Pierre van der Eng

Dutch firm NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken exported its incandescent lamps to agents in Australia since 1912. Its lamp sales increased quickly during World War I, when Australian imports form the UK dwindled. In 1926 Philips established its own subsidiary company in Sydney: Philips Lamps (Australasia) Ltd. It imported lamps and other Philips electrical and electronic products, such as wireless radio sets, from Europe and distributed these to retailers in Australia.

During the 1920s, the Australian government encouraged import-replacing industrialisation. Its aim was to minimise imports and use the revenues from exports of wool and other primary products to service the country’s foreign debt. When falling international export prices hit Australia’s economy badly after 1929, the government increased import tariffs to create employment with industrialisation. By that time, the electrification of urban Australia had advanced. Electric light bulbs had become part of the daily requirements of its households. The Australian market was growing.

The initiative to establish a factory for incandescent lamps in Newcastle came from the Australian General Electric Company Ltd in 1929. However, the economical application of the automated lamp production technology required an annual output of at least 10 million lamps. To overcome that hurdle, the firm’s immediate parent, the General Electric Company Ltd in London started discussions with Philips and British Thomson-Houston Company Ltd. Together, these companies had in the late-1920s supplied 75% of the annual 12 million lamps imported into Australia for household use and in commercial and office buildings, as well as public lighting.

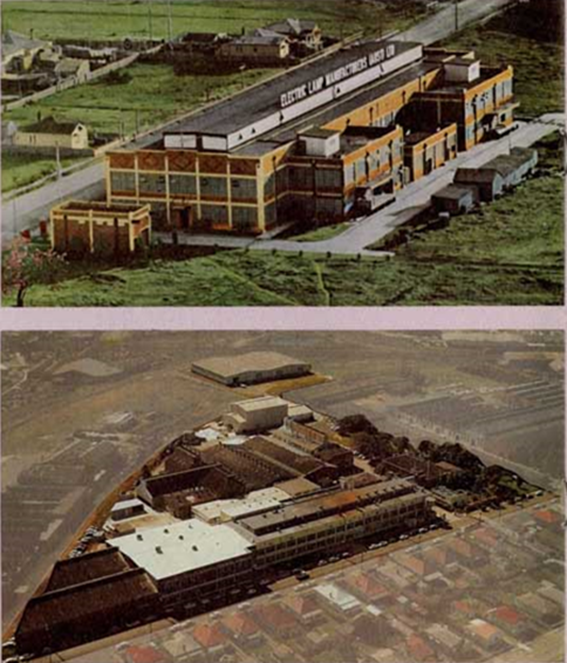

In July 1930 the three firms agreed to establish a joint venture company in Australia to produce lamps and committed to the construction of a factory on a seven acre bloc in the Newcastle suburb of Hamilton. Philips took the lead in supplying the machinery for lamp production, which arrived from The Netherlands in Newcastle in October 1930. With it came six Philips technicians who installed it and instructed the machine operators, as well as Philips managers to supervise factory operations.

When the global economic crisis after 1929 started to affect Australia’s economy, the Australian parliament in November 1930 approved an increase in import tariffs on electrical lamps to the equivalent of 12% from the UK and 60% from the rest of the world. An April 1931 Tariff Board inquiry trumped this by advising tariffs of respectively 27% and 87%.

Siemens Electric Lamps and Supplies Ltd (UK) joined the three. Together, the four parent firms established Electric Lamp Manufacturers (Australia) Ltd (ELMA) in March 1931. Among the 1930 arrivals from The Netherlands was former Philips employee Hessel Pieter Buisma (1898-1946). He became ELMA’s Factory Manager in 1931 until his premature death in 1946. His assistant Bernard Herman ‘Bob’ van den Berg (1904-ca.1980) succeeded him as Factory Manager in 1946 until he retired in 1967.

