This is part of the story written by Maria Douwes, who emigrated with her family in 1960/1961 to Australia. This story is written by Maria Douwes and published in her book: Back to Australia.

The Douwes family was one of the last families to move from Amsterdam to Australia for a hundred guilders. Both the Australian and Dutch governments sponsored this trip. On December 9, 1960, Maria Douwes emigrated to Australia with her parents, five brothers and four sisters. They sailed via the Azores to Curaçao, through the Panama Canal to Tahiti and via New Zealand to Sydney. The story of their trip on the Zuiderkruis is available here.

January 1961

After a whole night in the train, half asleep, we arrive in Brisbane from Sydney. We get on a bus that takes us to Camp Wacol where we are registered. We are assigned four rooms in two different wooden houses. Our houses are right at the back of the camp, next to the railway. We hear the steam whistle and the locomotive in the distance. Every half hour a train passes by. In every room there are a couple of beds, some chairs and a cupboard. That’s all. We get our food at the canteen; we shower in separate shower buildings and there are laundries for washing our clothes. We get used to it quickly. In the morning we walk to the canteen with some of us kids, to get milk, buns, cornflakes, sausages and porridge. We eat that in our own house. You can also eat in the canteen but my mother doesn’t like that.

The wooden houses are in the middle of the bush. There are also steel huts, which they call ‘Nissan-huts’. It is really hot in there. It is not a real forest, the bush, it’s much wilder. There are snakes and large lizards, red ants that bite, you hear birds that laugh very loudly and scream and you see giant trees they call eucalyptus. -It really smells nice here. The koala bears that are native only eat the leaves of these trees. We don’t see any of them here in camp Wacol. We do see opossums, though. When it is dark you suddenly hear something just above your head making a sound, like sjsjsjsjs… The first time I was scared to death, by but Marianne, our neighbour, said: “Don’t worry, it’s nothing, it is opossum, they won’t hurt you.” They are as big as a small dog. I had never seen them in Artis, the zoo in Amsterdam.

The summer holidays are over and at the end of January we go to school. The wooden buildings with different classes of the school are spread out in between the trees. There’s no fence around them.

Our two eldest don’t go to school, they’re already working. Jos, (is a year older than I) and I are with miss Foreign and the older children are with Mr MacBurnie. Miss Foreign is very strict with us. We have to stand up straight when she enters the class and when she greets us with: “Good morning children,” we all have to say together, a rhythmical way and have to sing: “Good morning miss Foreign” or in the afternoon: “Good afternoon miss Foreign.”

Her face is plastered with make-up: a very thick layer of powder green eye shadow, and a bright orange lipstick. Her hair is dyed blond and done up high like my sisters do theirs sometimes with a thick layer of hair spray so it feels stiff. They call it a candyfloss. She screeches at us if we are not quiet or when we make a mistake. we have to stay after school time as a punishment. If I don’t finish my lines fast enough, she says all of a sudden and painfully slow with her face so close to mine I can smell her powder, her eyes half shut: “Dowsy dear, … out!” and I disappear as fast as my legs can carry me. What a bitch! She has no patience at all with children and we still have to learn English. Usually, I don’t even understand her. When Mr MacBurnie is around all at once she becomes as sweet as a rose. All smiles, shy and childish and crawling like a cat in heat she twists and turns all around him, but you just feel she’s false hearted. If he could only hear her raging at us for once, his eyes would open, I’m sure of that.

Luckily, Jos and I can go to the fifth grade after one month, where all our other older brothers and sisters are. With MacBurnie it is a party every day. We are with five of us and five of the Van Engelen family in one class. Also with some Finish people, Oerti and Marieta and a few Danes, of which Taje is about the same age as I am. We sing a lot. The first song Mac Burnie teaches us is: ‘Now is the hour when we must say goodbye: Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra sang this song and now we do. He says: “You have all just gone through this. Saying goodbye.”

Now is the hour when we must say goodbye Soon you’ll be sailing far across the sea When you’re away, oh please remember me When you return, I will be waiting here

The words are not difficult but I do find it strange to sing a farewell song when you’ve just arrived somewhere. We also learn the national anthem because Australia is part of the British Commonwealth. “The national anthem is also played after a movie the cinema,” MacBurnie tells us, “and then you have to stand straight. When you go to another school sometime soon, you’ll to sing it every day while hoisting the flag.” In Camp Wacol they don’t hoist flags. But we learn by heart:

God save our gracious queen She live our noble queen save the queen. Send her victorious happy and glorious long to reign over us God save the queen

So, we know it now and it will save us time later. If we don’t understand something the others who have been here longer, explain it to us. MacBurnie also has a game: ‘Do this, do that.’ He must say: “Alfredo says do this, Alfredo says do that“, and then you must copy his gestures. If he only says do this, do that, and you copy him you’re out and you have to take his place. And that’s how we learn English playfully.

