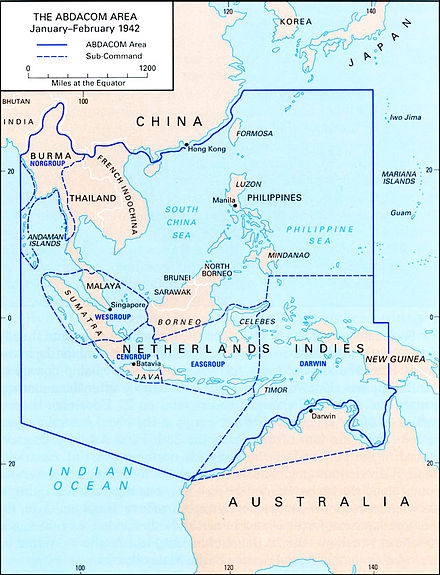

The American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) was the short-lived Allied supreme command for the South-East Asian theatre in the opening months of the Pacific War. Formed at Bandung, Java, on 10 January 1942 and led by British General Sir Archibald Wavell, it became operational only days after Japan entered the war. Its vast area stretched from Burma to Dutch New Guinea and the Philippines, and included the north-western approaches to Australia.

Its main task was to hold the “Malay Barrier”: a defensive arc running through Malaya, Singapore, and the southern islands of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). This barrier was intended to protect the Indian Ocean and prevent Japanese forces from advancing toward Australia.

The main objective of the command, led by British General Sir Archibald Wavell, was to maintain control of the “Malay Barrier”, a notional line running down the Malayan Peninsula, through Singapore and the southernmost islands of Netherlands East Indies NEI). Although ABDACOM was only in existence for a few months and presided over one defeat after another, it did provide some useful lessons for combined Allied commands later in the war.

Photos below are the arrival of the British General Sir Archibald Wavell at Kemajoran Airport on Januari 10 on his way to the inaugural ABDACOM meeting. He traveled in the Dutch Lodestar LT 925 Commanded by Res. Elt Yves “Bels” Mulder (Pilot). On board was also Brig Joop van Doorn, (Radio Operator).

The ABDACOM theatre of operation was huge, but its force was thinly spread , covering an area from Burma in the west, to Dutch New Guinea (DNG) and the Philippines in the east. The western half of northern Australia was added to the ABDA area.

On 19 February 1942, on Wavell’s advice, the Combined Chiefs of Staff decided to stop sending ground troops to Java as reinforcements. He had decided that Java was lost and no longer worth fighting for. These troops would be sent to Australia and Burma instead. The Australian army corps on its way to Java was therefore no longer to be shipped to Java. The island was thus, to all intents and purposes, given up. Wavell resigned as Supreme Commander, closed his personal headquarters and left Java on 25 February 1942. Dutch officers took command. Lieutenant-General H. ter Poorten, already the commander ABDA-ARM, also became the commander-in-chief for the ABDA area. On Java, ABDA-AIR was renamed Java Air Command (JAC) with Major-General L.H. van Oijen at its head. Vice Admiral C.E.L Helfrich was from 14 February the commander of ABDA-FLOAT.

ABDACOM timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 10 January 1942 | ABDACOM formed at Bandung, Java; Wavell appointed commander |

| 12 January 1942 | Japan declares war on the Netherlands |

| 24 January 1942 | Allied naval raid at Balikpapan; Dutch destroy oil facilities |

| 19 February 1942 | Japanese land at Timor; Australian and Dutch begin year-long guerrilla campaign |

| 15 February 1942 | Fall of Singapore; ABDA’s northern anchor lost |

| 27 February 1942 | Battle of the Java Sea; ABDA naval force destroyed under Admiral Karel Doorman |

| Late February 1942 | ABDACOM dissolved; Allied survivors evacuate or surrender in Java |

| 1942–45 | Surviving Dutch forces regroup in Australia, forming NEI squadrons within the RAAF |

Dutch participation and expectations

The Dutch decision to join ABDA meant relinquishing direct command of their forces. They did so on the basis of two promises:

- British confidence that Singapore could be defended, blocking the route into the Indies.

- Allied guarantees that reinforcements would be provided if the defence of Java required them.

Both promises collapsed in the face of rapid Japanese advances. Singapore fell in mid-February 1942, and no substantial reinforcements ever reached Java.

A fragile coalition

The four national partners had never previously coordinated at this scale. They used different equipment, had different training, and pursued diverging priorities:

- The British were determined to hold Singapore at all costs.

- The Dutch, whose military resources had already been weakened by the defeat of the Netherlands in 1940, concentrated on defending Java.

- Australia was heavily engaged in Europe and North Africa and could spare little for the Pacific in early 1942.

- The United States prioritised the Philippines, and General Douglas MacArthur paid little attention to ABDA command arrangements.

Dutch air power: strength on paper, losses in reality

At the start of the Pacific War, the Netherlands East Indies Air Force (ML-KNIL) was, on paper, larger than the Royal Australian Air Force in the region. Its frontline inventory included:

- about 80 bombers

- about 110 fighters of various makes

- around 16 light reconnaissance aircraft

- 19 transports

Further reinforcements were ordered but never arrived in time:

- 162 B-25 Mitchell bombers diverted to US use

- 162 Brewster dive-bombers reassigned to the US Navy and Marines

The Dutch deployed much of this strength to support Allied defence in Malaya and Singapore. In doing so, they lost the bulk of their bombers and fighters before the Japanese invasion of Java even began. By February 1942, only a handful of aircraft remained to defend the Indies alongside Australian squadrons.

