In the decade following the Second World War, the Netherlands and Australia shared the vast island of New Guinea as neighbouring colonial powers. The western half, Netherlands New Guinea (DNG), remained under Dutch administration, while the eastern half, the Territory of Papua and New Guinea (TPNG), was administered by Australia under a United Nations mandate.

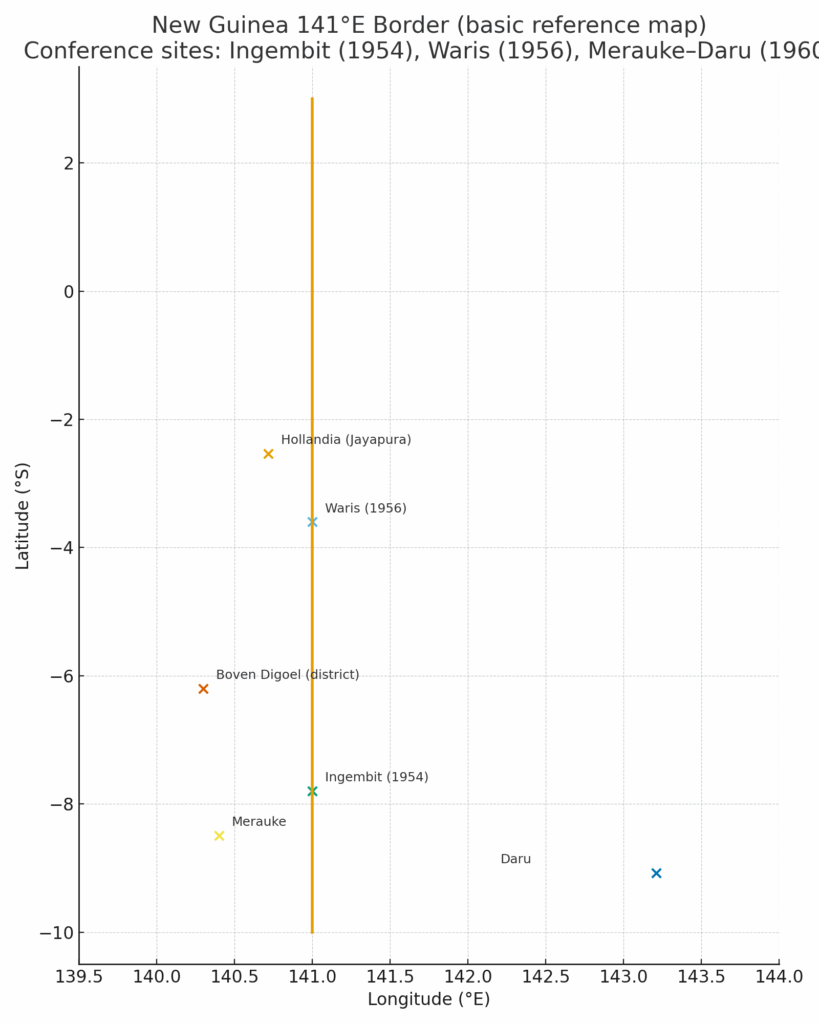

The boundary separating the two territories was fixed along the 141st meridian east. This line had first been defined in the Treaty between Great Britain and the Netherlands of 16 May 1895, which determined the frontier between British and Dutch spheres of influence on the island. The 141st meridian, running from the Bismarck Sea in the north to the Arafura Sea in the south, remained the basis for all later boundary arrangements between Dutch and Australian authorities.

By the 1950s, both administrations had extended their reach into the island’s interior, where the “paper line” often cut across traditional lands, villages, and trade routes. Cooperation became essential for effective administration, health control, and patrol safety in these remote and sparsely mapped regions.

The first meeting: Ingembit (Inggembit)1954

The first formal step toward coordinated frontier management came at Ingembit village on 10 September 1954. District officers from both sides met in the Boven Digoel area to discuss practical arrangements for governing local border affairs.

The resulting Ingembit Agreement—recorded in the Memorie van Overgave for Boven Digoel and later published by Paul W. van der Veur in Documents and Correspondence on New Guinea’s Boundaries—outlined procedures for mutual notification of patrols, handling of cross-border movements, and cooperation on health and quarantine measures.

Although modest in scope, this agreement represented the first structured collaboration between the two colonial administrations in the region. It set a pragmatic tone that continued into later meetings.

Expanding coordination: Waris 1956

Two years later, in 1956, Dutch and Australian officers met again at Waris, in the mountainous northern sector near the Sepik District. The Waris Conference expanded the earlier understanding by formalising systems for patrol coordination, information exchange, and joint mapping.

By this stage, relations between Dutch and Australian patrol officers were cordial and practical. They often exchanged radio contact, medical supplies, and aircraft support when working in adjacent valleys. The Waris Agreement essentially put these working habits into writing.

The final conference: Merauke–Daru 1960

The last major meeting before the transfer of Netherlands New Guinea to Indonesia took place in 1960, linking the coastal towns of Merauke (Dutch side) and Daru (Australian side). This conference dealt with broader topics, including coastal communication, fisheries management, and surveying of the southern maritime frontier.

The Merauke–Daru discussions marked the culmination of nearly a decade of cooperative administration. They reflected a mature partnership between two colonial systems that shared similar challenges of distance, infrastructure, and cross-border community life.