If it becomes too noisy in the classroom, he will throw a piece of chalk at the biggest mouth, but if it really becomes a chaos, he will throw the blackboard brush at you, mostly quite effectively. It can really hurt. He doesn’t hit anyone though. Only the headmaster of the camp school does that. At other schools, all the teachers, male and female, will hit you. One even harder than the other. We don’t to go to a catholic school later because we heard that the nuns hit you on your legs with a leather belt with pennies in it. You are also obligated to wear a school uniform. Fortunately, we don’t have money for that.

Sometimes it is so hot here, that the asphalt is melting, so we all walk through the camp on bare feet. You hardly have any asphalt here. Most Australians also walk without shoes. Marianne, the little girl next door does it too. Only when we cross the road to the canteen there are some pebbles and it hurts a little. “After a while you don’t feel a thing anymore; you get calluses under your feet,” Marianne says. And she’s right. We only wear shoes to church now on Sundays and after that you take them off as soon as possible. Even Sonny Boy, the gardener, walks on his bare feet. “You can ask him for a penny, you know, then you can buy some sweets in the camp’s shop. He usually gives you something.” Marianne is already totally at home here.

Here in Australia, everything is different. For distances, capacities, and weights you don’t have kilometres, litres or kilos but miles, pints and quarts and gallons for liquids and Avoirdupois Weight for weights. It is very illogical and you have to learn everything by heart. Even the money is not divided into decimals. You have pounds, shillings and pence. Twenty shillings is a pound and twelve pence is a shilling. So, adding and subtracting money is much more difficult than with our guilders. You write a ‘£’ for pounds, an ‘s’ for shillings and a ‘d’ for pence. You write your numbers underneath them. But you really have to pay attention.

Avoirdupois weight goes like this:

- 16 ounces 1 pound

- 14 pounds 1 stone

- 28 pounds 1 quarter

- 4 quarters 1 hundredweight

- 20 hundredweight 1 ton

And lengths:

- 12 inches 1 foot

- 3 feet 1 yard

- 5 ½ yards 1 rod

- 4 rods 1 chain

- 10 chains 1 furlong

- 8 furlongs 1 mile

- 80 chains 1 mile

- 1,246 yards one mile

We also get spelling lessons: Awkward, a, double you kay, double you, a, are, dee. We just sit there with the class all chanting the same word over and over again. You get into a kind of trance. It’s rather nice actually. Another example is Mississippi: M, ai, s, s, ai, s, s, ai, pee, pee, ai. But that’s a joke, more or less.

The beating at school, would unleash a sort of uprising in the camp every now and then. That my mother had a leading role once, is etched in my memory because I was so proud that she defended my brother.

“She’s going after him; she’s going to hit him! Mrs Douwes is going to hit Mr Milton. He hit Hans and his eye fell out. Come on, let’s go and have a look. “From all sides I hear kids screaming at the top of their voices. I just come back from the canteen and everybody is running after my mother. So, I put the pans with our food in our house and I run as quick as a flash. I’m afraid I’ll miss something of this spectacle. I just see my mom waving with the big thick stick in her hand. You better save yourself if my mom is angry. She sometimes threatens us with a wooden spoon and hits you with it now and then. Better to scram when that happens. She’s already in the headmaster’s room when I arrive at the school. “Missers Douwes, please.. Missers Douwes, let me explain….” You, you,” and you can hear her lashing out. “Don’t Missers Douwes, stop…, auch, auch, stop it!” “And here’s another one! And another! You keep your hands off my children, understood! And here, here!”

Outside we’re all cheering. Everybody’s there. Not only the children from our class, but from all classes. Also adults. People from the kitchen, from the other houses, everyone has come to see what’s happening. My mother comes outside, still with a fierce look in her eyes. “And now, go home!” We don’t dare to speak to her. Around us we hear: “What happened? Did he lose his eye? Is Milton wounded? Didn’t Mrs Douwes get hurt? “Hurry up and eat. You will all have to go to school again soon.” You can almost touch the tension. We don’t dare to ask anything. We better just do what she says. Mom says “Hans, let me see your eye again.” The bleeding stopped. His eye is still neatly in its socket, and on his eyelid there’s only a small scratch. “You stay here this afternoon.” And that was that. My father is back home early from his job, in the afternoon. He had heard in the canteen kitchen, where he works, that there had been trouble at school and he wanted to hear the story first hand.

