Declassified documents from the National Archives of Australia, researched by Ruby Todorovski, University of Queensland

Links to other declassified WWII Australian Documents re the Netherlands East Indies

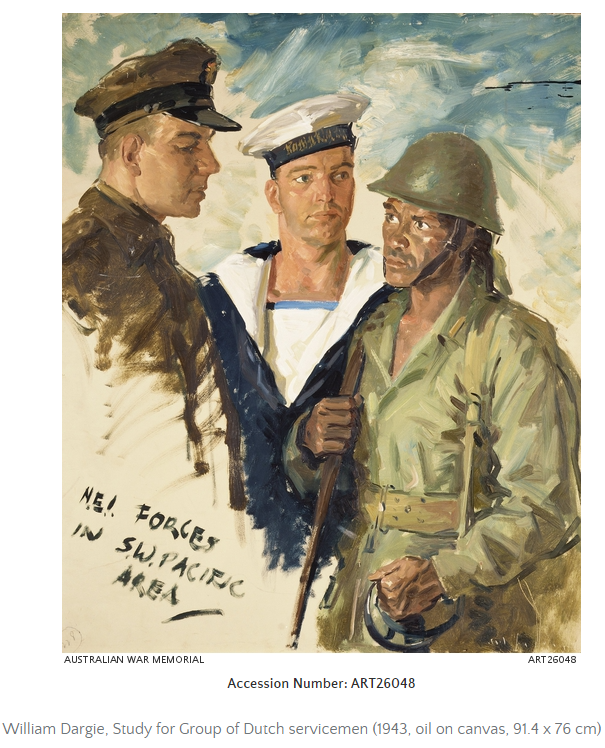

Military Command

After the surrender of the Dutch military in the Netherlands East Indies to the Japanese in March 1942, the Dutch military command ceased to exist in the region. Many Dutch military personnel were taken prisoner by the Japanese, while others went into hiding or joined the resistance. However, some were able to flee to Australia and to Ceylon.

Australia had no military industry of any significance to properly supply its military, let alone to assist the Dutch during its war with the Japanese. This led to diplomatic frustrations between both countries in the early days of the arrival of NEI government officials. The Netherlands expected more military resources from Australia than they were able to provide. With America taking over the leadership of the war effort in the South Pacific, significant military resources arrived from the US. This only changed when in the following month (April 18) the Dutch and the Australian military were placed under the command of Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), supplies now also started be become available from the US.

This was a result of the formation of the Pacific War Council in Washington, on 14 April 1942, with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and representatives from Britain, China, Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada. Representatives from India and the Philippines were later added. The council never had any direct operational control, and any decisions it made were referred to the US-UK Combined Chiefs of Staff, which was also in Washington. The Asian region stood under British control and the Pacific under American . There was a significant number of senior Dutch civil and military personnel at the Dutch Embassy in Washington to liaison with the Pacific War Council.

After the first level of chaos of the totally unprepared evacuation from key personal to Australia had settled down. NEICANZ began to rebuild the Dutch civil and military presence in the region. However, within weeks the decisions was made to split the civil and military activities.

While the Dutch were now under American Command, the Dutch Government remained adamant to keep as much as possible the Dutch presence in place as that would add to their legitimacy to recolonize NEI after the war.

The following are the key military commanders in Australia that had to maximise the contribution of the limited Dutch resource to the war effort.

Lieutenant Admiral Conrad Emil Lambert Helfrich who was send to Ceylon, just a few weeks prior to the surrender of the NEI, became the Commander in Chief of all of the Dutch and NEI forces in the Far East. Based in Ceylon that was far away from Australia were the largest part of the Dutch Forces were concentrated. Helfrich asked to be stationed in Australia but that was refused by the Dutch Government in London, who also wanted to stay close to the Brits. The Dutch Government wanted have a foot each in both the American and the British camp, this however was problematic with the small force that it had .

With NEI spreading out over 5000 kilometers some ships had escaped into the Indian Ocean and grouped in Ceylon. While others arrived in Australia. The Dutch Government was split about where to deploy their very limited military resources in the end they decided to keep it split between the British Command in Ceylon and the American Command in Australia. Helfrich reported to General Sir Archibald Wavell the British Commander of the South East Asia Command (SEAC). All of this complicated the communications issues for Helfrich as well as the Dutch decision making process.

