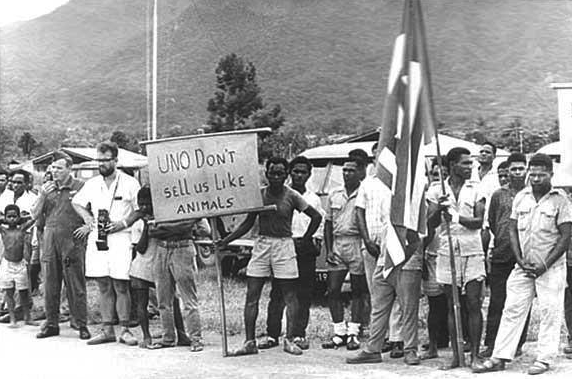

The transfer of Dutch New Guinea to Indonesian control in 1963 marked the abrupt end of one of the most promising experiments in decolonisation in the Pacific. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Netherlands had begun preparing the Papuan people for a future of self-government, establishing representative institutions and a clear political path toward self-determination. When the territory was transferred under the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA), this process was formally preserved in the New York Agreement, yet within months of Indonesia assuming control, Papuan national aspirations were suppressed.

The Dutch path toward Papuan self-determination

Following the Indonesian independence settlement of 1949, the Netherlands retained Dutch New Guinea as a separate entity, arguing that its Melanesian inhabitants were culturally and ethnically distinct from the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago. From 1957 onward, Dutch policy formally aimed to prepare Papuans for self-rule within a decade or more.

This program included the training of local administrators, the establishment of village and regional councils, and the creation of the New Guinea Council (Nieuw-Guinea Raad) in April 1961. The Council, composed largely of Papuan representatives, was intended to foster a new national consciousness. Later that year, the Council adopted national symbols: the Morning Star flag, the anthem Hai Tanahku Papua, and the name “West Papua.” The Dutch accepted these as expressions of identity and self-respect, not yet as independence, but they clearly indicated a path to nationhood.

The UNTEA transition and the New York Agreement

Mounting pressure from Indonesia, combined with diplomatic intervention by the United States, led to the New York Agreement of 15 August 1962. The accord outlined a two-stage process: Dutch administration would transfer the territory to UNTEA for several months, after which Indonesia would assume control, pending an eventual act of self-determination to be organised under UN supervision.

Between October 1962 and May 1963, UNTEA exercised limited administrative and security authority. The United Nations Security Force, composed mainly of Pakistani troops, maintained order while Dutch officials gradually withdrew and Indonesian civil servants took their place. The agreement guaranteed that Papuans would later be allowed to decide their own political future through a free-choice referendum.

Indonesia’s reversal of Papuan political freedoms

When Indonesia assumed control on 1 May 1963, it rapidly dismantled the institutions and symbols of Papuan identity. The New Guinea Council was dissolved, Papuan political organisations were banned, and the Morning Star flag and national anthem were prohibited. Indonesian officials declared that all such symbols represented separatism and were incompatible with national unity.

Dutch civil servant Arie Brand, who served in Fak-Fak during the UNTEA period, later described how Indonesian personnel and propaganda infiltrated the transitional administration. Though Pakistani troops officially oversaw security, Indonesian officials were already exercising informal control. Brand recalled that the atmosphere became one of intimidation and fear, with anti-Dutch demonstrations emerging overnight and political freedoms vanishing. He wrote that the situation reminded him of his youth under the German occupation, as freedom of expression disappeared and loyalties were coerced. The rights guaranteed in Article XXII of the New York Agreement – freedom of speech, assembly, and movement – were not honoured. Source: Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945–1962.

Brand’s account also highlights the indifference of many UN officials, who allowed Indonesian political influence to shape the mission. When the Secretary-General decided to terminate UNTEA ahead of schedule, the transition effectively legitimised the suppression of Papuan nationalism. What had been intended as a safeguard for self-determination became a rapid handover of power.

Australia’s role and response

Australia, which administered the neighbouring Territory of Papua and New Guinea, played a cautious and sometimes ambivalent role. Initially sympathetic to Dutch plans for Papuan self-rule, Canberra shifted position under pressure from Washington and London, both eager to stabilise relations with Indonesia during the Cold War.

During the UNTEA period, Australia maintained contact with the Dutch and the UN through its administrative mission in Port Moresby. It provided limited logistical and humanitarian support, including some air transport and coordination along the southern border. However, following the Indonesian takeover, Australia avoided public criticism of Jakarta’s actions. The Menzies Government judged that its strategic interest lay in a cooperative relationship with Indonesia, even if that meant turning a blind eye to the erosion of Papuan political rights.

By contrast, many Australians working in New Guinea at the time – including missionaries, administrators, and pilots – expressed private sympathy for the Papuans and concern over the abrupt end of Dutch initiatives. For them, the events of 1962–63 foreshadowed the complex postcolonial struggles that would later define the Pacific region.

Aftermath and legacy

The events of 1962–63 marked a profound turning point in Papuan history. What had begun as a cautious but genuine attempt at self-determination ended in political repression and the erosion of representative structures. For the Dutch, it represented the closure of a long colonial chapter; for Indonesia, the assertion of territorial integrity; and for Australia, a moment of uneasy acquiescence.

For those who lived through these events, the memories remained deeply personal. My aunt, Annie Budde, worked as a teacher in Merauke and Tanah Merah during the final years of Dutch administration. She witnessed both the optimism of the Papuan people and the uncertainty of the approaching transfer. Forced to leave in 1962, she devoted the rest of her life to supporting the cause of Papuan self-determination and to keeping alive the memory of the communities she had served. Her lifelong concern reflected a deep compassion for the Papuas and a belief that they deserved the right to decide their own future.

Six decades later, the hopes expressed in the Morning Star flag remain a potent symbol of the unfinished decolonisation process in the Pacific. The brief UNTEA interlude stands as both a gesture of international cooperation and a reminder of how easily the principles of self-determination can be overtaken by geopolitical realities.

Paul Budde October 2025

Research notes

Primary material on the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA) and the transfer of Dutch New Guinea (1962–63) can be found in the following archives and collections:

- KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) – holdings include administrative correspondence, reports from Dutch civil servants (including Arie Brand, Karl Knödler, and others), and post-transfer analyses.

- United Nations Archives, New York – UNTEA documentation series S-0858 and S-0859 contain reports from the Secretary-General, memoranda from the UN mission in Hollandia, and the complete text of the New York Agreement (15 August 1962).

- National Archives of Australia – Canberra and Darwin offices hold files on Australian liaison and observation missions to Dutch New Guinea during 1962–63, including Department of External Affairs and Defence correspondence.

- Australian War Memorial (AWM) – photographic and film records of the Dutch withdrawal and Indonesian entry, particularly those covering UNTEA .

- Papua Heritage and PapuaNet digital collections – include oral histories from Dutch and Papuan participants and later reflections on the transition period.

- Secondary source: Arie Brand, ‘Het UNTEA-bewind in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea, 1962–63’, in Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945–1962, ed. Jan van Baal (Leiden: KITLV Press, 1995), pp. 572–578.

Video: Vertrek Koninklijke Marine uit Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea (1962)