Almost everyone who hasn’t been in Australia very long, finds it difficult to be hit. Especially the older boys. Here it is legally permitted so we can’t do much about it. We didn’t have that in The Netherlands. You sometimes heard someone had been slapped for some reason or other. But here you are hit for almost nothing. Hans had been waiting for a friend who was being ‘caned’. Mr Milton and all other headmasters have a bamboo cane, and if your own class teacher thinks you have gone too far, he won’t hit you himself but he will leave it to the headmaster. If you have to go to the headmaster, you know it’s serious. So, Hans was waiting for his friend and Milton said, “If you think it is so interesting, you can come in as well.” He had to hold up his hand, so Milton could give it a good swing. But instead, Hans puts his hand in the air to avoid being caned. Now Milton thinks Hans is trying to attack him and he, in his turn, tries to avoid the expected blow and accidently touches Hans’ eye. Hans takes off and arrives at home with a bleeding eye and with Milton’s name on his lips. My mother was just doing the laundry and she was stirring it with a thick stick in a large pan with hot water. She doesn’t hesitate for one second and before Hans has finished his sentence, she is already running. She gives Milton a good spanking. Hans is sent from school and just for company Jos goes with him to the new school in Goodna.

In Slotermeer, where we lived in Amsterdam, it was already a big step forward if you had a separate bathroom, with a lavette: a round wash basin in which the little ones could sit and where you could wash your clothes. In the neighbourhoods Jordaan and the Pijp, there were no private bathrooms; people washed themselves at the tap in the kitchen or, when you were still young in a tub in front of the stove. In Camp Wacol there are wooden cabins with a bath, spread around the premises, and a sink and a bench for your towel and clothes. There’s also a whole new stone building with a lot of showers but I’ve never been in a full-size bathtub and I decide to take a bath. That is an unknown luxury. It is fantastic to rinse off the heat and dust from your body and to wash your black feet. You have to bring along your flip flops, for the way back. We have to go to bed with clean feet. Sometimes there’s a huge toad in the bath or one comes visiting while you’re in the bath. Or spiders, flying beetles, or all of them at once! It is also dark in there so eventually I go to the shower building that is a much longer walk. But there’s good lighting there and not so many insects and other animals.

A camera crew is visiting from The Netherlands. Hosts Netty Roosevelt and Pier Tania, cameraman Frans Verhey and Nick Hartog come to film for a documentary about Dutch immigrants. It’s for the Vara television and it will be broadcast in Holland in the summer of1961. They film at school and talk with a lot of people in the camp. My sister Agnes was seen on a full screen in her own class with other children, my grandmother writes in a letter later on. “She looked so serious” she writes. Not everybody likes it here. Some people miss the Dutch cosiness and the cold weather. In the evenings they film the English lesson for adults. Mr Nevel teaches: “In pronouncing’ th’, you put your tongue against your front teeth and blow softly. This, that and the other, think, that, there, thank, thorough”, he says and everybody repeats it after him.

If we want to go to town, we walk to Darra. Sometimes right through the bush but if it has rained a lot, the paths are impossible and then we walk over the railroad tracks. You hear the steam engines coming from a long distance and we jump aside on time. Through the bush we are sometimes scared to death. Then all of a sudden you are eye to eye with a large lizard. Sometimes a metre long or even longer with or without a blown-up collar, which stands as straight as a statue. One can be yellow, another one blue and yet another green or brown. Sometimes they suddenly change colour. You also see a snake sometimes, suddenly disappear. Usually, they are already gone before you see them because they hear your footsteps and they feel the ground trembling from far away. “They are more afraid of you than we are for them,” my aunt Suus says, who has been living here for a few years already. “You must pay attention for Death adders, Common Browns and Eastern Tigers because they are poisonous. But the best thing is not to touch them at all and stay away from them.” she says. “Just don’t take any risks.”

March 1961

We are going away for the weekend. Friday night we are picked up at Camp Wacol with a Volkswagen bus by our uncle Kees. We all fit in easily. We’re going to Redcliff on the coast. Aunt Coby and uncle Kees live there and uncle Bob and aunt Mien. Uncle Kees is an electrician and he can borrow the van from his boss. Uncle Bob is a tailor. That’s where Jos and I will stay. Their house is built on poles, but much higher than in the camp. It is so high that a car easily fits underneath. They say it’s against vermin but it’s also good for a cool breeze. In the morning we are up at six and we walk to the beach, which is close by. Bobby is the same age as Jos. We find a lot of dead young sharks on the beach, about as big as a herring. Also, beautiful shells. “You are only allowed to swim here where the lifesavers are.” Bobby tells us. They are on very high stools, ladders really, staring at the sea to see if they can spot any sharks. “When they see them, they take up their megaphones and call out: “Attention, attention, everybody out of the water. Sharks, everybody out.” Then everybody runs out of the water. A little later the sign ‘safe’ is given and then everybody goes back into the water, “says Bobby. For him its normal but we think it’s scary. Sometimes it goes wrong Then you read in the newspaper ‘Shark attack. Boy lost leg. His friend is missing’ Bobby hardly speaks anything but English, but we understand him. Aunt Mien told us that just a while ago a boy had a narrow escape. He went surfing with his friend when they were attacked by a ‘great white’. suddenly he saw a shark under his surfboard with its jaws wide open as large as a hippopotamus and with razorblade sharp teeth who bit off the entire back of the surfboard together with one of his legs. It could have been both legs. His friend who was surfing with him disappeared without a trace.

