a little in filling in some of the gaps, through additional detail or by deduction, in the original copy. The episode described in this extract is the first record of Europeans in this part of the world. (FW Stapel, p70)

Tasman notes he could not find anyone or anything to trade with or for. The facts of his discovery were duly noted and there was nothing more to do because it wasn’t worth doing. (G Blainey, The Tyranny of Distance, Melbourne, 1966, pp5-6)

K Wierenga

2000

Tasmania a Treasure Island

Tasmanians have long known that ours is an island of treasures, although not quite as tangible as the precious metals and valuable spices Abel Tasman came searching for almost four centuries ago. Commissioned by Anthony van Diemen, of the Dutch East India Company in Batavia, Tasman is credited with European discovery of Tasmania, New Zealand, Fiji and Tonga; he was the first to circumnavigate Australia. However, when gold, silver and spices were sought after, merchants and businessmen lacked the foresight to take advantage of the real treasures discovered and, like many a prophet, recognition came to Tasman belatedly. Luckily for Tasmania, the Dutch connection was re-established – albeit many years after his visit.

Post-war migration to Australia in the 1950s was fuelled by people searching for treasure – the treasure of safety and security, the precious chance to seek prosperity, the gold-mine of a haven where children could be raised in expectation of a settled, opportunity-rich future. Immigrants from many countries and with many different stories answered our country’s invitation to make their new home in Australia. The Netherlands, with its immediate experience of wartime occupation by a hostile foreign power, was among them. The children of those immigrants, secure now in the Land of Promise, would not realise until adulthood the sacrifices their parents made. But with the well-deserved reputation of the Dutch for balanced assimilation, their contribution to the building a young nation, and the acknowledged gifts that diverse cultures have brought, Australia has cause for gratitude to those who repeated Abel Tasman’s journey to the other end of the world.

Heritage, a sense of belonging and a background are treasures that many cherish as adults and work to preserve. In seeking their ‘roots’ many migrant children, and those born later, have returned to visit the homeland of their parents. For adults who have not enjoyed an extended family, who can’t remember ‘Uncle So-and-So’ whom they resemble, and who have only vague memories of where they lived as toddlers, such a visit is an emotional experience and a cultural revelation.

Betsy and Eilef Straatsma of Kingston travelled to the Netherlands, the country they left as small children, in 1996 in the company of four other couples of Dutch heritage and enjoyed their trip so much they planned another for 2003. By coincidence, they would be in Holland at the time the Dutch municipality of Grootegast was to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Tasman’s birth in the town of Lutjegast. (Abel Tasman had now long been a hero – and Grootegast and Kingborough now have ‘sister-city’ connections) Because of Tasman’s special connection with Tasmania, a delegation of Tasmanian citizens, through the Dutch-Australian Society, was invited to attend and the Straatsma’s were honoured and thrilled to accept.

A week followed of “wonderful hospitality, an absolutely fantastic time – the Dutch certainly know how to celebrate a special event! We felt so special,” said Betsy. Highlights included visits to the Abel Tasman Museum, a bike ride on the island of Schiermonnikoog, tours of farms and seaports and the amazingly modern Gasunie building, souvenir gifts and formal dinners. Dutch culinary treats remembered from childhood were enjoyed. “It had been a long time since I had eaten kaantjes and bruine bonen,” said Betsy.

Tasmania was also represented by Kingborough Council delegates and the winner of the Abel Tasman Art Prize, Sandi Rapson. This prize alternates between Tasmania and the Netherlands, the successful Tasmanian candidate winning a trip to the Netherlands. The week of festivities ended with a forty-kilometre walk for 4,000 people through the municipality of Grootegast.

At the Abel Tasman Memorial in Salamanca Place, and at the Channel Museum at Snug, Tasmania celebrated the anniversary of Tasman’s birth. From Grootegast, bricks from Abel Tasman’s cottage in Lutjegast were presented to the community by the Dutch Consul, and a celebration was held at the Hobart Town Hall. The Consul, Mr. George Huizing, said an exhibition of the story of the Dutch community in Tasmania would travel the State in 2004.

