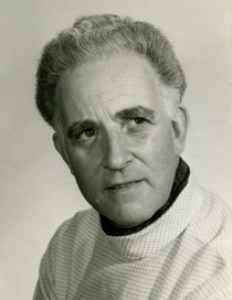

Not long ago, a book was published about Dick under the title The Incredible Life of Dick van Leer. This very readable account of Dick’s life, a family history really, written jointly with Aubrey Cohen, starts with his birth in 1922 in Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. Dick wasn’t there long though because his brother Ed suffered from severe respiratory problems. Their parents, Frans and Nettie, thought it better to return to the Netherlands in 1923. The first part of the book deals with the period to WWII. Dick attended the primary Willems Park School in Amsterdam, to 1933, at the same time as one Jeltje de Boer. Jeltje was born one day after him in the very same place in Surabya, the first of several coincidents in Dick’s life, who was actually named ‘Fransje’ originally. By 1925 Father Frans bought a half share in a wallpaper factory, Goudsmit-Hoff, which progressed to a successful, rapidly growing business, employing 200 staff by 1940. The family lived a comfortable and socially very active life in Amsterdam. Dick’s Mother’s Mother, Amelie Daniels lived and worked some years in Paris before being appointed as Head buyer for three well known Amsterdam fashion houses: Maison de Vries, Hirsch and Companie and, later, Maison de Bonneterie. Later, at age 55, she started a well-known shop ‘Paris Couture’ in Amsterdam. The Van Leer’s home in Amsterdam was a ‘social magnate’. Dick was sent to the Higher Textile School in Enschede in 1939/40 to study fabrics. It was in this environment that he developed competencies in the areas of weaving, designing and understanding style and fabrics. It would later be an asset for his work as a migrant in Australia.

However, all this came to an abrupt end in Amsterdam with the outbreak of WWII and the German occupation. The Goudsmit – Hoff company was confiscated by a competitor company from Germany. Persecution of Jewish persons resulted in extensive and daring underground activities of this secular Jewish family. Tragically, Dick’s parents were arrested, sent to Germany and lost their lives. Sadly, his Mother Nettie, having amazingly survived the concentration camp horrors, died on her way back home to Holland in 1945 due to typhoid fever. Dick spent a large part of the war period producing fake identity cards. He also worked as an underground labourer under a fake name (Johan Enno Fanoy) in Emmeloord, Noord Oost polder (reclaimed land), still later for a timber company in Oud-Karspel.

I asked him if he experienced anti-Semitic attitudes during his underground period from fellow workers. He said: “No, not all, not in that situation. We were all in the same boat and had to support one another and we all did”. After the war, in 1945 and 1946, he volunteered in three textile mills to obtain more practical experience. By interacting with the company directors he also developed business skills.

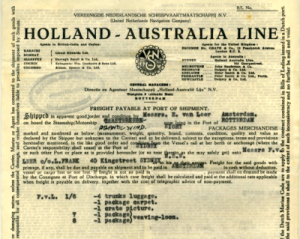

Dick decided to migrate to Australia and soon boarded a cargo ship from the Holland Australia Line, in Antwerp. The journey of no less than seven months was quite an adventure that took him to many ports, finally through the Red Sea and then to Sydney, all on his own. He had not expected the trip to last that long but he didn’t regret it. A part of the book describes his experiences en route in interesting detail.

Why did he decide to leave so soon after the war? He said, “I wanted out!”. Did anti-Semitism in the wider society play a significant role making you want to leave the Netherlands in 1946? “No”, he said. Why did you opt for Australia? Did you know much about Australia? “Not a thing”, he replied. “I had sent letters to Canada, South Africa and Australia, and I received prompt, positive replies from Australia”.

Where was his first accommodation in Sydney? This was well before the first migrant camps were established of course. “The only person I knew was To Pfeiffer (my aunt’s sister). I could stay there for two weeks. After I got a job I found accommodation with a Mrs. Brown, who lived in Mount Street, Coogee.” What were your very first impressions of Australia? “Well, it was quite different from war-torn Europe. It was peaceful, there was no damage in Sydney”.