March 1961

Sometimes the whole camp school goes to the swimming pool of Inala. We go by bus. The father of a family from Limburg, a province in the south of Holland, comes along, Mr Jansen. They also came to Australia on the Zuiderkruis’. He’s the first to be changed into his swimming togs and is running along the side of the pool and taking a plunge, while turning around half-way and calling out: “Look, an Olympic dive!” He surfaces from the water laughing, with blood streaming all over his head, along his shoulders and arms into the water. He doesn’t notice anything himself until someone shouts: “You’re bleeding!” He grabs his head with his hand and looks at his hand. The dismay appearing on his face at that moment, affects us all. He can’t believe his own eyes. He didn’t feel anything, he says the next day. “Only later when the bandage was around my head, did I realise I had a hole in my head. I felt my head bumping against the bottom of the pool, but the stabbing pain came later.” Every time I bump into Mr Jansen after that, I see that triumphant laugh but bleeding head.

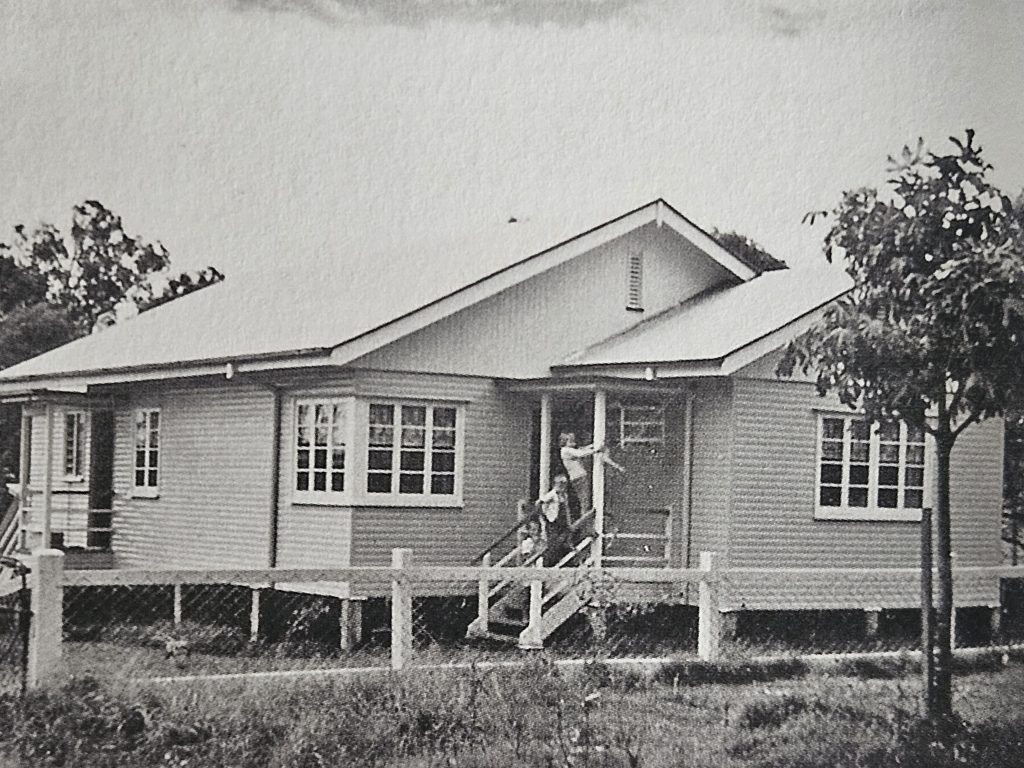

Inala

When we have been in Australia for seven months, we get a house at Poinciana Street 54, Inala. A lot of Dutch people and immigrants from other European countries live here. It’s a suburb of Brisbane, where the Queensland Housing Commission started building houses in the early fifties. It was built in the middle of the bush. That’s why, just before you move into a house, it has to be disinfected. It is built on poles, against snakes.