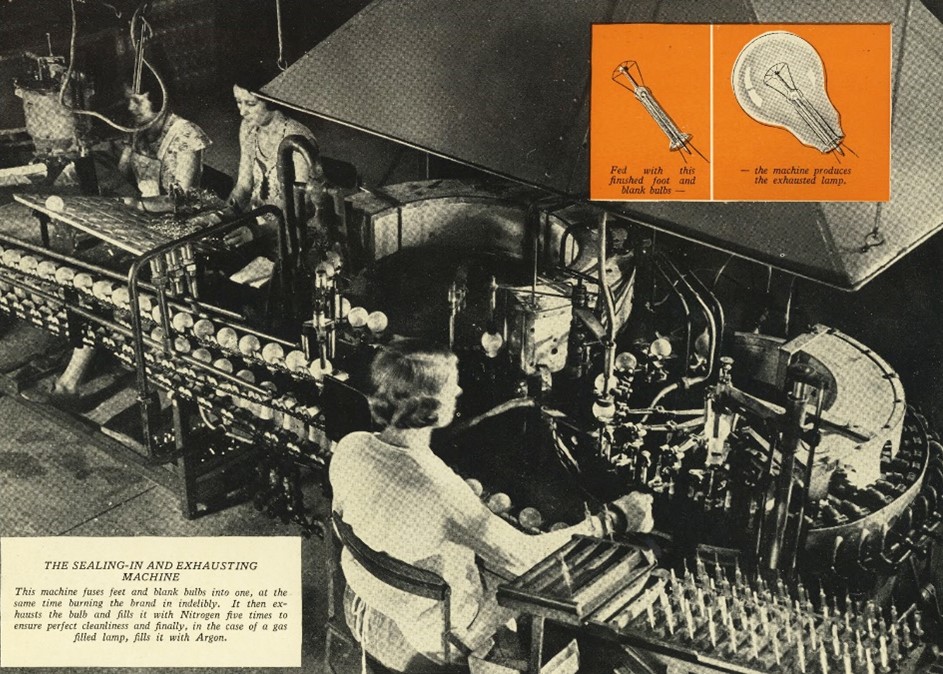

The ELMA factory was ready to start lamp production in February 1931. It supplied its lamps to the wholesale companies of the four ELMA shareholders in Australia. From there the lamps reached retailers and customers. The ELMA factory initially employed 53 men and 267 women for the assembly of electric lamps. Its production capacity was expected to increase in stages to 10 million lamps per year. The first expansion was in 1936 when new machinery arrived from The Netherlands, increasing the factory’s capacity to 5 million lamps per year. Australia’s lamp imports decreased as ELMA’s capacity grew.

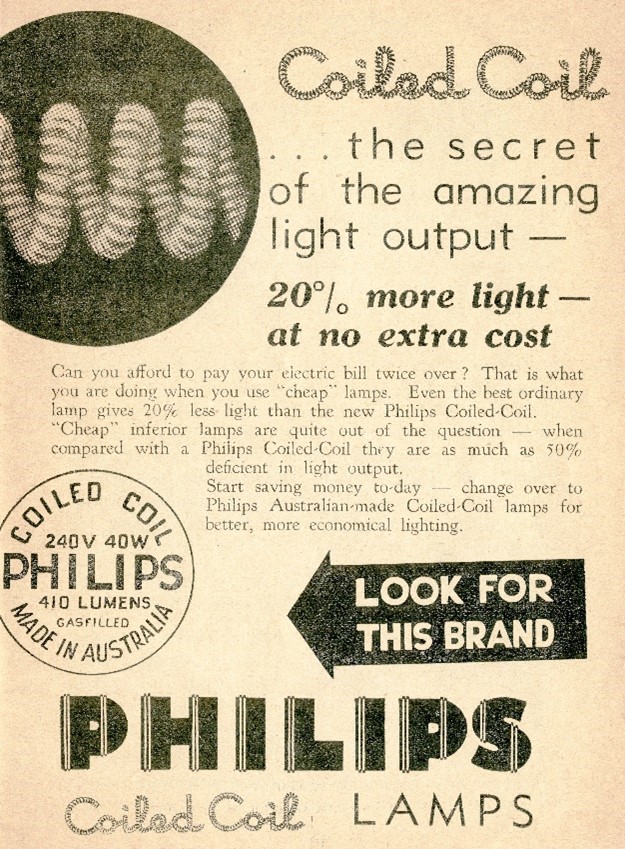

By 1940, Australian firms only imported various specialised lamps which ELMA did not yet produce. ELMA’s capacity had then increased to 11 million light bulbs. It produced lamps under the brand names of its shareholders: Condor, Ediswan, Mazda, Osram, Philips and Siemens. In 1943 Crompton Parkinson Ltd (UK) also acquired shares in ELMA, which added the Crompton brand to its production range. The same year ELMA started production of fluorescent tubes.