In total, during the ABDA campaign the Dutch lost around 60 bombers, 70 fighters, and 7 transports, with many more aircraft damaged or grounded awaiting maintenance. These losses severely weakened the defence of Java and exposed the KNIL ground forces to Japanese air superiority. Around 800 KNIL personnel lost their lives during the Japanese invasion.

KNIL on the eve of war

The Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) counted roughly 60,000 personnel at the outbreak of the Pacific War, scattered across the vast archipelago from Sumatra to New Guinea. On paper this looked substantial, but in practice the force was thinly spread, poorly armed, and inadequately prepared for modern conflict.

Years of economic depression had slowed rearmament; it was not until the mid-1930s that serious efforts were made to strengthen the Indies’ defences. Even then, many of the weapons and aircraft ordered from abroad failed to arrive in time, as production bottlenecks and Allied priority demands meant deliveries were delayed or diverted.

The KNIL was also totally ill prepared for the scale of Japanese air attacks. Most units had no anti-aircraft defences at all, leaving them exposed to bombing and strafing runs from Japanese aircraft. In addition, they were greatly outnumbered by the invading forces, which combined overwhelming air superiority with experienced ground troops.

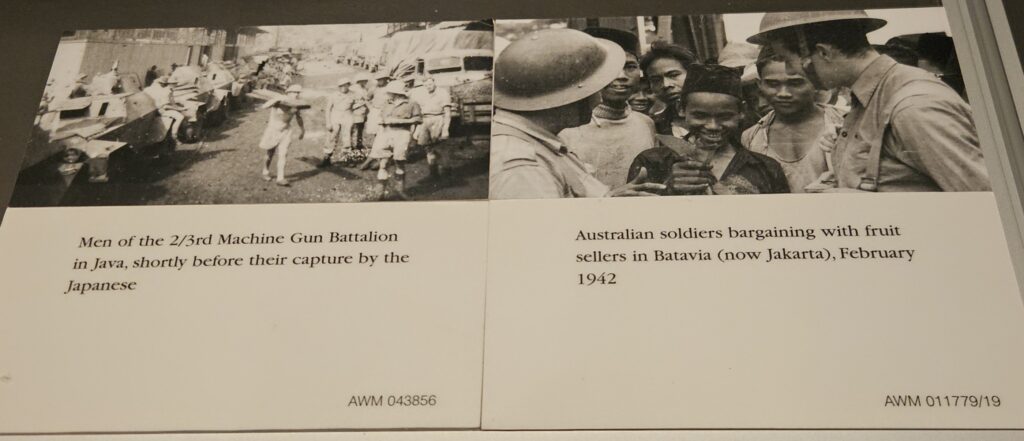

Together, these factors meant that when the Japanese offensive reached the Indies in early 1942, Dutch and Australian troops faced the enemy with depleted numbers, obsolete equipment, and almost no effective air cover.

Naval and ground actions

The Dutch Navy committed most of its modern vessels to ABDA operations. The combined ABDA fleet achieved some tactical successes, including sinking several Japanese transports at Balikpapan in January 1942. But the decisive Battle of the Java Sea on 27 February saw the destruction of Rear-Admiral Karel Doorman’s multinational force, marking the effective end of ABDA as a functioning command.

On land, Australian and Dutch troops fought side by side in Timor after the Japanese landings of 19 February. Their guerrilla campaign tied down Japanese forces for nearly a year. In Dutch New Guinea, a small garrison defended the Babo airfield long enough to destroy its facilities before retreating.

Legacy and Dutch forces in Australia

Though short-lived, ABDACOM revealed both the potential and the difficulties of multinational military cooperation. It was a model later improved upon in Allied command structures under General Douglas MacArthur. For the Dutch, however, the cost was devastating: much of their air and naval strength had been committed to defending Malaya and Singapore, leaving little remaining when the Netherlands East Indies itself came under direct attack.

The collapse of ABDACOM also resulted in a practical division of surviving Dutch forces between two Allied theatres. This division reflected both Allied command arrangements and geography. The Netherlands East Indies stretched over more than 5,000 kilometres from west to east, making unified defence and logistics increasingly unworkable after early 1942. Ceylon lay significantly closer to western NEI territories such as Sumatra and Borneo, which fell within the British sphere of operations, while Australia was better positioned to support operations toward eastern NEI and Dutch New Guinea under American command in the South West Pacific Area.

As a result, elements of the Royal Netherlands Navy and merchant marine regrouped at Ceylon under British operational control, while the bulk of Dutch air, intelligence, and remaining naval forces relocated to Australia. From 1942 onwards, Dutch airmen and sailors formed new units on Australian soil, including No. 18 (NEI) Squadron RAAF with B-25 Mitchells and No. 120 (NEI) Squadron RAAF with fighters. Operating within MacArthur’s command structure, these units carried the fight back into the archipelago for the remainder of the war.

Allied Defense of Netherlands East Indies

Abstract from the US Army document: U. S. Army Transportation, in the Southwest Pacific Area

See also: Unchained interests: A Dutch perspective on the failure of ABDACOM