During the Second World War, Dutch and Australian servicemen fought side by side across the Netherlands East Indies. The swift Japanese advance in early 1942 saw the fall of Ambon, the Moluccas, and later Java, resulting in the capture of tens of thousands of Allied troops. Many of them were destined for a grim fate aboard the notorious “hell ships” – overcrowded, unsanitary transports that carried prisoners of war (POWs) and civilian internees between islands and into Japanese-occupied Asia.

The fall of Ambon and the Laha massacre

In late January 1942, Ambon was defended by a combined Dutch KNIL (Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger) garrison and Australian troops of Gull Force. Japanese forces landed on 30 January and, after fierce fighting, the defenders surrendered on 3 February. Within days, the Japanese carried out the Laha massacre – a reprisal for the sinking of a Japanese vessel by a mine. Over 300 Dutch and Australian POWs were executed, many by bayonet or beheading. Of the roughly 1,000 Australians captured on Ambon, barely one-third survived the war.

Java’s surrender and the dispersal of POWs

The Japanese landed on Java at the end of February 1942, and by 12 March the Netherlands East Indies had surrendered. On Java alone, around 60,000 Dutch troops and colonial personnel were taken prisoner, alongside thousands of Australians evacuated from Singapore and British forces from the wider region. The sheer numbers overwhelmed the Japanese, who quickly divided the POWs into groups for redistribution across their occupied territories. Many Dutch and Australians from Java were sent to Ambon, Flores, and other islands in the Moluccas.

The hell ships of the Moluccas–Java route

Transport between these islands was often by requisitioned merchant vessels, now pressed into service as POW transports. Conditions were brutal: cramped holds, inadequate ventilation, little food or water, and rampant disease. These voyages were also perilous—many ships travelled without Red Cross markings, making them indistinguishable from legitimate military targets for Allied submarines.

Three incidents stand out in the Java–Moluccas corridor:

- Suez Maru (November 1943): Carrying 547 Allied POWs, including 133 Dutch, from Ambon to Java, the ship – based in Fremantle – was torpedoed by the American submarine USS Bonefish, unaware it carried prisoners. Around 250 men escaped the sinking, only to be machine-gunned in the water by the Japanese escort vessel. Almost all aboard perished.

- Tango Maru (February 1943): This vessel, carrying hundreds of POWs and thousands of Javanese labourers, was sunk by the submarine USS Rasher near the Java–Ambon route. Only a fraction of those on board survived.

- Maros Maru (September 1944): Loaded with British and Dutch POWs from Ambon and surrounding islands, the ship sailed for Java but never completed its journey, with heavy loss of life reported.

Crushing the Japanese war effort – and the double cost of the hell ships

Allied forces, particularly submarine fleets, struck a devastating blow to Japan’s fighting capability by targeting its sea transport network. In total, approximately 1,200 Japanese merchant ships—amounting to roughly five million tons of shipping—were destroyed by Allied submarines throughout the Pacific War. This massive loss disrupted troop movements and supply chains and severely constrained Japan’s ability to reinforce its far-flung garrisons. Submarine warfare effectively “strangled” Japanese commercial and military shipping, cutting off oil, arms, and manpower essential to sustain its war operations.

Yet this success carried a tragic price. Many of these transports also carried Allied prisoners of war—unmarked and without any indication of their human cargo. As a result, sinkings that helped cripple Japan’s military capacity also claimed the lives of thousands of POWs, including Dutch and Australian servicemen captured in the Netherlands East Indies. Ships like the Suez Maru, Tango Maru, and others in the Java–Moluccas corridor became part of this double-edged reality: each sinking was a blow against Japanese logistics, but also a devastating loss of Allied lives, often of men already weakened by starvation, disease, and forced labour.

A shared Dutch–Australian ordeal

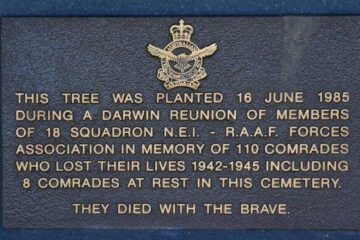

For Dutch and Australian POWs, captivity in the Moluccas often meant an initial period in harsh island camps followed by a hell-ship voyage to Java, Sumatra, or even Japan itself. These journeys compounded the suffering of men already weakened by disease, starvation, and forced labour. The shared experience forged bonds between Dutch and Australian survivors—bonds that continued in the postwar years, as many Dutch veterans migrated to Australia and joined local ex-service communities.

Remembering through history and film

The Andere Tijden documentary Hell Ships (in Dutch) tells this story through archival footage, survivor accounts, and historical analysis. It follows the path from Ambon’s fall and the dispersal of POWs through the Moluccas, to the fate of those loaded onto the ships. For descendants of Dutch, Australian and British servicemen, it is a stark reminder of the human cost of war and the shared sacrifices made in a corner of the Pacific that is often overlooked in broader WWII histories.