Early life in Noordwijk aan Zee

Agatha Neletta Koers was born in 1916, during the First World War. Although the Netherlands remained neutral, her family story recalls shortages and flooding that affected daily life. She grew up in Noordwijk aan Zee, where her father was a minister in the Gereformeerde church. The family lived in a village shaped by fishing, tulip and potato fields, and seasonal tourism, with dunes and a wide beach close to home.

She was the youngest in a large blended household: older half-siblings from her father’s first marriage and a younger group of children from her mother, Agatha. She later reflected that growing up in a busy household encouraged independence. The tone of her childhood memories is one of sobriety and discipline, but also warmth: books, music, hymn singing, and family humour. She remembered the power of congregational singing in a packed summer church and the rhythm of church life in a resort town.

The story also records early encounters with hardship: tuberculosis in the community, a young sibling’s sudden death from encephalitis, and the emotional weight that illness and loss placed on families at the time. Faith and the language of the Psalms became a practical resource in her childhood, used by her father both in church and at home.

Education and teacher training

Agatha attended local schooling and then entered Teacher’s College in Leiden in 1931. Her training was demanding and tightly structured, but she built strong friendships and developed a lasting love of literature, music, and the natural world, particularly flowers and plant identification. Her father died suddenly in 1933, a loss that reshaped the family’s circumstances and contributed to periods of prolonged sadness. During the Depression years she secured a teaching position in Oegstgeest, although at a fraction of the normal wage, reflecting broader economic conditions.

Alongside teaching, she joined a literature circle, wrote poetry, and took on leadership roles in church youth activities and choirs. Her narrative is unusually candid about confidence and insecurity, intellect and self-doubt, and the ways friends helped her recover from melancholy. This personal honesty becomes a consistent theme in later chapters of her life.

Posting to the Netherlands East Indies

In 1939 Agatha applied for a church mission teaching role in the Netherlands East Indies. She sailed from Rotterdam, arriving in Java in mid-1939. After a short stay with family, she took up work in Surakarta (Solo), teaching at a Christian girls’ domestic science high school and boarding institution. The school population was diverse, including Chinese students and Indonesian girls from Ambon and Java, and the institution carried strong ideas about women’s education and independence for the period.

Agatha developed her own syllabuses and learned Indonesian while managing heavy preparation demands. Her account describes both the richness of Indonesian life and a growing awareness of resentment among some Indonesian colleagues toward European rule. She believed she was generally respected because she avoided the arrogance she associated with some Dutch colonials.

Meeting Kees De Jong and the approach of war

Among the cohort of Dutch mission teachers was Cornelis Antonie de Jong (“Kees”). Their relationship unfolded against the tightening international situation after the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940 and the escalating threat of Japan in Southeast Asia. A shared holiday in the mountains at Tawangmangu and the climb of Mt Lawu became a turning point; their engagement followed, and they married on 1 July 1941 in Solo.

They moved to North Sulawesi (the Minahasa), where both worked in education. The marriage narrative, full of music, books, and long walks through tropical landscapes, sits in stark contrast to what followed.

Japanese invasion and internment in the Minahasa

After Pearl Harbour and Japan’s advance, Dutch men were called to military duties and the Minahasa was invaded. Agatha’s account moves through flight, hiding in the bush, surrender, and confinement, first in a convent in Tomohon under severe food restriction and fear of violence, then in other camp locations as the internment system expanded.

She records malnutrition, illness, poor sanitation, the deaths of children, and the psychological pressure of uncertainty about her husband’s fate. She also describes the moral and spiritual conflicts forced by Japanese demands for ritual obedience. At several points she depicts a loss of will to live, followed by interventions that restored purpose: caring roles, teaching younger girls, leading relaxation exercises, Sunday school, and helping organise camp routines.

Over time, the women formed leadership structures and allocated jobs. Agatha worked in storerooms and kitchens, distributing food and supplies. Later the internees were moved to a plantation camp at Lembean, where forced labour, disease, and death intensified. Her narrative includes malaria, dysentery, oedema, funerals led inside the camp, and the shock of learning of executions of men held elsewhere. It also records moments of human solidarity and the gradual lifting of morale as Allied aircraft appeared and the war’s momentum shifted.

Liberation, Morotai, and reunion

Agatha reports hearing of the Japanese capitulation in late August 1945, followed by a period of waiting before Allied forces could take control. She describes improved food supplies, medical support, and eventual transport to Morotai, where she assisted doctors by interpreting in English. Through contacts, she was able to pursue information about men transported to Japan, leading to renewed communication with Kees. They were reunited in October 1945 and spent a short period recovering together.

