An often used trivia question in the Netherlands is, what part of the Netherlands remained unoccupied during WWII. The answer is Southwest Dutch New Guinea, with Merauke as its capital

KNIL Forces in Netherlands New Guinea at the time of the Japanese invasion

| Babo– Stadswacht section, KNIL militia company. Manokwari– KNIL militia company. (That is all) |

Source Allies in a Bind

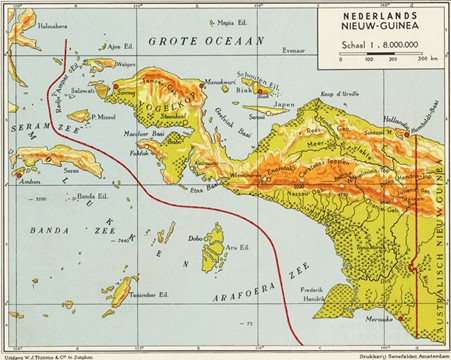

When General MacArthur initiated an offensive on mainland Netherlands New Guinea on a modest scale in 1942, his left flank faced a threat from the movement of the 5th and 48th Japanese Infantry Divisions, which shifted westward towards the Timor-Ambon area north of Darwin. One Japanese headquarters was situated near the town of Dobo on the Aroe (Aru) Islands. Examining the map reveals that the Aru Islands directly opposed the Merauke-Tanah Merah area, constituting a direct threat to Netherlands New Guinea’s security. Merauke emerged as the primary target. In response, 67 airfields were constructed in an arc on the north coast of mainland Australia. Although MacArthur’s Allied staff considered the possibility of invasion, contradictory intelligence on enemy objectives and movements did not impede MacArthur’s offensive plans. Despite military reinforcement in Merauke with infantry units of brigade size, the intelligence remained inconclusive.

While the Japanese never occupied Merauke, the town experienced frequent bombings, particularly in 1942 and 1943. The first Japanese air raid occurred on December 22, 1942, executed by aircraft from the 23rd Japanese Air Flotilla stationed at Kendari (Sulawesi) and Ambon. General MacArthur had additional plans, beyond the Netherlands New Guinea he saw this as a stepping stone to his planned Philippines offensive.

Furthermore occupying the islands in the Arafura Sea offered a springboard for advancing towards Sulawesi and Borneo. Lack of troops and equipment, along with the challenges of crossing the Timor and Arafura Seas and the Flores and Banda Seas, led to the abandonment of this latter plan. Nevertheless, an order to construct an airfield in Merauke for air defense against potential Japanese air force attacks was issued. In June 1943, American troops commenced the airfield construction, but the work ceased a few months later when these troops were urgently redirected elsewhere, notably Guadalcanal.

Merauke’s township was effectively razed by Japanese bombing, leaving scattered buildings and huts standing along sparse roads that either led into the jungle, swamp, or terminated at the beach near the Merauke River mouth. The river, characterized by yellow-colored water, meanders from the north, fed by the central mountain range’s waters. The surrounding mangrove forests create an impenetrable jungle, inhabited by millions of malaria mosquitoes, posing a perpetual challenge for the village residents. The inhabitants took atabrine tablets as a preventive measure against malaria, resulting in the distinctive yellow complexion of Merauke’s residents. To the north and east, the flat primeval forest transitions into rolling terrain, part of the high mountains’ spur with peaks such as Carstenz and Wilhelmina, reaching nearly 15,000 feet. These peaks, covered in eternal snow, are rarely visible, primarily in the morning hours before tropical rain fronts build up over the central mountain country, leading to heavy thunderstorms and rains—a characteristic natural phenomenon of New Guinea.

The defense of Merauke became a topic of discussion at the Advisory War Council meeting on January 25, 1943. The decision was made to complete the airfield construction as Japanese reinforcements in the Timuka-Kaukenau area indicated a significant interest in Merauke, evident in reconnaissance flights over the region. The completion of the airfield aimed to prevent the Japanese from utilizing the partially constructed airfield swiftly if they were to occupy Merauke, posing a threat to MacArthur’s New Guinea offensives.

Building a landing strip on the marshy coastal surface near Merauke for medium-weight aircraft proved challenging. The Americans opted to cover the runway with Perforated Steel Plates (PSP), resulting in a valuable runway extending into the alang-alang foothills (low bush). By the end of June 1943, the airfield was ready, and on June 30, the first plane landed.

Navigation options were scarce, with Merauke station being the only sounding station. P-40s faced difficulty maintaining contact with Radio Merauke during overland flights due to weak on-board transmission/reception equipment. Later, when Hollandia and Biak were captured, navigation possibilities increased, but there was still no overlap. Consequently, P-40s often flew between 800 to 1000 km without ground station contact. Given the P-40’s single-engine nature and the unreliability of its liquid-cooled Allison engine, the pilots of the 12oe encountered significant challenges even without facing the enemy. Briefings frequently reported the disappearance of American or Australian transport planes over the jungle. Fighter pilots with their single-engine aircraft faced a similar fate, knowing that getting lost or experiencing engine failure meant an emergency landing in the jungle, with little chance of survival. Additionally, the Papuan people were notorious for their aggression and headhunting practices.

Source: De Militaire Luchtvaart van het KNIL in de jaren 1942-1945 by O.G. Ward

See also: