The newspaper article by Malcolm Quekett explores postwar migration to Western Australia through the history of the Graylands Reception and Training Centre, later known as the Graylands Migrant Hostel, and through the personal experiences of migrants who passed through it. The story brings together Dr Nonja Peters’ research on migration and the recollections of former residents Helene Melnema (née de Boer) and Brian Brown.

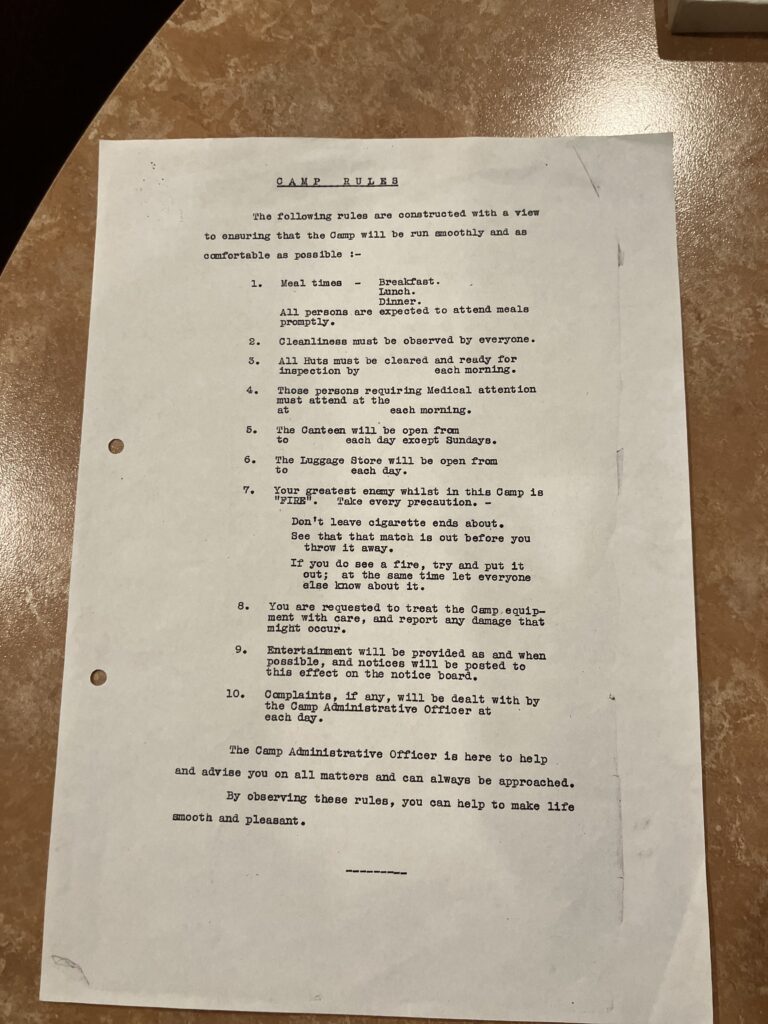

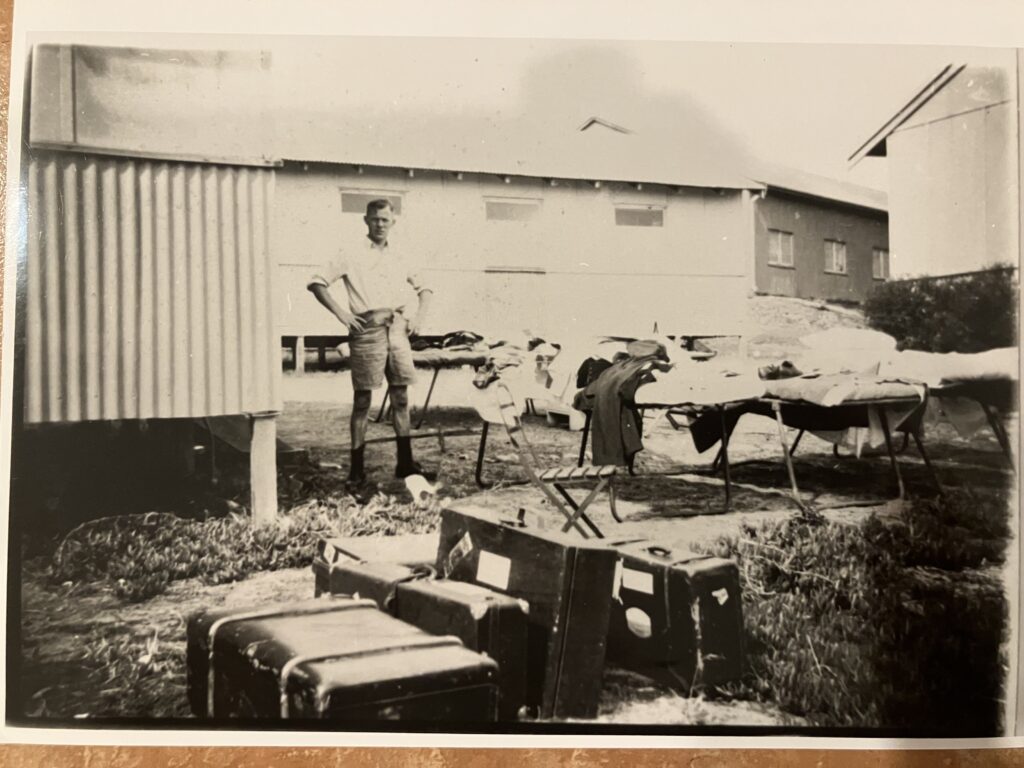

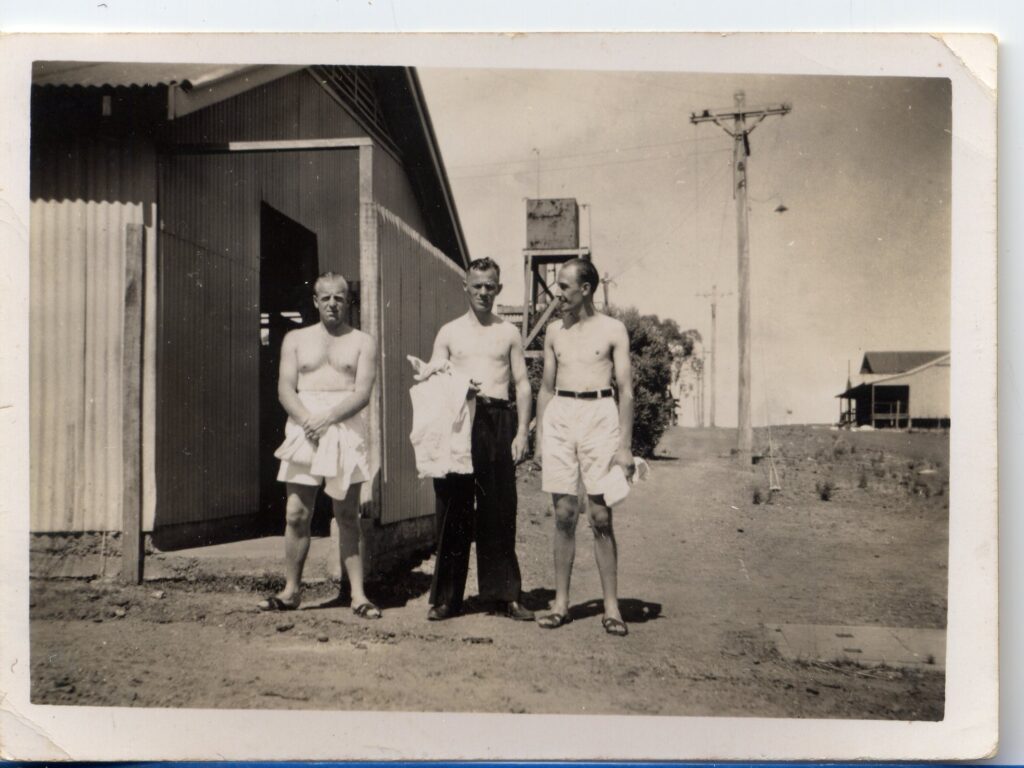

Dr Nonja Peters, a retired academic who has written widely on migration history, focuses her latest research on Graylands, near Mount Claremont, which from 1947 to 1966 housed thousands of newly arrived migrants. The article, however, often overlooks that the site in fact consisted of two separate camps. The first was the Department of Immigration’s Reception and Training Centre, operating between 1947 and 1952. This camp used unlined wartime army barracks and accommodated displaced persons from Europe, including Dr Peters’ father and his compatriots, who arrived in 1949 as part of the first Allied transport from the Netherlands. Photographs show newly arrived Dutch men, such as Jan Peters and Toon Berens, cleaning the barracks and standing with their luggage outside the ablution block—an unusual sight, since cleaning was not a common task for men of that era, suggesting the poor initial condition of the accommodation.

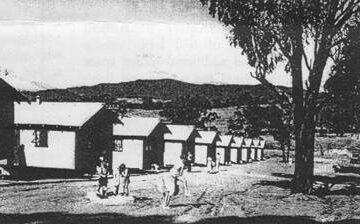

The second facility, established in 1951 on the adjoining land, was the Commonwealth Hostel, built with purpose-designed Nissen huts primarily for British migrants. These families were allocated a couple of rooms, representing a considerable improvement on the spartan barracks. Some Dutch families were transferred here from Northam once the fathers secured city employment. They later described the Nissen huts as “like Shangri-La” compared to the rough army accommodation they had first endured.

Peters explains that the postwar Australian Government, under the slogan “populate or perish”, sought to increase the labour force and strengthen national defence through large-scale immigration. The first arrivals came from Britain, followed by many from across Europe. She describes how Graylands’ communal facilities provided essential shelter and adjustment training, though conditions were austere, privacy scarce, and the food unfamiliar. Migrants faced culture shock, illness, and language barriers, yet many adapted and built successful new lives.

Helene Melnema arrived in Western Australia from the Netherlands in 1953 with her parents Johannus and Wietze de Boer and siblings. Before settling at Graylands, the family had been placed at the Holden Immigration Accommodation Centre in Northam. Melnema recalls Graylands as “like Shangri-La” by comparison, a friendlier place where her family could regain stability. She remembers attending Graylands Primary School without knowing English, the kindness of teachers and neighbours, and the sense of community among Dutch families. She recalls the simple pleasures—puffed wheat for breakfast, tomato soup for lunch, and plum jam sandwiches at school. Later the family moved into a house in Subiaco, taking in Dutch boarders while her father worked in the building industry. Her memories evoke both the hardship and gratitude of postwar resettlement.

Brian Brown, another former resident, arrived from England in 1958 with his family of seven. His father worked as a plumber at the Kwinana refinery. Brown describes Graylands as both lively and difficult, recalling walks to Claremont, school days at John Curtin High, and weekends exploring the beaches. Despite the rough conditions, he says, “I never looked back. I never missed the old country.” But he also notes that “many people could not handle it and went back,” reflecting the challenges of adapting to life in a new land.

By the late 1970s, the Nissen huts had been demolished and replaced with brick and tile buildings, complete with landscaped gardens and a swimming pool. The hostel also later housed asylum seekers and refugees from newer conflicts. By the time it closed in 1987, more than 35,000 migrants had passed through its gates, including Dutch, Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Romanians, and later Vietnamese and Iranians. The land was subsequently redeveloped, erasing most traces of the site’s migrant past. Dr Peters’ research aims to preserve those memories and will be made publicly available at the State Library of Western Australia.

Below are photographs from the collection of Dr. Nonja Peters