This is a abstract in English from a chapter in a Dutch paper, titled: Het verraad van Amerika en (vooral) Engeland (The treachery of America and (particularly) England). It doesn’t mention the author. The paper is part of the archive of Pieter Boele van Hensbroek and most likely was written by him. The archive is stored at the DACC,

This chapter, titled Australië en Nederland, explores the troubled wartime and postwar relationship between the Netherlands and Australia, framed within the broader context of what the author calls “the betrayal by America and above all England.” Drawing heavily on Dr Jack Ford’s Allies in a Bind (1996), it revisits how initial solidarity between Australia and the Netherlands over the defence of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) gave way to suspicion, hostility, and ultimately the rejection of Dutch attempts to restore colonial authority after Japan’s surrender.

At the outset of the Pacific War, Australia welcomed Dutch forces and civil authorities fleeing the Indies, seeing them as vital partners in deterring Japanese expansion. Yet, as the conflict wore on, Australian policymakers grew wary. Dr Ford highlights several causes: Canberra’s strategic shortsightedness, fears over migration and racial purity under its “White Australia” policy, ambitions for territorial control, and deep-seated doubts about Dutch military resolve. On the Dutch side, the author points to missteps by the government-in-exile in London, marked by conservatism, indecision, and a failure to grasp regional realities. The “Visman Report” of 1942, which recommended a gradual path toward self-government in the Indies, was shelved, reinforcing perceptions that the Netherlands was unprepared for change.

The chapter stresses that the Allies—Britain, America, and Australia—judged the Netherlands a weak power. Dutch resistance in Europe was quickly crushed in 1940, the NSB’s collaboration tarnished its reputation, and the defence of the Indies collapsed in early 1942. Although Dutch naval and merchant forces fought bravely, and individuals showed extraordinary courage, official Allied views often dismissed the Netherlands as unreliable. This perception fed into a climate where Dutch voices carried little weight in postwar planning.

The turning point came in 1945. When Japan capitulated, chaos erupted across Indonesia. The author argues that America’s unwillingness to deploy forces in NEI during this crisis amounted to a moral abdication, leaving a vacuum filled by nationalist revolution. Australia, far from supporting Dutch restoration, openly opposed it. Dutch officials in Brisbane and at Camp Columbia, where the NEI government-in-exile had its seat, were accused of arrogance and bureaucratic rigidity. Meanwhile, Australian politicians pressed their own claims in the region, while ordinary Australians, influenced by racial and colonial anxieties, showed little sympathy for Dutch ambitions.

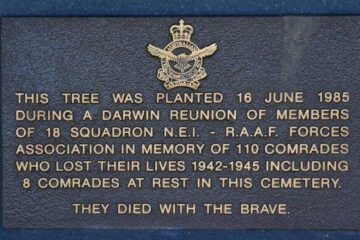

The text concludes that both sides shared blame. Australia’s xenophobia and parochialism collided with Dutch conservatism and miscalculation, producing a relationship that deteriorated from partnership in 1942 to near-hostility by 1945. Dr Ford’s key contribution, however, lies in uncovering the overlooked experiences of Dutch sailors, soldiers, airmen, and civilians who fought with courage and ingenuity. Beneath the layer of diplomatic friction lay countless acts of service and sacrifice—stories that deserve recognition against the stereotype of the Dutch as a “second-rate nation” that shirked responsibility.

For the Dutch-Australian community today, this chapter is significant not only as a historical analysis of missed opportunities and mistrust, but also as a reminder of the shared wartime experiences that linked both nations. It shows how geopolitical interests overshadowed human courage, and how those legacies continue to shape memory, identity, and heritage in Australia.