This article is based on detailed historical notes generously provided by the Drijver family, who have preserved accounts shared privately by Robbie (Rob) Drijver in the final years of his life after the expiry of his wartime secrecy obligations.

The history of Dutch Australians during the Second World War contains many remarkable episodes, but few are as extraordinary as the life of Robbie (Rob) Drijver. Born in the Dutch East Indies, stranded by war, captured, rescued and recruited twice by Australian and American forces, his story spans continents and battlefields. For more than fifty years, he was prohibited from telling it. Only shortly before his death in 2005 did the military release him from his oath of silence.

This is the first attempt to reconstruct his life using family accounts, surviving documentation, and wartime context. It stands as a remarkable example of Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation at the most personal level.

Early life in the Dutch East Indies

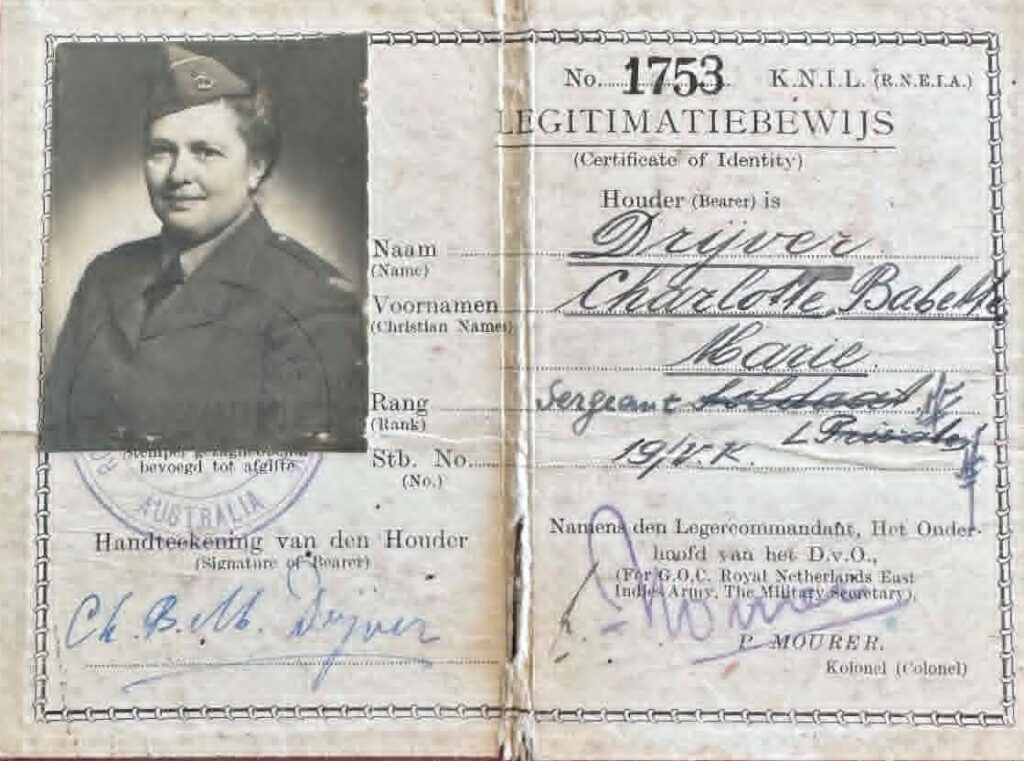

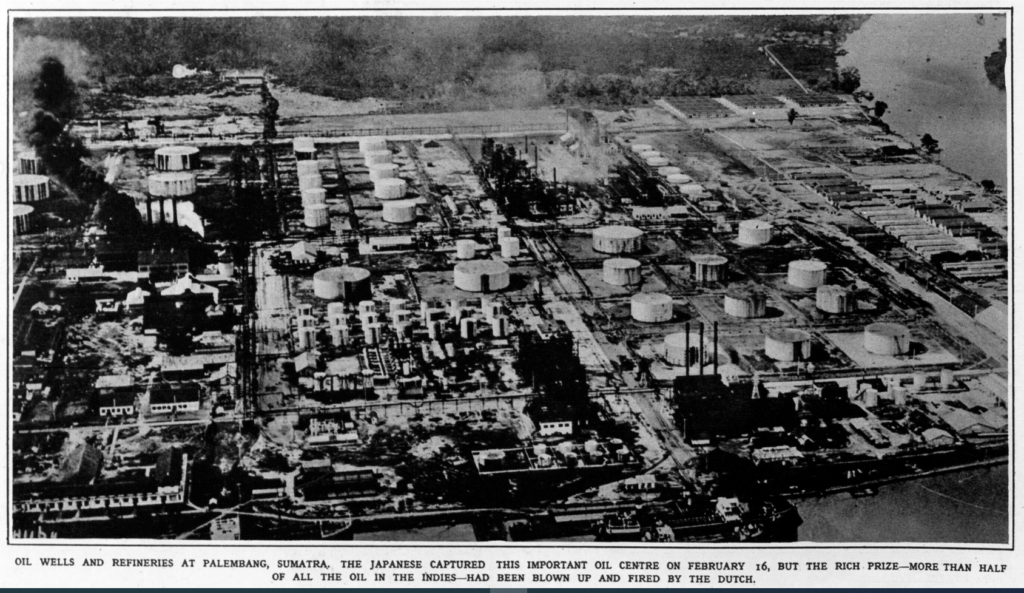

Robbie Drijver was born in Soerabaya (Surabaya), Java, to Martinus Jan Drijver and Charlotte Babette Marie (Lotte) Drijver, née Goedekemeyer, born 1903 in Medan. His father had served in the Dutch Submarine Service before joining the Standard Vacuum Oil tanker fleet based at Soengi Gerong (modern Sangaigerong) near Palembang in south-west Sumatra. The refinery complex at Soengi Gerong was one of the largest in Asia, located sixty-three miles inland along the jungle-lined Musi River.

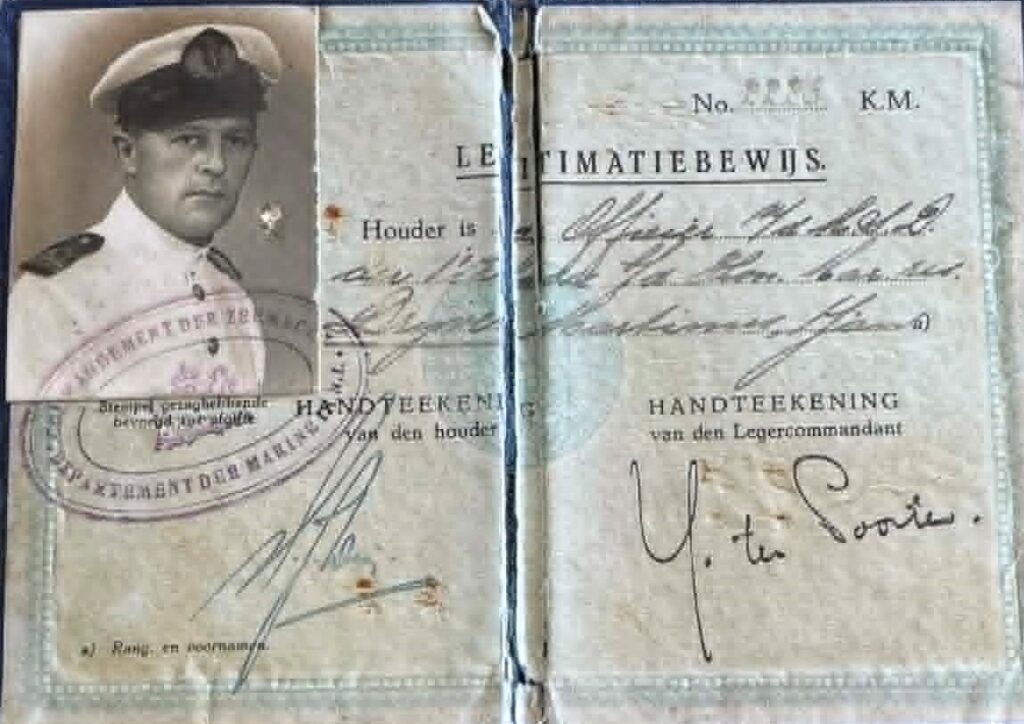

The pictures below are from Rob’s father and mother.