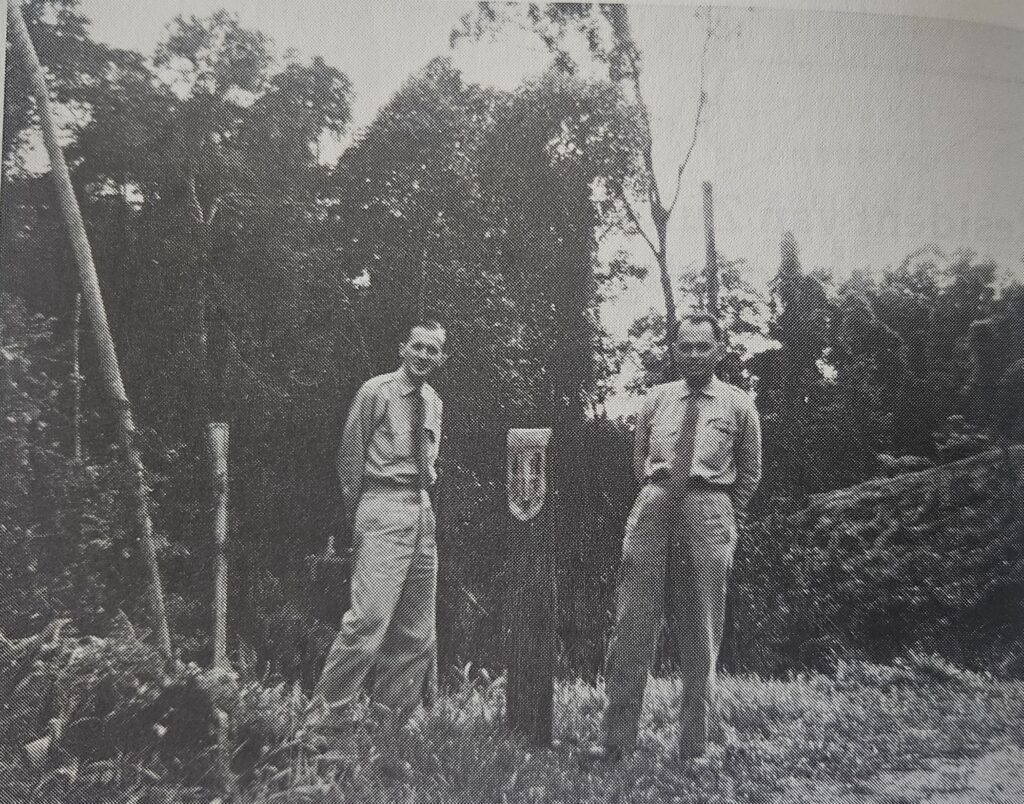

A field perspective: Pim Schoorl and Patrol Officer Baker

A valuable personal glimpse of how these agreements worked in practice comes from Dutch civil servant Pim Schoorl, then stationed in the southern border region. In his diary, Schoorl noted that on 16 May he received an invitation from his Australian counterpart, Patrol Officer Baker, to visit the village of Timin for discussions on a border issue.

He recorded:

On 16 May I received an invitation from my colleague in Papua, Patrol Officer Baker, to visit his village of Timin to hold discussions about border issues. Such an invitation could not easily be ignored, so I arranged a short tour from 19 to 24 May to visit him. It turned out that we would have to cross over to the other side of the international border, into Australian territory. According to Baker, a number of Papuans who had lived for about seven years on the Australian side now wished to return to our area. This matter, however, was in conflict with the Overeenkomst van Ingembit that he had signed with my predecessor, Cor Stefels. From my diary it appears that I assumed Baker was aware of the contents of that agreement, but I submitted the issue to the Resident for clarification. Source: Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945–1962,

Schoorl’s field note—confirmed by other colonial records—illustrates how local officers applied the Ingembit Agreement to real situations involving population movement and jurisdiction.

Pim Schoorl (1920–2013) later became a prominent Dutch anthropologist and historian, publishing widely on colonial administration and Papuan society. His early career as a field officer in Boven Digoel and Merauke gave him direct experience of frontier governance.

Little is known about Patrol Officer Baker, though records from the Australian administration of Papua and New Guinea indicate that he was one of several officers stationed near the Timin–Morehead region during the 1950s, responsible for maintaining liaison with Dutch authorities across the 141st meridian.

A frontier of cooperation

These agreements and local exchanges show that the Dutch–Australian border was managed more through communication than confrontation. Patrol officers like Schoorl and Baker were the true architects of frontier stability. Their cooperation helped to build a relationship of trust between the two administrations—an extension of the wartime partnership that had begun at Camp Columbia in Brisbane.

Legacy

When Dutch New Guinea was transferred to Indonesia in 1962, the frameworks created through the Ingembit, Waris, and Merauke–Daru meetings remained the foundation for managing what is now the international border between Papua (Indonesia) and Papua New Guinea.

Though largely forgotten, these border conferences reveal how post-war colonial powers could transform former wartime cooperation into peaceful regional governance—founded not on grand treaties but on mutual respect and practical problem-solving at the edge of empire.

Paul Budde October 2925

See also:

The Dutch Resident of Merauke visits Australian Papua New Guinea

Piet Merkelijn: bridging the Netherlands, Australia and Dutch New Guinea

Training Dutch officers in Australia for the Netherlands Indies and Papuan development

Research note

Primary sources:

- Memorie van Overgave, Boven Digoel, Appendix VI: Border Conference Ingembit Village (10 September 1954).

- Paul W. van der Veur, Documents and Correspondence on New Guinea’s Boundaries (Springer, The Hague).

- Nationaal Archief, Den Haag – Memories van Overgave collection (1852–1962).

- South Pacific Commission archives, for comparative context on regional administration.