This memoir by retired air force colonel Jan Staal offers a vivid, personal account of the chaotic months surrounding the liberation of the Netherlands East Indies in 1945. Written decades later, it is both a critique of Allied leadership and a first-hand testimony of a Dutch officer unexpectedly caught between intelligence work, policing, and the politics of decolonisation.

The narrative begins with Staal’s irritation at British obituaries praising General Philip Christison as a liberator of the Indies. From the Dutch perspective, Staal recalls Christison not as a saviour but as the Commonwealth’s representative who actively undermined Dutch authority and prepared the ground for Indonesian independence at the expense of the Netherlands. This sharp contrast sets the tone: the author views Allied generals as shaping events in ways deeply damaging to Dutch interests.

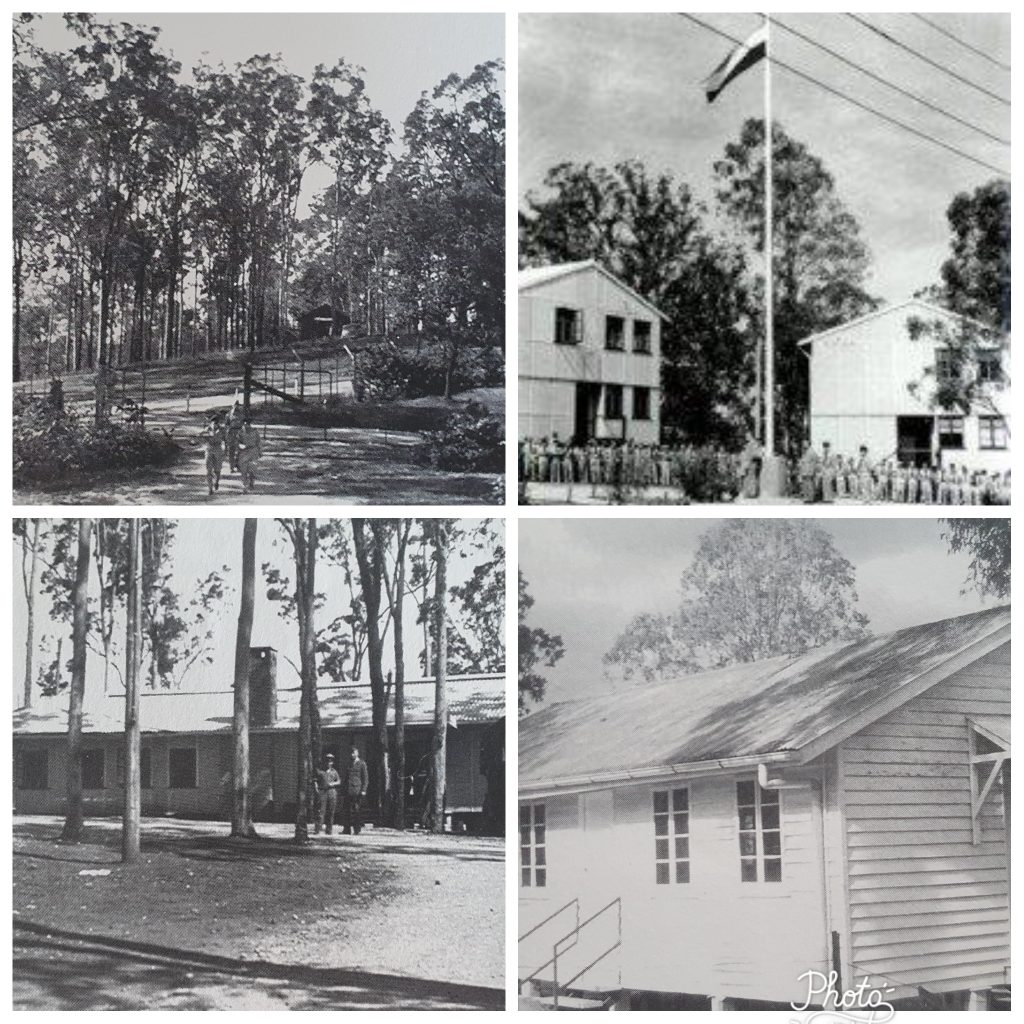

Staal’s own story resumes in 1944–45, when he was withdrawn from operational flying duties in 18 Squadron (B-25 Mitchells, Darwin) and reassigned to intelligence at Camp Columbia, Brisbane, under Colonel Simon Spoor. The camp housed both the Netherlands East Indies government-in-exile and military staff. There Staal helped build up NEFIS (Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service) and was soon dispatched to Manila, where he observed the immediate aftermath of Japanese occupation: guerrillas, collaborators, profiteers, chaotic policing, and American attempts at stabilisation. He returned convinced that unless the Netherlands acted decisively, the Indies would be lost to disorder. Spoor agreed, but government officials such as Van Mook dismissed warnings, clinging to the belief that the Dutch return would be welcomed.

Staal recalls the widening gulf between military realism and civilian complacency. Where intelligence reports foresaw turmoil, the government clung to optimistic illusions—Batavia’s trams running was taken as proof that “all was well.” Spoor urged preparation for policing and order; Van Mook and his circle underestimated nationalist currents.

By mid-1945 Staal was tasked with establishing a KNIL Military Police school, first on Tarakan, later in Melbourne. Hastily retrained ex-airmen were converted into policemen for upcoming deployments, a testament to improvisation amid collapsing structures. He describes the enthusiasm of Ambonese KNIL troops, the translation of American manuals into Malay, and field exercises against pro-Japanese bands.

Meanwhile, political pressures mounted. In Brisbane, union-led dock strikes, supported by pro-Indonesian activists, prevented Dutch ships from sailing. Tensions boiled over in Camp Columbia itself, where Van Mook nearly faced a mutiny of angry officials and soldiers frustrated by inaction. Staal depicts these episodes with bitterness, highlighting the lack of coherent leadership.

Returning with his improvised police units to Batavia in September 1945, he found the city outwardly calm but devoid of clear Dutch command. General Van Oyen, lukewarm and unprepared, received him with indifference. Orders were absent; political will was lacking. For Staal, this underlined the fundamental problem: the Netherlands had the men and skills, but not the political clarity or decisiveness to match.

The memoir thus paints a stark portrait of 1945 as a turning point:

- Spoor, Van Straten and parts of the military saw the dangers clearly and tried to prepare.

- Civil authorities, divided and complacent, failed to anticipate Indonesian nationalism.

- Allied figures such as Christison, Thorpe, and the Australian trade unions contributed to undermining Dutch authority.

- Improvised military-policing efforts could not compensate for political incoherence.

Staal’s recollections, coloured by personal involvement and hindsight, are critical yet valuable. They capture the atmosphere of uncertainty, frustration, and missed chances at Camp Columbia and in the early postwar Indies. For today’s reader, they illustrate how the Dutch transition from war to decolonisation was marked by confusion, poor coordination with Allies, and ultimately the collapse of colonial authority in the face of determined nationalist movements.

Jan Staal served as a captain-pilot-observer with the Military Aviation of the Netherlands East Indies (ML-KNIL) during the Second World War. After the war he continued his career in the Royal Netherlands Air Force, eventually reaching the rank of colonel before retiring (Kol. KLU bd.). There are personal archives of him at: Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie

This publication is part of the archive of Pieter Boele van Hensbroek (kept by the DACC)