Author: Michael Clyne

Introduction:

In this seminal article, sociolinguist Michael Clyne investigates the unique trajectory of Dutch language use and decline in Australia, comparing it with other community languages such as Italian, Greek, German, and Vietnamese. His central question: Is the Dutch linguistic experience in Australia an anomaly, or does it represent the endpoint of a broader pattern of language shift among immigrant groups?

Clyne frames Dutch within the broader context of Australia’s multilingual society, noting that by 1991 over 100 immigrant languages were in active use across the country. However, Dutch stands out for its extraordinarily rapid decline, despite early visibility and an educated, skilled immigrant base.

Key Themes and Findings:

1. Rapid Language Shift

Dutch Australians have experienced the highest rate of language shift to English of any major European community in Australia. In 1991, 57% of Dutch-born Australians spoke only English at home. In the second generation, the figures reached 88.7% (endogamous families) and 97.5% (exogamous families). These rates far exceed those of Greeks, Italians, or Poles.

2. Contributing Factors

- Cultural Proximity: Dutch culture and values are perceived as closer to Anglo-Australian norms, encouraging smoother integration and less pressure to maintain linguistic difference.

- High Exogamy Rates: Dutch Australians exhibit some of the highest intermarriage rates, reducing the chances of Dutch being the home language.

- Weak Language as Core Value: Unlike Italian or Greek communities, for the Dutch, language was not perceived as central to cultural identity. Values like gezelligheid (sociability) and family were prioritised instead.

3. Policy Context and Community Response

During the peak of Dutch immigration in the 1950s, Australia was still in its assimilationist phase. Dutch migrants were seen as ideal settlers — white, Protestant, skilled — and were encouraged to abandon their language quickly. Unlike other migrant groups, the Dutch largely complied. There was limited Dutch-language media or advocacy.

While the 1970s and 1980s saw a shift to multicultural policies, the Dutch community did not capitalise on these changes. There was little push for Dutch language teaching in schools, and by the 1990s, the number of students studying Dutch at matriculation level had dwindled to just 22 across the country. Dutch was also withdrawn from university curricula.

4. Linguistic Change and Attrition

Clyne examines how Dutch, as spoken in Australia, has:

- Borrowed heavily from English (e.g. gesponsord, relaxen)

- Adopted English syntactic structures and idioms

- Dropped grammatical gender and simplified plural endings

- Shifted from the Dutch Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) to English Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order

- Experienced code-switching within and across sentences, particularly among elderly bilinguals

These patterns are shared with other bilingual communities, but the Dutch experience is marked by earlier and faster adoption, reflecting limited intergenerational transmission.

5. Language Attrition in the Elderly

Clyne explores the phenomenon of older migrants reverting to their first language. While this occurs among some Dutch elders, particularly those with low English proficiency, it is not universal. He proposes a “critical threshold hypothesis” — only those who failed to develop solid English in middle age are likely to experience language attrition in later life.

6. Comparative Position and Future Outlook

Dutch in Australia represents the end-point of a continuum: a model of rapid language shift influenced by assimilationist policies, pragmatic values, and weak language attachment. Clyne notes this is in sharp contrast to Dutch in Brazil or Indonesia (where the language had prestige and was maintained longer) and to the tenacity of Afrikaans, a derivative of Dutch.

Despite signs of renewed symbolic loyalty to Dutch among some second-generation Australians, the community faces steep challenges in reversing the decline. Strategies such as language reactivation are possible for those with residual competence — but for many, full reacquisition would be required.

Conclusion:

Michael Clyne concludes that Dutch Australians are not “intrinsically different,” but their community simply progressed more rapidly along a path that most immigrant groups eventually follow: the erosion of the heritage language by the second or third generation. What distinguishes them is how little they resisted this shift, how early it happened, and how fully it aligned with national assimilation policies.

His broader message is one of cultural reflection. In an era of multicultural recognition, the Dutch community — and others — should reconsider the value of linguistic diversity, not only for cultural retention but also for economic and geopolitical engagement, especially with Europe. Australia’s multilingual potential, he argues, remains an underused national resource.

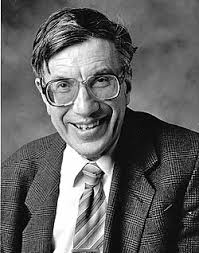

Author Profile: Michael Clyne

Name: Professor Michael Clyne (1939–2010)

Fields: Sociolinguistics, Bilingualism, Community Languages

Affiliations: University of Melbourne; Monash University; Australian Academy of the Humanities

Background:

Michael Clyne was one of Australia’s foremost linguists, a pioneer in the fields of bilingualism, language contact, and language policy. Born in Melbourne to German-Jewish parents who fled the Nazis, Clyne grew up in a multilingual household, which profoundly shaped his scholarly interests. His work focused on how languages function in contact settings, especially within multicultural Australia.

Contributions:

- Authored foundational texts, including Community Languages: The Australian Experience (1991), Dynamics of Language Contact (2003), and Pluricentric Languages (1992).

- Advised Australian governments on multilingual policy and education

- Was a strong advocate for language rights, language maintenance, and intercultural understanding

- His longitudinal studies on language attrition, especially among European migrant groups like the Dutch and Germans, remain landmark contributions

Relevance to Dutch-Australian Studies:

Clyne’s work on Dutch-English bilinguals is unmatched in its depth and detail. He was the first to systematically document how language, identity, policy, and pragmatism intersect in the Dutch-Australian context. His analyses revealed both the rich complexity and the quiet retreat of Dutch as a community language, situating it within the larger story of post-war migration and cultural negotiation in Australia.