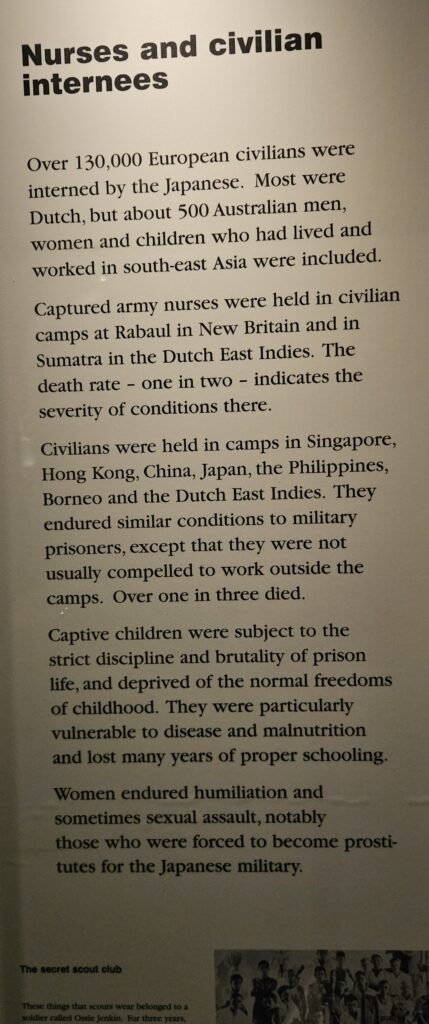

The physical environment of a Japanese prisoner camp serves as more than mere confinement; it becomes a stage for survival and adaptation. Whether situated in remote jungles, barren deserts, or urban centers, each camp presents its own set of challenges and opportunities. Natural features like harsh climates, rugged terrain, and limited resources impose physical hardships on detainees, testing their resilience and resourcefulness. Meanwhile, man-made structures such as barracks, guard towers, and barbed wire fences symbolise the stark reality of captivity and confinement. Understanding the interplay between the natural elements and constructed infrastructure sheds light on the daily struggles and strategies employed by both prisoners and their captors.

Social dynamics within Japanese prisoner camps are characterised by power dynamics, hierarchy, and survival strategies. Detainees form alliances based on shared identities, nationality, or language, providing mutual support and protection in the face of adversity. However, intergroup conflicts, fuelled by cultural differences or competition for scarce resources, often arise and escalate tensions within the camp community. Meanwhile, camp authorities exert control through surveillance, discipline, and manipulation, perpetuating a sense of fear and uncertainty among the incarcerated population. Exploring the complexities of social interaction within these camps unveils the mechanisms of resistance, collaboration, and adaptation in the face of oppression.

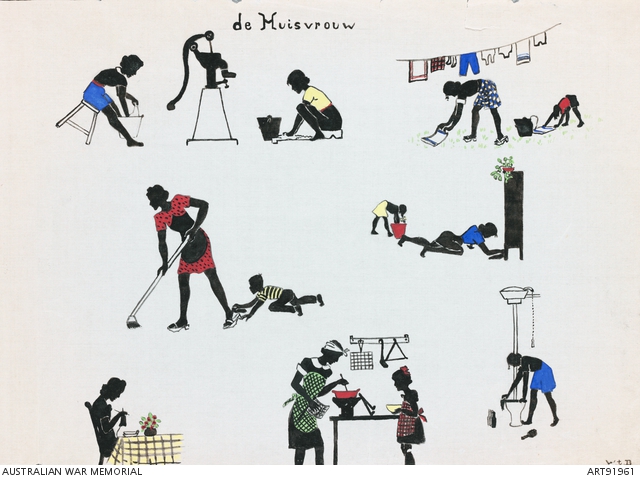

The psychological impact of internment extends beyond the physical confines of the camp, affecting the mental well-being and resilience of detainees. Coping with the trauma of captivity, loss of autonomy, and separation from loved ones, prisoners navigate a range of emotions, from fear and despair to resilience and defiance. Survival mechanisms, such as humour, camaraderie, and cultural rituals, serve as coping strategies, fostering a sense of solidarity and collective identity among detainees. Yet, psychological distress, manifested in anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, remains prevalent among survivors long after liberation. Understanding the psychological toll of internment sheds light on the long-term effects of trauma and resilience in the face of adversity.

See also: Jappenkampen in Nederlands Indie (in Dutch)