Gifts generously given, memories to build on, a heritage of friendship and happy cooperation – the Dutch-Tasmanian connection is certainly one to celebrate. Abel Tasman and Anthony van Diemen never knew of the real treasure they missed. Just one more reason for Tasmania to be called the Treasure Island!

Judy Redeker.

Abel Janszoon Tasman: our first local reporter?

Was Abel Janszoon Tasman our first local reporter? The journals written by this most important early European explorer 363 years ago did not exactly enjoy wide circulation at the time, but did have a belated effect on his eventual readership, for today one in every twenty Tasmanians has some Dutch background. However when Tasman left Batavia, dispatched by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, Antonio van Diemen, his mission was to search for new trade opportunities rather than a new homeland for Dutch emigrants. With two vessels, the Heemskerk and the Zeehaan, and 120 men he hoped to find riches such as gold, silver and spices. Almost inadvertently he discovered Tasmania, New Zealand, Tonga and Fiji and was the first European explorer to circumnavigate Australia. His links with Tasmania have been maintained, manifested not only in our large population of Dutch immigrants but almost certainly because of them.

Born in 1603 in Lutjegast in Kingborough’s sister-city municipality, Grootegast, Tasman was a keen sailor from an early age. In 2003, the 400th anniversary of Tasman’s birth, his hometown celebrated with exhibitions and a cultural festival for over 4,000 people. The seventeenth-century atmosphere of the Netherlands was recreated with food, music and seafaring nostalgia. Among official guests were representatives of Tasmania’s Dutch-Australian Society and local and state government, and the ambassadors of Australia and New Zealand. The inter-country bond is also fostered by an art competition held alternately in Grootegast and Kingborough annually, the prize a trip to the other of the two countries. From a small house in Lutjegast near the church, the house where Abel Tasman was born, two bricks were sent to Tasmania to be presented to the Lord Mayor of Hobart and the Channel Heritage Museum to commemorate Tasman’s birthday. Our connection is significant and well recognised.

As far back as 1842, Sir John Franklin proposed that a Regatta be held in Hobart to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Tasman’s discovery of Tasmania. In 1892, the 250th anniversary, a stone was laid at St. David’s Cathedral. In 1942, although the world was at war, the 300th anniversary was celebrated with church services, the unveiling of the Tasman Memorial at Dunalley, the opening of a Tasman wing of the Hobart Technical College, the planting of trees at Prince’s Wharf and Campbell Town and the unveiling of commemorative tablets at the Hobart Regatta grandstand and the St. John Street Public Buildings in Launceston.

Last Saturday Dr. Freddie von Schmidt of the Dutch-Australian Society Abel Tasman Inc. presented an Abel Tasman journal to Graeme von Bibra, president of the Channel Heritage Museum. “At $800 it was a bargain,” said Kees Wierenga, who has researched the document extensively. The original is no longer extant, but this copy – reputed to have been made by Tasman, but actually not in his handwriting – is signed by Tasman as a true record of his journey. “It is really two documents in one,” said Mr. Wierenga, “the original manuscript, which is a copy of Tasman’s actual journal, and an English translation of this.” This copy was made during the voyage or shortly afterwards.

Surprisingly, Dutch was not Tasman’s mother tongue. (He was a native of Friesland, a region of northern Holland.) His Dutch was that spoken in the 17th century, interspersed with the occasional word or phrase in Frisian, and the handwriting of the copier is difficult to read. A few errors in transcribing numerals, and some spelling errors, added to the difficulties faced by translators. The journal is a long, often detailed document written to serve its author and superiors, not readers of the 21st century. Tasman notes the most important – to him – discovery of his voyage: he could not find anyone to trade with, or anything to trade for!

Two misconceptions have arisen, perhaps due to difficulty in translating or mistakes in one of the few copies of Tasman’s journals. Tasman did not flee in cowardly fashion to New Zealand; strong northwesterly winds blew him from Tasmania’s east coast, and he was happy to travel with them as he had met no natives and not found the riches he sought. He was not fearful of ‘giant natives’ after seeing handholds ‘five feet apart’; allowing for ‘an Amsterdam foot’ measurement, the angle of viewing and perhaps a slight over-estimation, the separations were about average for an axeman at a chopping carnival! But don’t take hearsay for granted. See for yourself at the Channel Heritage Museum – the original, and in translation. Read All About It!!