Major-General Ludolph Hendrik van Oyen served as the commander of the ML-KNIL. During his time as commander, he was able to expand the view of the Japanese advance at the beginning of World War II. He played a significant role in the defense of the Dutch East Indies during the early stages of the war. He was among the last the flee from Java and became the Commander of all of the Dutch Forces in Australia (reporting to Helfrich) who had arrived in Australia and were now scattered all over the country including the planes, ships and personnel. He was placed under the overall command of General MacArthur. As would be the case during the war, the command structures were often complex and personal egos and county politics all played a role in this.

For unknown reason van Oyen himself as well as other senior personnel moved to the USA in April 1942 to set up the Dutch Military Flying School on Jackson, Mississippi. This left a gaping hole in the military top who were need for the active war effort. It was not until November 1943 before van Oyen came back to Australia and resumed his position as the Commander of all Dutch Forces in Australia.

At Archerfield Airport was an important group stationed to take possession of new American B-25 bombers and they were under the command of Major B.J. Fiedelij.

For other key military commanders see: The Headquarters of the Dutch East Indies Armed Forces (HK-KNIL) in Melbourne and Brisbane.

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force

The – in Dutch – Militaire Luchtvaart van het Koninklijk Nederlands-Indisch Leger, ML-KNIL was an entirely separate organisation from the Royal Netherlands Air Force. Like the NEI Army (KNIL) they resorted under the Minister of War at the Dutch Government-in-Exile in London. The Command structure as mentioned above applied to them.

Flying School

At a relative early stage it was decided to evacuate the flying school and the 300 students plus staff and families from Tasikmalaja (south east of Bandung) to Australia. In all 450 people boarded the MS Boissevain on February 14. They re-established at the RAAF Airfields of their flying schools at Mallala and Parafield, near Adelaide. The students of the Naval Aviation Service settled at Rathmines on Lake Macquarie. A further dozen single-engine flying boats were also brought to Australia.

The school would be one of the major contributions from the Dutch to the war efforts. Hundreds of pilots and flight-engineers were trained here and than brought to Australia to be deployed in the various squadrons. ( The Camp Columbia Heritage Association does have information on Willy de Eerens who was trained in Jackson, was stationed at Camp Columbia and tragically died in a plane accident in 1944).

See also: The evacuation of the Netherlands East Indies Flying Schools to Australia

Planes sold to the Allied Force (Americans)

It was only in the last days before the surrender that other military planes and their crews who were able to flee arrived in Australia (most without their families and their ground staff colleagues).

Once evacuated to Australia they were scattered around the country over the next few weeks the military command was busy organising the chaos and the planes were directed to bases at Bundaberg, Brisbane and Canberra.

A few weeks before the Fall of NEI a detachment of the Air Force was send to Archerfield Airport in Brisbane to collect B-25 bombers that were ordered by the Dutch Government. However, the first of these planes arrived after the Fall of NEI. The staff in Archerfield was trapped. They were not allowed to fly back to NEI to pick up their families.

The civil aviation company Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij – KNILM (Royal Netherlands Indies Airways) was already during the previous few month used by the Air Force and the military crew at Archerfield witness the arrival of the KNILM planes that eventuated with families and even household goods.

After the Fall all military and KNILM planes were handover to the Allied Forces, who were in desperate need of them for the defence of Australia and to stop further advances of the Japanese. This resulted in an already devastated NEI crew sitting idle for weeks on end. So it is not difficult to guess how bad the atmosphere was among these people.

18 NEI Squadron RAAF

Once more planes that were ordered by the Dutch started to arrive from America, the idea was born to establish a Dutch fighting squadron. Most of these planes went to the Americans. Eventually five B-25 bombers were allocated to the Dutch, these had to be shared among the 200 plus crew, so still a lot of sitting-around time. As Archerfield became to crowded, the Dutch were moved to Canberra where the 18 NEI Squadron RAAF was established on 4 April 1942.

Once operative they moved to McDonald, an airstrip in the bush, south of Darwin. The facilities here either din’t exist or were very primitive. They basically had to build an airbase from scratch. But finally after more than a year they now could be part of the action.

Royal Dutch Navy (Koninklijke Marine)

Unlike the NEI Army and Air Force, the Navy that operated in NEI, was part of the Royal Dutch Navy. They resorted under the Minister for the Navy at the Dutch Government-in-Exile in London.