Rob grew up with two half-brothers, Eduard and Ben van Dugteren, Lotte’s sons from a previous marriage. Both were later taken prisoner by the Japanese at Singapore and interned in Changi.

His early years in Sumatra were marked by adventurous episodes that would later form the foundation of his survival skills. The family kept three Sumatran tiger cub as her mother had to shoot its mum as she has eaten the gardener, later the groen tigers were transferred to the Batavia Zoo. The boys were allowed into the enclosure to wrestle with the animal, much to the horror of onlookers. The family still has the tiger’s tooth that the natives insisted she must wear as protection after killing the tiger, she had it set in gold on a chain.

Rob joined in catching a crocodile trapped in a drainpipe for delivery to a zoo, and helped carry a large python that had swallowed a pig and become trapped. On one occasion he accidentally fired a rifle shot through a tree, narrowly missing his step-brother Eduard.

Separation and escape, January–February 1942

In January 1942, as Japanese forces advanced through the Netherlands East Indies, confusion reigned among the civilian population. When Japanese paratroopers landed at Palembang on 13 February 1942, Rob, then about fourteen years old, was mistakenly left behind, each parent assuming he was with the other.

He survived by living for a short period in nearby jungle villages with local friends. Soon after, he attempted escape by boat to Singapore, successfully locating a Chinese ship’s chandler who knew and respected his father. Rob had visited Singapore before with his father, so he was able to find refuge with the chandler’s extended family.

On 14 February, Japanese soldiers massacred staff and patients at the Singapore Alexandra Hospital. The city fell the following day. Rob was rounded up and placed in what appears to have been the civilian section of the Changi internment complex, in the women’s and children’s area separate from the male POWs.

The Chinese chandler organised an escape for Rob and several others. Although their sampan was fired upon by Japanese forces, they reached open water. A submarine surfaced next to them; to their relief it was American. Rob, who spoke no English, was taken aboard. He later recalled carrying a gun and knife, presumably returned to him by his Chinese protector.

Evacuation to Australia by submarine and Catalina

By early March 1942, U.S. Navy Patrol Wing 10 was evacuating its remaining PBY Catalina flying boats from Java to Australia. Records show that on 1 March five aircraft departed the Tjilatjap naval base on Java’s south coast: 101-P-13, 102-P-26, 101-P-3, 102-P-25 and 22-P-12 of VP-101. Family accounts suggest that Rob was transferred by submarine to either Tjilatjap or Soerabaya and placed on one of these Catalinas.

He arrived in Darwin during a period of intense military alert, less than two weeks after the Japanese bombing of the city on 19 February. Three U.S. PBYs of Patrol Wing 10 had been destroyed in the harbour during the attack.

Shortly afterwards, the Red Cross traced Rob’s parents to Melbourne, where he was transported for reunion.

Arrival in Melbourne

On arrival at their hotel, the concierge attempted to remove the gun and knife that Rob refused to part with; he wrestled the man to the floor. His mother greeted him with a slap, overwhelmed by the shock and relief of the ordeal.

National Archives of Australia records confirm an arrival: “DRIJVER Robbie – Nationality: Dutch – Arrived Melbourne per Jagersfontein 5 March 1942.” The Jagersfontein was a 10,077-ton Dutch liner that evacuated civilians from Tjilatjap on 27 February 1942. Only thirteen of the twenty-four ships in that evacuation convoy reached safety. It is possible Rob travelled from Darwin to Melbourne aboard this ship.

He was placed as a boarder at Scotch College, Melbourne, supported by a refugee assistance fund.

Involvement with Allied plans against the Sumatran refineries

Because Martinus Drijver knew the South Sumatra refinery region intimately, he became involved in discussions between Australian and American planners about possible operations to recapture or sabotage the oilfields. These facilities, at Pladjoe (Shell) and Soengi Gerong (Standard Vacuum), near Palembang were vital to the Japanese war effort.

Rob, as the person with the most detailed first-hand knowledge of the surrounding villages, waterways and rice-field layouts, was brought into a briefing where senior officers, including General Douglas MacArthur, were studying maps. MacArthur established his US Army headquarters in Melbourne on 23 March 1942, at 401 Collins Street, before relocating to Brisbane in July. This confirms that Rob’s meeting fell within the correct timeframe.

