The story of Dutch New Guinea in the 1950s is often told through the lens of Dutch colonial policy and the role of European missions. Less well known is the presence of small Australian evangelical societies. One of these was the Regions Beyond Missionary Union (RBMU), whose station at Wolo in the Baliem highlands became the site of a violent clash that drew Dutch officials into direct involvement. This episode highlights the unexpected but important cooperation between Dutch colonial authorities and Australian missionaries.

Background on the RBMU

The Regions Beyond Missionary Union was an evangelical mission society founded in Britain at the end of the nineteenth century, with strong support from Australia by the mid-twentieth century. In New Guinea, RBMU first established mission posts in Papua and the Australian Mandated Territory of New Guinea. In the 1950s it extended into Dutch New Guinea, where it became one of the few Australian-linked missions to operate before the transfer of sovereignty in 1962.

RBMU missionaries usually worked in remote highland posts, relying on Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) aircraft for supply and medical support. Unlike the large Catholic and Protestant missions long established under Dutch oversight, RBMU stations were small and vulnerable, making them more exposed to local conflicts.

The Wolo incident

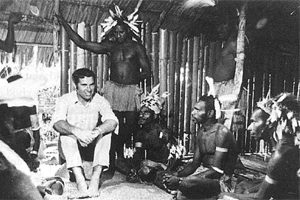

On 1 September in the late 1950s, the RBMU station at Wolo, north of the Baliem Valley, became the centre of a crisis. Two Australian missionaries stationed there had a dispute with local Dani villagers after a pig strayed into the mission garden. The quarrel quickly escalated into violence. The mission house was besieged by armed Dani, and one missionary was struck in the chest with an arrow.

MAF evacuated the wounded man to the CAMA mission doctor in Hitigima and dropped an urgent message at the Dutch government post in Wamena. Although the official policy of the colonial administration was that missions acted at their own risk, the officer in charge decided that abandoning the surviving missionary was impossible. He flew to Wolo with two police agents. After a tense night surrounded by Dani warriors, the police fired their Mauser rifles into a large tree trunk the next morning, shattering it with thunderous echoes. The show of force was enough to disperse the besiegers and end the crisis.

The incident revealed the fragile position of small foreign missions in the highlands, but also the willingness of Dutch officials to intervene when Australian missionaries were in danger. The Dutch–Australian connection here was practical and immediate: although they came from different traditions and national frameworks, the two sides depended on each other in this isolated and often volatile frontier.

Wider RBMU activity

The Wolo station is the best-documented example of RBMU work in Dutch New Guinea during the Dutch era. By 1962, however, RBMU had expanded further, sending Canadian missionaries Don and Carol Richardson to work among the Sawi people in the lowlands. Their experiences, later recorded in the book Peace Child, became internationally known. This confirms that RBMU’s presence in Dutch New Guinea was not limited to Wolo but extended across different regions and peoples.

Conclusion

The Wolo incident illustrates the Dutch–Australian connection in Dutch New Guinea in a direct and human way. Australian missionaries found themselves under siege, and Dutch officials risked their own standing to protect them. It was a moment where colonial governance and foreign mission work converged in the remote highlands, leaving behind a story that underscores the shared and sometimes fragile nature of cooperation in the last years of Dutch rule.