In a striking twist of history, the Netherlands and Australia are converging around Indonesia’s deep human past. What began as a late-nineteenth-century Dutch scientific quest in the former Netherlands East Indies is now being reframed through Indonesian custodianship and contemporary Australian research. Anthropology, rather than diplomacy or conflict, has become the meeting point.

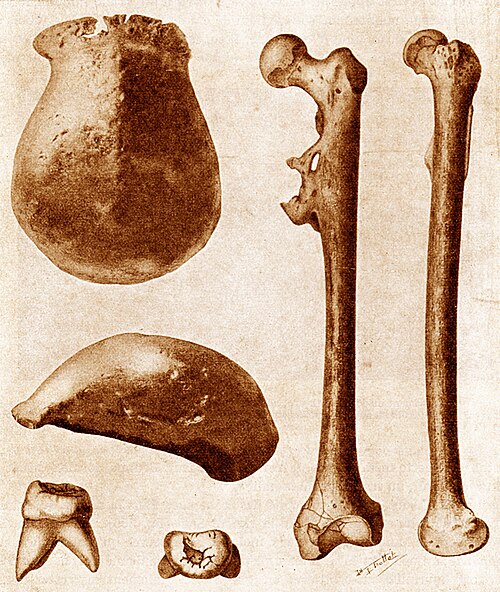

The story starts with Eugène Dubois, the Dutch physician-scientist who travelled to the archipelago in the late 1880s in search of evidence for human evolution. While Dubois is best known for his later discoveries on Java, his earlier work in the limestone caves of western Sumatra was extensive. Over a relatively short period he excavated numerous caves, carefully documenting geological layers and collecting thousands of fossils. Dubois himself was disappointed: he did not find the “missing link” he hoped for. Yet modern researchers have come to see his Sumatran work as scientifically significant in its own right, providing one of the earliest systematic records of the island’s prehistoric fauna and early human presence.

Like many collections assembled during the colonial era, Dubois’ fossils were shipped to the Netherlands and stored in Leiden for more than a century. For decades they were largely overlooked, overshadowed by the spectacular Java finds. That long afterlife in Europe has now reached a turning point. In 2025 the Dutch government decided to return the Dubois collection to Indonesia, recognising both its origin and its cultural and scientific importance to the country where it was found. With that decision, Indonesia has once again become the primary custodian of material that speaks directly to its own deep history.

At the same time, Australian scholars have played a growing role in reassessing what Dubois’ Sumatran material actually tells us. Recent research led in part from Griffith University has shown that his cave excavations were far from a failure. They yielded evidence of early modern humans in rainforest environments, insights into extinct animal communities, and data that remain crucial for understanding human and animal movement across Southeast Asia during the Ice Ages. This reassessment is reflected in the 2024 scholarly volume Quaternary Palaeontology and Archaeology of Sumatra, edited by Julien Louys and published by ANU Press, which brings Australian and Indonesian research perspectives together around Dubois’ legacy.

This convergence is not accidental. Australia sits geographically close to the Indonesian archipelago and has long been involved in archaeological and palaeoanthropological research across the region. Advances in dating techniques, palaeoecology, and landscape modelling — many developed or applied by Australian teams — have allowed older collections to be read in new ways. Questions that Dubois could not answer, such as how fluctuating sea levels shaped migration routes across the vast Sunda landmass, are now being tackled with interdisciplinary methods.

What makes this story particularly relevant today is its ethical dimension. Dubois’ work was carried out under colonial conditions, involving forced labour and extraction of material for European institutions. Acknowledging that context does not diminish the scientific value of the finds, but it does change how they are understood and managed. The return of the collection to Indonesia, combined with international research collaboration, reflects a broader shift towards shared authority and mutual respect in the study of the past.

In that sense, this is no longer a Dutch story or an Australian one. It is an Indonesian anthropology story, rooted in Dutch scientific history and advanced by Australian science, but centred on Indonesia’s landscapes, peoples, and heritage. The fossils Dubois once considered a disappointment are now helping to tell a far richer and more balanced story — one in which past and present, and multiple nations, finally come together.