He identified a flaw in the proposed paratrooper drop zone: what planners assumed were small buildings were actually fish ponds, which would cause serious casualties. The drop zone was altered accordingly.

First commando operation, Sumatra

Soon after, Rob was approached again. A small Australian–American reconnaissance team was to be sent into the refinery region to verify the new drop zone and gather intelligence. Despite being only fourteen, Rob was selected for his local knowledge, language skills and jungle survival experience.

He underwent training in silent killing techniques at RAAF Point Cook, south-west of Melbourne. Approximately four men were dropped by parachute at extremely low altitude onto Sumatra.

Their tasks included capturing a Japanese soldier for interrogation. The first took his own life; a second hid in a hollow log and was extracted only after the team obtained a saw and frightened him out. The team identified the correct drop site but were detected during a skirmish in which Rob was injured by a grenade. He was evacuated back to Melbourne.

Second commando operation, Balikpapan, Borneo

Around two years later, now aged about seventeen, Rob was recruited again. This time the target was the oil-refining and port city of Balikpapan, Borneo.

This aligns with the timeline of the Allied landings on 1 July 1945, when Australian troops, supported by U.S. naval forces, assaulted the Japanese positions in one of the last major amphibious operations of the Pacific War.

Rob’s small detachment was tasked with clearing enemy guards from long piers extending offshore. Piers were guarded at intervals by pairs of Japanese soldiers. Rob, a strong swimmer, likely approached from the water. Family accounts say the team silently removed the guards one by one.

U.S. Navy underwater demolition teams were simultaneously working on destroying three rows of offshore obstacles. Errors in signalling by a British ship reportedly alerted Japanese positions prematurely, leading to heavier casualties during the landings than might otherwise have occurred. Rob believed many lives were lost as a result.

Post-war secrecy and recovery

Returning to Melbourne, Rob was ordered never to contact his commando comrades and was sworn to secrecy. Each Saturday an army representative visited him for what would now be called trauma or anger-management sessions. Concerned that his reflexes might remain conditioned to lethal responses, he was instructed to remove himself immediately from any confrontation.

In civilian life, Rob became a strong swimmer and athlete. By chance, his new swimming coach was Alan Crawford, one of the commandos who had served with him. They reported this contact to military authorities, who deemed it acceptable if handled carefully. Crawford had himself served in the 2/3 Independent Company (later 2/3 Commando Squadron, 2/7 Cavalry Commando Regiment), formed in 1941 and trained at Tidal River, Wilson’s Promontory. He later became a respected Melbourne teacher and headmaster.

Rob and Alan resumed a cautious friendship through swimming. Family accounts suggest Rob may have trained towards the 1950 Auckland Commonwealth Games, although this is unconfirmed.

Later life and release from secrecy

Around five years before his death in 2005, Rob was contacted by the military and informed that the 50-year secrecy agreement had expired; he was free to speak. He never publicly published a full account, but shared parts of his story privately.

Even late in life, his wartime reflexes were sharp. When a would-be robber threatened staff at the family’s store, Rob pinned the man under a chair and held him until police arrived.

He remained close to his family: his daughter Sally Carson lives in Sydney; his wife June lives in Young, New South Wales; and his step-brother Eduard resides in Rotterdam.

Legacy

Robbie Drijver’s story is an extraordinary example of a young Dutch evacuee whose personal skills, resilience and local knowledge of the Netherlands East Indies made him invaluable to Australian and American military operations. His experiences highlight a lesser-known dimension of Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation: the integration of Dutch civilians and refugees into Allied planning and reconnaissance missions.

His life also reflects the dislocation experienced by thousands of Dutch families who fled the collapse of the NEI and found themselves rebuilding their lives in Australia.

Although much of his operational record remains sealed or undocumented, the consistency of family testimony, supported by contextual wartime movements of units, ships and aircraft, makes clear that Rob played an extraordinary role in two critical Allied operations.

As more archival material becomes available, the Dutch Australian Cultural Centre hopes that the full extent of his contribution can one day be confirmed.