Postwar instability and the decision to leave

After their reunion they returned to the Minahasa and resumed teaching, but political instability quickly returned. The narrative records sudden evacuations, temporary returns, and the strain of living in a climate of fear and uncertainty. After time back in the Netherlands, they again attempted to rebuild in Indonesia, but by 1950 the situation had become intolerable for many Dutch families. They decided to migrate to Australia.

Arrival in Australia and Bathurst migrant camp

In January 1951 they arrived in Sydney and were taken to the Bathurst Migrant Reception and Training Centre at Kelso, travelling by train from Central Station. Agatha’s description captures the emotional contradictions experienced by many postwar migrants: institutional routines that triggered wartime memories, the stress of pregnancy and illness, and at the same time relief at food and safety.

She records being delighted to be allocated a private family room rather than being separated into dormitories. She also gives vivid, practical detail about early settlement conditions: flies, the shock of new food, and a gallbladder attack that led to hospitalisation. These grounded observations are part of what makes the narrative valuable as social history rather than simply family memory.

Agatha’s account of childbirth in Wollongong is especially frank: loneliness, language limits, and the sense of being pushed through procedures without the comfort of familiar support. Over time, stability grew through home ownership, garden self-sufficiency, church involvement, and the formation of Dutch and local friendships.

Corrimal and the Illawarra: building a new life

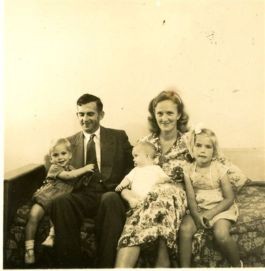

Kees took clerical work linked to the Port Kembla steelworks and commuted while they transitioned from camp life. They settled in Corrimal, purchased a fibro house, and began the slow work of rebuilding: furnishing on hire purchase, managing illness in young children, and navigating pregnancy and childbirth in an unfamiliar system.

Teaching, citizenship, and the long middle years

Both Agatha and Kees returned to teaching. The story reflects two parallel realities common among migrants of this era: the opportunities created by labour shortages and the persistence of prejudice and institutional barriers. Agatha gained an Australian Teacher’s Certificate and taught in increasingly multicultural classrooms. She describes classes with many nationalities and the practical daily work of teaching children whose lives were shaped by migration.

Kees’s recurring depression is a central undercurrent, with episodes affecting employment and family dynamics. Agatha’s narrative never turns away from this strain. Instead it shows how the family kept functioning through shared effort, supportive neighbours, community networks, and steady routines.

Naturalisation became part of their long-term settlement. The story records the administrative complexity involved, including travel to Canberra for documentation.

Sydney, Lugarno, and the move to Narrawallee

In the mid-1960s they moved to Sydney to support their children’s education, renting in tight conditions before building in Lugarno. Agatha worked in schools where migrant identity could still be used against her, even as she proved herself through competence and persistence. Family crises, health scares, and financial pressure recur, but so do friendships, church networks, and the quiet gains of stability.

In the early 1970s, as health issues and life-stage changes accumulated, they moved toward the South Coast and built in Narrawallee. This shift marks a transition from survival and settlement to a more reflective later life, centred on art, music, gardening, and community contribution.

Widowhood and community service

Kees died in April 1981. Agatha’s account of grief is understated but clear, as is the challenge of rebuilding a meaningful life alone. She became deeply involved in local church life, Meals on Wheels, visiting the elderly, and later, unexpectedly, church music. What began as a one-off request to “fill in” on the organ became an eighteen-year contribution to worship services.

Her story also records the delayed return of war memories, sometimes triggered by unexpected encounters or museum displays, and the slow process of speaking about experiences she had kept sealed for decades. Faith remains central throughout, not as an abstract identity but as a daily practice that helped her interpret suffering, restraint, forgiveness, and purpose.

Health challenges, family, and the final decade

Agatha faced serious health problems in later life, including cancer treatment and heart surgery. She continued drawing and painting, maintained strong family connections across Australia and the United States, and took pleasure in music, reading, and the view from her home. She died in June 2011 after a fall, following a day spent with family.

Source note

This article is based on the detailed family narrative published on the Waltzing the world WordPress site and reframes it as a Dutch–Australian life story, with emphasis on education, wartime disruption in the Netherlands East Indies, migration via Bathurst, and long community contribution in New South Wales.

Primary narrative source: Waltzing the world, Agatha Neletta de Jong (née Koers).