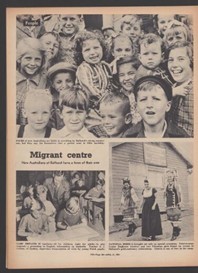

A Dutch-Australian gateway to post-war settlement

Between 1948 and 1952, the former army camp at Kelso near Bathurst operated as one of Australia’s largest migrant reception and training centres. Originally constructed during the Second World War for military purposes, the site was repurposed to receive European migrants arriving under Australia’s post-war population and labour programs. During its brief civilian life, the Bathurst Migrant Camp processed close to 100,000 migrants, making it a crucial but often overlooked gateway in Australia’s migration history.

For many Dutch migrants, Bathurst was their first direct encounter with Australia. After long sea voyages to Sydney, families and individuals were transported by overnight train to Kelso, arriving in a cold inland environment very different from the Netherlands. What awaited them was basic accommodation in former army huts: unlined iron and timber buildings that were cold in winter, hot in summer, and offered little privacy.

Dutch migration in context

The Netherlands emerged from the Second World War with severe housing shortages, economic disruption and limited employment prospects. For many Dutch families, emigration offered a way forward. Assisted passage schemes and later bilateral migration agreements encouraged migration to Australia, where labour was urgently needed in agriculture, manufacturing, construction and infrastructure.

Dutch migrants arriving at Bathurst were part of this broader movement. While official records often list them only as numbers, personal accounts reveal the lived reality behind the statistics: uncertainty, resilience, adaptation and gradual settlement.

Living conditions and daily life

Bathurst was designed as a temporary stopover rather than a place of long-term settlement. Most migrants stayed only weeks or a few months before being sent on to employment locations elsewhere in New South Wales or interstate. Nevertheless, the camp functioned as a self-contained township, with communal kitchens, ablution blocks, a hospital, classrooms and recreational spaces.

English language classes formed a central part of daily life, reflecting the assimilation policies of the period. Migrants were encouraged to learn basic English and to adapt quickly to Australian social norms. While cultural expression existed within the camp, official policy discouraged the long-term maintenance of language and customs.

Despite the difficult conditions, migrants created social networks and mutual support systems. For Dutch families in particular, shared language and experiences helped ease the transition, even as they were expected to “blend in” to Australian society.

Dutch personal experiences: Hanny and Baukje

Two Dutch women whose migration journeys passed through Bathurst — Hanny van der Mark and Baukje den Exter — offer complementary perspectives on life at the camp and the broader Dutch migrant experience.

Hanny arrived as a young migrant with her family in the early 1950s. Her account highlights the uncertainty faced by Dutch families on arrival: qualifications assessed overseas were not always recognised in Australia, housing was scarce, and families with children often struggled to secure private accommodation once they left the camp. Bathurst was a place of waiting and adjustment, where expectations met the realities of post-war Australia.

Baukje den Exter arrived at Bathurst in 1951 with her husband and four young children after a long journey from the Netherlands. Her recollections describe the physical hardship of arrival: lining up in the cold to be allocated a hut, collecting mattresses and basic household items, and learning how the camp operated. Illness, separation and strict institutional routines added emotional strain to an already demanding situation.

Together, their stories illustrate different aspects of the same experience. Bathurst was not remembered as a place of comfort, but it was a critical threshold — the point at which migration shifted from an abstract decision to a lived reality.

Moving on from Bathurst

For most Dutch migrants, Bathurst was only the beginning. Families and individuals were soon dispersed across New South Wales and beyond, sent to orchards, farms, factories, construction sites and industrial centres. Over time, many built homes, raised families, established businesses and became active members of their local communities.

While official policy emphasised assimilation, Dutch migrants often maintained informal cultural ties that later developed into clubs, churches and community organisations. These networks played an important role in supporting later arrivals and preserving Dutch-Australian heritage.

Legacy

The Bathurst Migrant Camp closed in April 1952, as migrant reception increasingly shifted to larger facilities closer to Sydney, particularly Villawood. Today, little physical evidence remains of the camp, but its legacy endures through the lives and contributions of those who passed through it.

For the Dutch-Australian community, Bathurst represents a shared point of arrival — a place remembered for hardship, resilience and transition. Personal stories such as those of Hanny van der Mark and Baukje den Exter ensure that this chapter of migration history is preserved not just as policy or infrastructure, but as lived experience.

See also: Bathurst Migration Camp