He wrote:

“The first months in Australia were an eye opener. They were strange and exciting. Everything was new and different, part of a learning exercise, I carried a map at all times not to get lost. I had to get used to cars and driving buses on the wrong side of the road and had many escapes when I started crossing the road without looking for traffic from the right”… (p. 85)

Dick found work quite soon with “Coverings and Co”, Gardeners Road, Alexandria, as a loom tuner. The firm had imported top quality English looms from Hardackers with which he was quite familiar. The workers had problems to set the machines up and Dick was called in to assist, also with the associated Jacquard equipment, that uses punch holes (like a street organ). His wage as loom tuner was Pound Sterling 12.10 per week but it was doubled when he was able to provide training for others during installation, which covered about seven months. From Coogee to Alexandria was only 7 km and he usually went to work on an old bike without gears. This kept him fit but the first months were experienced as “very lonely”.

“At home in Holland, I had always enjoyed conversation and had taken company for granted. Stimulating discussions were part of everyday life so it came as a shock to spend so much time in silence because I had nobody to talk to. When I did speak it was mainly to discuss work with my workmates or exchange trivialities with shop assistants when I went shopping. This left a terrible feeling of emptiness during my first six months. It began the moment I left work every evening and became worse during the long winter nights. I write Ellen, my girlfriend, nearly daily. The weekends by myself were almost intolerable. The night seemed endless and the days dragged. I often felt that if I disappeared from the face of the world, nobody would know or care” (p. 88)

In this period he also became the representative of a Dutch textile company in Australia. Dick began to look for opportunities to set up his own business.

He anticipated the coming wave of migration from European countries well and a likely growing demand for more European styles fabrics as distinct from English drab patterns. He started a small importing business called Dinimpex (which still exists) with the aim to import European fabrics and textiles on an agency basis. They successfully imported a first batch from Helmond in Holland that sold well. But lack of capital to build up stock meant that income was limited to agent commissions. A sub-contractor used for deliveries, Arnold Coltof, owner of courier The Flying Dutchman, turned out to be an important intermediary for Dick. Coltof introduced Dick to the owners and founding directors of Artes Studio, Professor George Korody and his partner and financier, Elsie Segaert. Artes Studio, a new furniture and furnishings company in the heart of Sydney, introduced an avant-garde European approach shaped by the Budapest University Professor Korody. He had arrived in Australia in 1939 to design and set up the Hungarian Paviljon for a World Exposition. WWII broke out, Korody was stuck in Australia and the exposition was cancelled. Segaert ran a travel agency; besides her Artes Studio directorship she had little interest in the furniture business, while Korody was a brilliant designer but not a businessman.

“Until he arrived on the scene houses were largely dominated by heavy Queen Anne style pieces and the locals were not aware of – nor had they experienced modern design – so Artes became the pioneer of modern living in Australia. The new style, like the famous ‘Bauhaus’ style of Gropius and Mies van der Rohe” (p. 92).

Dick was able to invest in Artes Studio as a result of business developments in the Netherlands where his brother was in charge of the Goudsmit-Hoff family company that had restarted production after WWII. The brother was an excellent flautist and was more interested pursuing a professional career as a musician. A Belgian competitor offered an attractive price for the company, a good share of which was offered to Dick by Ed, which he accepted readily – it arrived at a most opportune time. However, there was a problem. The funds could not be exported due to the post-war Dutch Government restrictions. Here again, the intermediary Coltof came to the rescue, as he knew how this could be arranged. It was necessary to travel to the Netherlands and this was done some time later.

Meanwhile Dutch girlfriend Ellen had joined Dick in Australia after they had married by means of a ‘gloved’ wedding (by proxy). On arrival of Ellen they were married again in the Quaker meeting house. However, the romance experienced earlier, before Dick boarded the ship to sail to Australia had disappeared. Ellen was not really suited to running a household and wanted to do further studies at university. She had little interest in the life of a migrant in a country that needed “pioneering, courage and creativity”, as Dick put it. So the three of them decided to travel to Holland to collect the money. During the trip Ellen’s mental state deteriorated. Dick stayed eight months in the Netherlands to look after her. However, she didn’t want to go back to Australia and by mutual agreement the marriage was then dissolved. Arnold Coltof persuaded the Dutch authorities to release funds for Dick after which he became the fourth partner in Artes Studio, together with Segaert, Korody and Coltof himself. Dick was appointed General Manager.