Judy Redeker.

Thanks to Kees Wierenga, History Honours student, who generously shared information and research.

Art and Abel Tasman

A heritage of art and travel.

“I’m going to show you how well-raised we are in Lutjegast,” said Mark Kooistra at a reception in his honour as winner of the Abel Tasman Art Prize. Mark was expressing his thanks to the organising committee, obviously very happy to be in Tasmania and keen to do his home country, the Netherlands, his home-town, Lutjegast, and his family proud. But his comment raised a smile or two, especially from mothers who recognise the line: “Do your best. Make us proud. Show them how well you’ve been brought up!” Indeed, maybe even Abel Tasman’s mother farewelled her son thus as he set off to discover the great South Land in 1642. Lutjegast is the town in the municipality of Grootegast, Holland, where Abel Tasman was born, and 2009 was the first time the ATAP has been won by someone from this small town.

The Dutch connection.

With many Dutch Tasmanians having settled in Kingston in the early days of post-war migration to Australia, Kingborough and Grootegast have enjoyed a long-standing sister-city relationship. Those early migrants overcame many hardships, including homesickness, and made a place for themselves in their new country where their contribution has been enormous. At the same time, they’ve managed to maintain links to the old country and build a friendship between the old and the new that benefits both. While Abel Tasman was sailing south, nearly four centuries ago, some of his countrymen were back home creating a heritage of artworks in the Netherlands, artists the like of Vermeer and Rembrandt. Tasman’s epic voyage built for him a reputation as lasting and sound as those of the artists back home. Ten years ago the Abel Tasman Art Prize was conceived as a way of celebrating both the voyage to a new world, and the art of the old world the Dutch migrants left behind and the new one that welcomed them.

The competition.

The ATAP is a collaboration between the Dutch Australian Society, Kingborough Council and the Education Department. Every second year it offers the opportunity for a young Tasmanian artist to travel to Grootegast, fostering the links between Kingborough and Grootegast and gaining an appreciation of Dutch culture and the social and physical environment. And in alternate years, a young artist from Holland enjoys the reverse: a chance to travel to Kingborough, to learn about Australia, especially Tasmania, and to enjoy the best experiences our municipality has to offer in hospitality and sightseeing. Last year’s winner was Mark Kooistra. His winning entry features a raven observing aborigines by the light of fire, stars and moon. The aborigines are unaware of the threat European settlement brings to their lives, but at the same time the painting evokes a sense of exhilaration, of new and wonderful opportunities in a new land.

Working to criteria.

The Abel Tasman Art Prize is themed ‘Journeys’, highlighting Tasman’s epic voyage into the unknown and symbolic of the journeys, both physical and metaphorical, that ordinary people may experience during their lifetime. The competition is open to Year 11 and 12 students up to twenty years of age in southern Tasmania who are capable of travelling overseas independently. The artwork, which can be part of the student’s body of work for pre-tertiary assessment, must be accompanied by an artist’s statement of at least 250 words. Finalists are interviewed to determine communication skills, capacity to interact with people in the host country, the depth of awareness of historic and cultural links between the Netherlands and Tasmania and an ability to work to enhance these links. This year it’s Tasmania’s turn to choose a prizewinner. The deadline for registration is October 1st with work submitted in December, immediately following completion of College assessment.

Mark’s Kooistra’s programme.

Mark is hosted by two families while in Kingborough and many others are involved in making sure he has a good time. His activities include: air-walking, rock-climbing, mountain-bike riding; enjoying Mt Wellington, Salamanca Market, a cruise on the Derwent and the Bruny Island Cruise, courtesy of sponsor, Pennicott Wilderness Journeys; visiting local artists, galleries and museums and, of course, the Abel Tasman Monument. At his Welcome reception Mark did Lutjegast and his upbringing proud, and had lots to look forward to. His Farewell reception in August will be tinged with the sadness of leaving new friends, but full of memories of the trip of a lifetime for a seventeen-year old enjoying his first overseas trip. There’s no doubt he would recommend the competition to all young artists!

Judy Redeker

Visit www.kingborough.tas.gov.au – community and recreation. Ask your art teacher for a brochure. Or contact Kingborough Council on 62118200.