In the 1930s, ELMA depended on glass lamp bulbs imported from The Netherlands. In 1940 ELMA established a subsidiary, Newcastle Glass Works Pty Ltd (NGW). It opened a glass factory to produce lamp bulbs located next to the lamp factory and using local materials. In 1944 it expanded further with a separate office, administration and canteen building.

The Managing Director of the glass factory was another former employee of Philips in The Netherlands who migrated to Newcastle: Pieter Philippus Gastelaars (1901-1984), who left The Netherlands for Australia in April 1940, just before the German occupation. After his retirement in 1963, Gastelaars remained in Newcastle, where he was honorary vice consul for The Netherlands until 1972.

Although Philips in The Netherlands owned 35% of ELMA’s shares in the 1930s, the company operated as a Philips subsidiary. It maintained close relations with its sister company Philips Lamps Australasia Ltd in Sydney. The sister firm acquired almost all Philips-branded lamps from ELMA, which it distributed and marketed throughout Australia. And it continued to supervise ELMA’s operational management on behalf of the lamps and light division of Philips in The Netherlands.

ELMA’s four owners effectively operated a cartel that largely controlled Australia’s markets for incandescent lamps and fluorescent tubes. Cartel-like behaviour was not uncommon in Australian business at the time. Nor was it uncommon in the international lamp business, where the Phoebus lamp cartel dominated the industry until World War II. After the war, countries introduced policies to reduce anti-competitive behaviour of companies. In the UK this led to the breakup of the Electric Lamp Manufacturers Association after 1951. In Australia, it took 15 years before the 1965 Trade Practices Act required ELMA and other companies to register their cartel arrangements. But in ELMA’s case Australia’s trade practices tribunal did not impose restrictions.

Continued tariff protection meant that lamps sold in Australia were on average more expensive than overseas. ELMA actively used Australia’s commitments under the 1945 General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs to prevent ‘dumping’ of lamps by low-cost foreign lamp producers. For example, fluorescent tubes imported in 1968 from Japanese firm NEC or in 1986 from Germany and Canada.

Since 1931, the Tariff Board and its successor the Industries Assistance Commission reported several inquiries into lamps and fluorescent tubes that advised the Australian government to revise tariffs. Although import tariffs gradually decreased, they remained in place. For example, a Commission report in 1983 advised to leave tariffs at 10% for lamps and 20% for fluorescent tubes.

These tariffs contributed to continued employment at ELMA, which peaked at 750 in 1947. Further mechanisation and improved automation reduced employment until it remained around 500 during the 1950s-1980s. ELMA’s lamp factory employed mostly women in production of filament lamps. Of total employment of 373 in 1957, 213 were women, while the NGW factory employed mainly men to operate the glassblowing machinery; 149 in 1957.

Both factories expanded their production during the 1940s-1980s due to the growing market for electric lamps in Australia as a consequence of continued electrification and high population growth due to inward migration. In 1972 ELMA opened a separate fluorescent lamps factory which filled the remaining space on the seven acres plant. In 1980 it produced 48 million light bulbs and 11 million fluorescent tubes. With employment at ELMA and NGW of 565 that year, labour productivity increased significantly over 50 years through the modernisation of machinery and operations.

The gradual reduction of import tariffs increased competition in Australia’s market from imported lamps. By the 1990s, ELMA had become an anomaly in the global lamp industry. International trade liberalisation led to amalgamations of lamp producers. Global firms like Philips increasingly concentrated production in large factories in countries with lower labour costs, particularly in Asia. By international standards, ELMA operated a small plant.

Although ELMA persisted by increasing productivity, its profitability decreased during the 1990s. The company had four shareholders by then: Philips Electronics NV (Netherlands) 35%, Thorn Lighting Ltd (UK) 20%, Crompton Parkinson Ltd (UK) 10%, and the Rexel Group (France) 35%. They became reluctant to continue investing in upgrading machinery.

After ELMA lost $0.5 million during 2000 and 2001, the shareholders decided against investing $2 million in upgrading the glass factory’s blast furnace. They agreed to close the plant and wind up ELMA’s business. At closure, ELMA still had 220 employees, who produced 45 to 50 million incandescent lamps and 13 to 15 million fluorescent tubes annually.

See also:

Herman Diederik Huyer Managing Director Philips Australia

Frank Leddy reorganised Philips Australasia

More than 150 Dutch companies established subsidiary operations in Australia

Dutch involvement in the Sydney Opera House

The University of Newcastle has 500+ photos related to the company.