Dick’s participative committee style of open management and further modernisation in styles and colours resulted in a successful retail venture in textiles and modern furniture design. This development is depicted in the book Mid Century Modern – Australian Furniture, and described as follows: “It brought forth an avalanche of modern furniture that was innovative, functional and imbued with a good dose of style”. Dick operated Artes Studio for 31 years. He was inventive and had as his life’s theme : “If it isn’t there, make it!”. The way the business was advertised can only be described as ingenious. A great variety of artists were encouraged to display their works in the shop: glassware, jewelry, cloth, fabrics, spinning, weaving and painting. They opened a gift shop as well. They offered clients to “make a home of your house”. Charities were assisted and through this Artes Studio gained further recognition and clients.

Amazingly, a Dutch customer turns up one day who states that he is the real Johan Enno Fanoy, Dick’s fake underground name during WWII! Still more amazingly, this man, who fled to from Zeeland (Netherlands) to Switzerland in 1940, is married to Jeltje de Boer (please read para 1 of this report). Dick calls it synchronisticy!

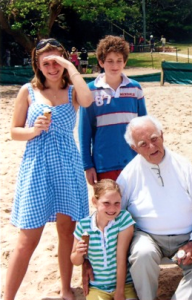

What about his personal life? He met his second wife Beryl Audet in 1950 at a Summerschool in Mittagong, a “deep thinker”, as he described her. They are married in 1955. Dick and Beryl become involved in a very large number of educational, artistic and musical pursuits. The harmonious marriage ended when Beryl sadly diesd of cancer in 1989. Their two children Madeleine (1955) and Julian (1957) attended a Rudolf Steiner school. The family’s connection with the Rudolf Steiner association and other philosophical societies continues.

Dick’s extensive involvements with the Anthroposophical Movement and his volunteer work with Life Line are truly impressive. It won’t come as a surprise that and 2, as well as other Steiner Schools.

Dick played St. Nicolas, on 5th December, for 11 years at Glenaecon R. S. School Kindergarten, classes 1

Artes Studio was sold by Dick in 1980 and from the proceeds some rental real estate was purchased to provide for a modest income allowing the family to pursue the various educational and volunteer interests, full time as it were. So, for instance Dick, after ten years of counseling became a Referral Officer with Life Line in 1985, often a very difficult task.

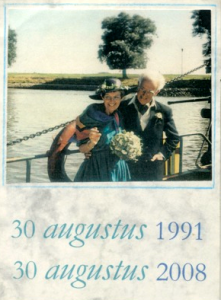

In 1991 Dick married An, a meditation teacher. An was a good friend of both Beryl and Dick. She lived in the Netherlands but later moved to Australia with him and is a soul mate. However, the couple first decided to live in the Netherlands, from 1991–1995. Dick expected a completely new Europe to emerge after the removal of the Berlin Wall and the end of Soviet Communism. This did not happen and they returned to Australia first to sort out some problems with Dick’s kids who lived in Australia. However, once back they also decided to stay in Australia altogether. The couple now live on the Central Coast, have travelled extensively and maintain an active network of social contacts.

Dick has been back in the Netherlands 14 times in all, often for business to study Dutch, Scandinavian and Italian new styles of furniture making, especially veneers on solid core, but also to visit relatives.

I finally asked him his views on migration in Australia. How has Australia changed? What has changed? He responded that:

- It has grown dramatically, fast, in many directions, like a rapidly expanding plant. It has become very multicultural.

- Australia has become more dangerous (natural disasters), there have been huge bush fires and massive floods, often, more often than in the earlier period after I arrived. The climate is changing.

- The concerns about asylum seekers, refugees and Muslims seem exaggerated. Refugees have adapted quickly in the past, are very motivated to succeed as migrants. There are many difficulties for a Liberal Government.

- I learnt a lot from how to get out of the victim role. Some refugees arrive because they are victims from political persecution. The way to progress is to take up the challenge and opportunity to succeed.

This is the life story of a very daring survivor of WWII and successful migrant to Australia who arrived here under his own steam, ahead of the later official migrant programs. His wide interests, humanitarian orientation and commitment to cultural and educational causes are highly regarded by many.

• Collated: 2014, Klaas Woldring

• Funded: Your Community Heritage Grants by The Department of the Environment, Canberra.

• Interview Series 2014: organised by Dr Nonja Peters, History of Migration Experiences (HOME), Curtin University, Perth Western Australia.

First published on Daaag