In the years leading up to 1962, several Dutch, Papuan and Australian thinkers imagined a new political constellation for the Pacific: a Melanesian Union or Federation. This proposed bloc would have united Dutch New Guinea, the Australian-administered territories of Papua and New Guinea, and perhaps other nearby islands such as the Solomon Islands. It was a vision shaped by shared geography, ethnicity and a desire for regional self-determination—yet it was overtaken by global politics and the transfer of Dutch New Guinea to Indonesia under the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA).

Origins and advocates

The idea of a Melanesian Union surfaced in both Dutch and Australian policy circles during the late 1950s. In the Netherlands, it resonated with the growing emphasis on Papuan nation-building and regional cooperation under Governor Jan van Baal. In Australia, it appeared in public debate and among colonial administrators who were contemplating the future of the Pacific territories.

In January 1958, Australian legal scholar J. R. Kerr QC, formerly of the Australian School of Pacific Administration, argued that “every problem associated with New Guinea should be overcome by the formation of a Federation of Melanesia.” His comments reflected a strand of Australian strategic thinking that viewed Melanesia as a region better managed through federative cooperation than through isolated colonial regimes.

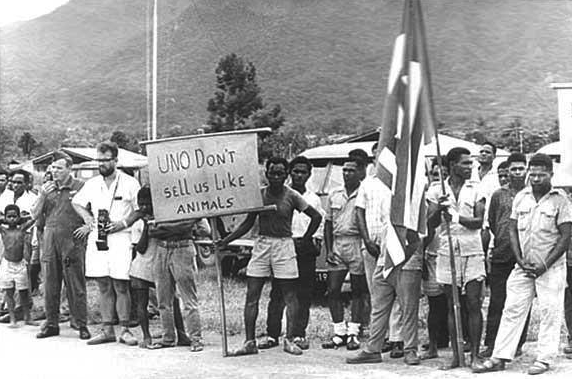

Papuan leaders also promoted the concept. Marcus Kaisiepo, a prominent West Papuan nationalist, travelled to the Netherlands in 1960, where he discussed an “independent Melanesian federation” that would unite West Papua, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. This was part of a broader Papuan effort to link their aspirations with regional decolonisation movements rather than presenting them solely as a Dutch colonial issue.

A similar idea appeared in the April 1961 issue of Foreign Affairs, which described a potential federation linking Dutch New Guinea, Papua, and other Melanesian islands. The article argued that these territories shared comparable development needs, geography and indigenous social structures, making them natural partners for integration once self-government became feasible.

Dutch and Australian perspectives

The Dutch viewed the Melanesian idea as a potential way to secure Papuan self-determination within an international framework, reducing tensions with Indonesia while maintaining a degree of influence. It dovetailed with Dutch plans for a gradual decolonisation process in West New Guinea, which included the establishment of the New Guinea Council (Nieuw-Guinea Raad) in 1961. That Council, largely composed of Papuan representatives, adopted national symbols and encouraged regional cooperation.

Australia, which administered the eastern half of the island under UN trusteeship, was interested but cautious. Minister for Territories Paul Hasluck and his officials at times considered federative schemes as one of several possible outcomes for Papua and New Guinea’s eventual independence. However, Australia’s growing alliance with the United States and United Kingdom meant it ultimately prioritised regional stability and cooperation with Indonesia over experimentation with new federative models.

Motivations and strategic logic

Proponents of a Melanesian federation saw both moral and practical advantages in the idea.

First, it acknowledged a shared Melanesian identity, linking the Papuans of the west with their kin to the east. This sense of cultural and racial unity offered a political narrative distinct from both Dutch paternalism and Indonesian nationalism.

Second, the federation could provide an administrative and developmental framework for territories facing similar challenges: rugged terrain, underdeveloped infrastructure and limited education systems. Joint development projects and regional governance could have accelerated self-reliance and reduced dependence on former colonial powers.

Third, in geopolitical terms, the federation offered a “third way” between the competing Dutch and Indonesian claims over West New Guinea. It might have allowed Papuans to achieve independence in concert with other Melanesian peoples rather than being absorbed into the Indonesian state.

Decline and disappearance of the idea

Despite its appeal, the concept of a Melanesian Union never advanced beyond exploratory discussions. Several factors contributed to its demise.

The first was the diversity of colonial arrangements. Dutch New Guinea, Australian Papua and British Solomon Islands each operated under different administrative systems, legal codes and international obligations, making any merger nearly impossible.

Second, the accelerating diplomatic crisis between the Netherlands and Indonesia over West New Guinea left little room for alternative solutions. When the United States brokered the New York Agreement in August 1962, all attention shifted to implementing the UNTEA transitional administration and managing the handover to Indonesia.

Third, neither the Netherlands nor Australia was willing to invest the political capital necessary to create a new Melanesian political entity. By the time of UNTEA’s arrival in October 1962, the idea of federation had been overtaken by immediate geopolitical pragmatism.

Finally, the concept suffered from internal fragmentation. Within Melanesia itself, linguistic and tribal divisions remained strong, and the population had limited exposure to regional political identity. As one observer later wrote, the idea of Melanesian unity was “an intellectual dream, not a political reality.”

By the end of 1962, as the Dutch withdrew and Indonesia prepared to assume control, the Melanesian Union proposal had disappeared from official discourse. What might have been a Pacific experiment in collective self-determination was lost in the tide of Cold War diplomacy.

Legacy

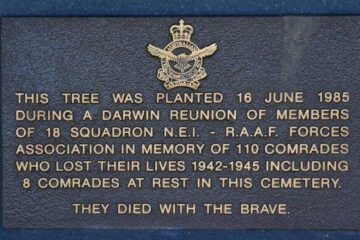

Although short-lived, the federation idea left traces that would reappear in later decades. In 1986, the establishment of the Melanesian Spearhead Group among Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and later Fiji revived the concept of regional solidarity. For Papuans, the federation vision remains a historical reference point—an early expression of identity distinct from Indonesia and aligned with their Melanesian neighbours.

The discussions of the late 1950s and early 1960s reveal how Dutch, Papuan and Australian policymakers briefly converged around a shared regional idea that, had circumstances been different, might have reshaped the political map of the southwest Pacific.

See also:

Dutch–Australian cooperation in the Pacific, 1947–1962

Research notes and sources

- Marcus Kaisiepo’s proposal for an independent Melanesian Federation, November 1960, discussed in History Beyond Borders

- “The New Guinea Question,” Foreign Affairs, April 1961

- Paul Hasluck and the Department of Territories: archival reference to the 1960 policy debate on “Unity in New Guinea,” ANU History series.

- UNTEA documentation, United Nations Involvement in West New Guinea.

- Discussion of atomistic federalism in Melanesia: ANU Open Research Repository .

- Secondary context: Dutch New Guinea policies from Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945–1962, KITLV Press, particularly essays by Jan van Baal and Arie Brand on decolonisation and self-determination.