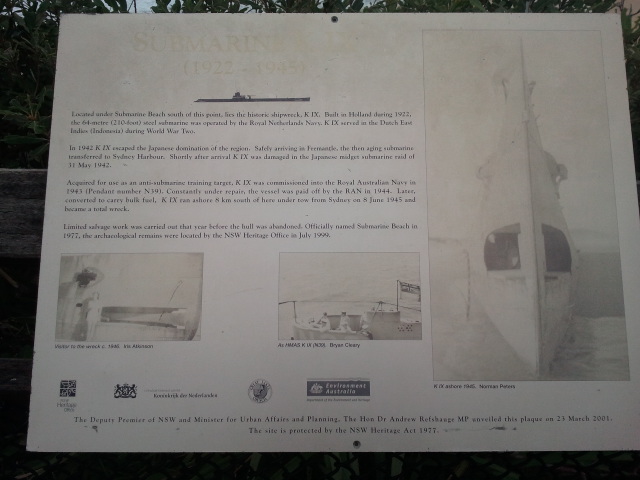

Once evacuated to Australia, the Naval Headquarters was established in Melbourne with subsidiary naval establishments in Sydney and Freemantle. The latter became the base of 15 NEI submarines. Many were lost at the start of the war, others participated in successful attacks on Japanese vessels.

About two third of all of the ships of KM were in NEI at the time of the breakout of the war here. So they were a formidable force and they were very important for the war effort of the Allied Forces.

Following the sinking of his ship during the Battle of the Java Sea , Rear Admiral Fokko Willem Coster had managed to escape and make his way to Australia. Helfrich appointed him as the Commander of the Dutch Naval Forces in Australia.

He also became the Dutch representative in SWPA in Australia. In his book Allies in bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two, Dr. Jack Ford stated that by 10 June 1942, Coster’s command totaled 1,353 personnel comprising 207 officers, four midshipmen, 18 warrant officers, 241 non-commissioned officers, 144 corporals and 739 ratings/other ranks.

In May 1943 Coster retired and his position was taken over by Acting Rear Admiral Pieter Koenraad.

Several measures were implemented to enhance oversight, administration, and coordination between the Koninklijke Marine (KM) and Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Given that the majority of Dutch naval personnel were stationed in Fremantle, Western Australia, Commander Gustaaf Berg was appointed as the senior Dutch naval officer in the region from July 1942. The KM established its local headquarters by acquiring an entire floor in the Colonial Mutual Life building on St. Georges Terrace in Perth. Additionally, every major Australian port had a designated Dutch naval officer responsible for overseeing Dutch naval and merchant ships that arrived.

To ensure the efficient operation of Dutch warships from Australian ports, larger KM warships carried a British Naval Liaison Officer (BNLO) and a small team of signalmen, radio operators, and coders. For Dutch warships arriving from Europe or the Indian Ocean, an RN liaison team was initially present, but this was later replaced by RAN personnel.

The Navy Airforce

After the chaotic evacuation and the dramatic destruction of many Dutch flying boats during the attack on Broome, the Navy Airforce concentrated its flying boats and personnel on Ceylon and became part of the 321 (Netherlands) Squadron RAF and was mainly involved in activities Under British command in South East Asia. One D0-24 flying boat was kept to cooperate with NEFIS and involved in intelligence missions in Dutch New Guinea and Timor. This was later extended with two more PBY-5 flying boats. Their flights generally moved up the east coast often stopping in Brisbane and Cairns before arriving in Merauke, the main town in unoccupied Dutch New Guinea. This detachment was further increased during 1945 and at that time they operated from the Qantas Airways facility at Rose Bay, Sydney. Other flyting boast were in May 1944 added to the 18 Squadron in Batchelor, Northern Territory.

The Merchant Navy

A significant contribution to the naval activities was the Dutch Merchant Fleet, one of the largest in the world and they played a crucial role in the transport of troops and material for the Allied (mainly US) forces in the Southwest Pacific. They operated from the Naval Control os Shipping (NCOS) with of fives in Sydney, Melbourne, Freemantle (this port had the largest concentration of Dutch ships), Brisbane and Townsville.

After the war the Dutch Navy could not immediately return to Indonesia. The Dutch didn’t have enough forces available to take over command from the Japanese, this was done by the British in their section and the Australians in the Pacific section. The Indonesian independence movement used this vacuum and this became a very violent period known ad Bersiap, where European and Chinese people were killed. This also forced many of the 100.000 women and children who were imprisoned in the Japanese camps to stay there. Furthermore back in Australia the Unions where boycotting Dutch transport to Indonesia- known as the Black Armada – as they supported the Independence movement.

Another problem were the mines that were laid by the Japanase. KM bought 8 oceangoing minesweepers from the RAN to help clearing these mines.

Most ships went to Indonesia in the first half of 1946. The Dutch depended for nearly 100% on supplies for Indonesia from Australia and the Black Armada made that very difficult. The head office in Melbourne closed in November 1946. However, Navy liaison officers were appointed and stayed in Australia. The last Navy ships left Australia in mid 1947.