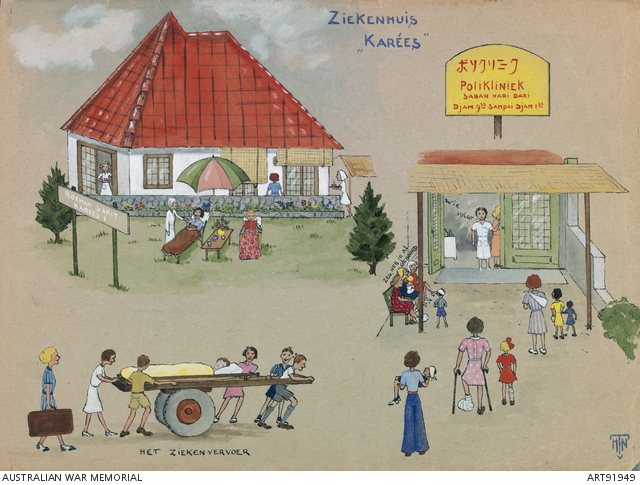

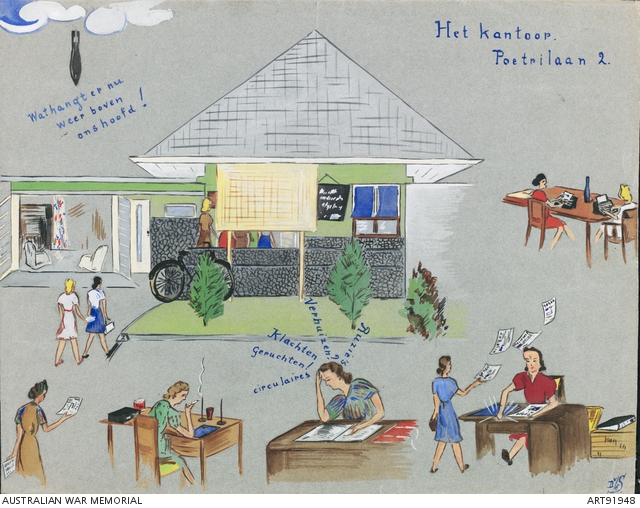

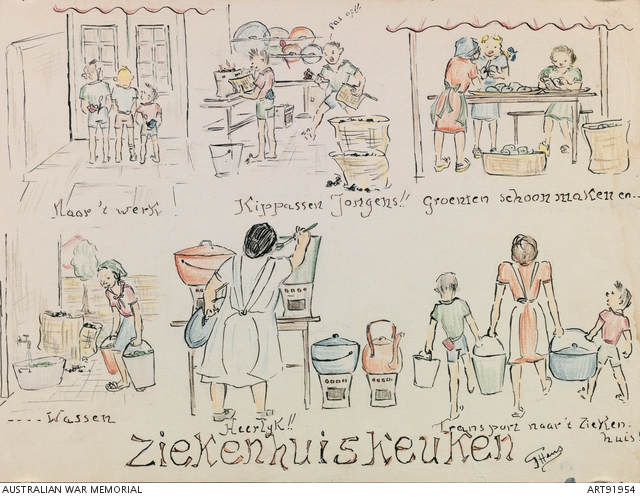

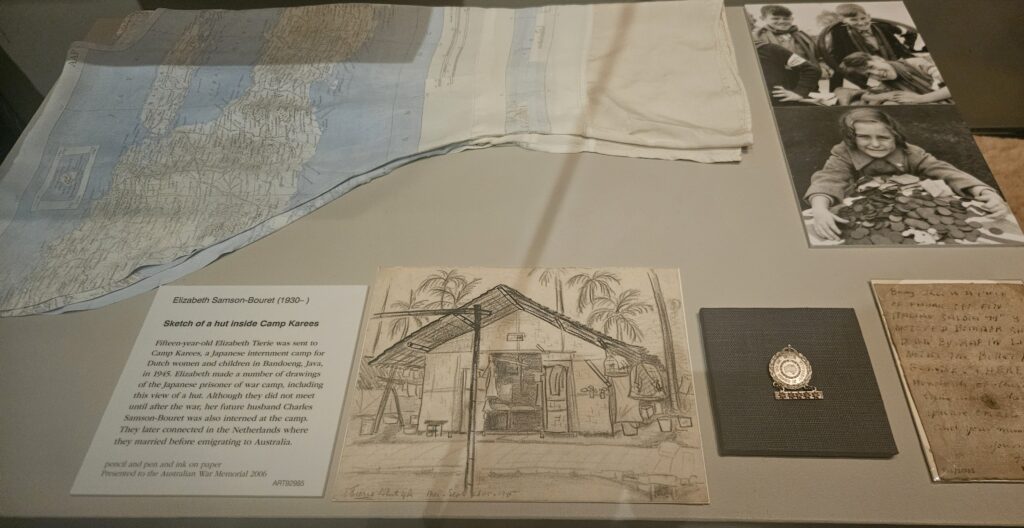

Kamp Kareës

Camp Kareës, situated in the southeastern residential district of Bandung, West Java, served as both a civilian and relief camp during a critical period in history. Functioning from December 4, 1942, to December 21, 1944, as a civilian camp, it later transitioned to a relief camp from October 1945 to December 25, 1945.

Located amidst Papandajanlaan, Tangkoeban Prahoe-laan, Wajanglaan, and Boerangranglaan, Camp Kareës accommodated approximately 6000 internees, including elderly men. The camp’s infrastructure prohibited private cooking, necessitating reliance on meals provided by a central kitchen. Strict regulations forbade trading for food from external sources, with severe penalties for violations. Described as a cluster of houses within a less affluent area of Bandung, the camp was encircled by ‘gedek’, woven bamboo sheets, topped with barbed wire fencing.

The Australian War Memorial holds several artefacts for people who were imprisoned in the Japanese camps on the Netherlands East Indies. They hold drawings from a collection of a total 28 drawings created by internees of Camp Karees in Bandoeng, Indonesia, during the Second World War. The drawings were presented to Mrs. Frederika Hessels Van Zalm, who ran the camp’s kitchen, as a token of appreciation for her dedicated work. Mrs. Hessels Van Zalm, along with her two daughters, Hanny and Dicki, her youngest son Dirk, and her father Dirk, were detained in Camp Karees, while her eldest son Fred was sent to a men’s camp. The drawings depict various aspects of daily life in the internment camp, including different internees going about their routines.