scroll down for: New research challenges the Batavia mutiny narrative

The Batavia – 1629

The Batavia, built in Amsterdam in 1628 was the company’s new flagship, she sailed that year on her maiden voyage for Batavia. On 4 June 1629, the Batavia was wrecked on the Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of small islands off the coast of Western Australia.

Five days after the disaster happened, Commander Francisco Pelsaert and skipper Arien Jacobsz with forty six others left in the ship’s longboat to search for water, ending up in Batavia and not returning for three and a half months, during which time a massacre occurred.

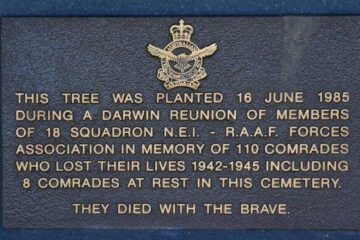

Francisco Pelsaert (c. 1595 – September 1630)

| A Dutch merchant who worked for the Dutch East Indies Company, who became most famous as the commander of the ship Batavia, which ran aground in the Houtman Abrolhos off the coast of Western Australia in June 1629. |

Following the Batavia shipwreck in 1629, a group of the marooned soldiers under the command of Wiebbe Hayes were put ashore on West Wallabi Island to search for water. The mutineers were secretly hoping that they would starve or die of thirst. However the soldiers were able to wade to neighbouring East Wallabi Island, where there was a fresh water spring. Furthermore, West and East Wallabi Island are the only islands in the group upon which the tammar wallaby lives. Thus the soldiers had access to sources of both food and water that were unavailable to the mutineers.

Later the mutineers mounted a series of attacks on the soldiers, which they were able to repulse. The remnants of improvised defensive walls and stone shelters built by Wiebbe Hayes and his men on West Wallabi Island are oldest surviving European buildings in Australia. The remnants of “the fort” are nothing more than a tiny, sandstone-coloured rectangle in the scrub about 100 metres from the sea. It is unimpressive and isolated and yet this simple structure, just some loose rocks piled up to make a simple fortress, saved the survivors of the Batavia.

Escapees from the bloodshed on Beacon Island alerted Hayes, and he organised the defence of his companions, repelling attacks from Cornelisz.

Replica of Wiebe Haye’s fortress on East Wallabi Island in Batavia Park, Geraldton.

The pictures above are made in 2018 remembering Wiebe Hayes and the first European ‘building’ on Australian ground. Wiebe was born about 1608, he was a colonial soldier from Winschoten, Netherlands. He became a national hero after he led a group of soldiers, sailors and other survivors of the shipwreck of the Batavia against the murderous mutineers led by Jeronimus Cornelisz .

In October, at the height of their last and deadliest battle, when Hayes and his men were able to capture Cornellisz they were interrupted by the return of Pelsaert aboard the Sardam. Hayes raced ahead of the remaining mutineers to warn him of their plans to overwhelm the rescue ship. Cornelisz denied all charges but there was plenty of evidence from the survivors to the contrary.

Pelsaert subsequently tried and convicted Cornelisz and six of his men, who became the first Europeans to be legally executed in Australia. Two other mutineers, convicted of comparatively minor crimes, were marooned on mainland Australia, thus becoming the first Europeans to permanently inhabit the Australian continent. Of the original 332 people on board Batavia, only 122 made it to the port of Batavia.

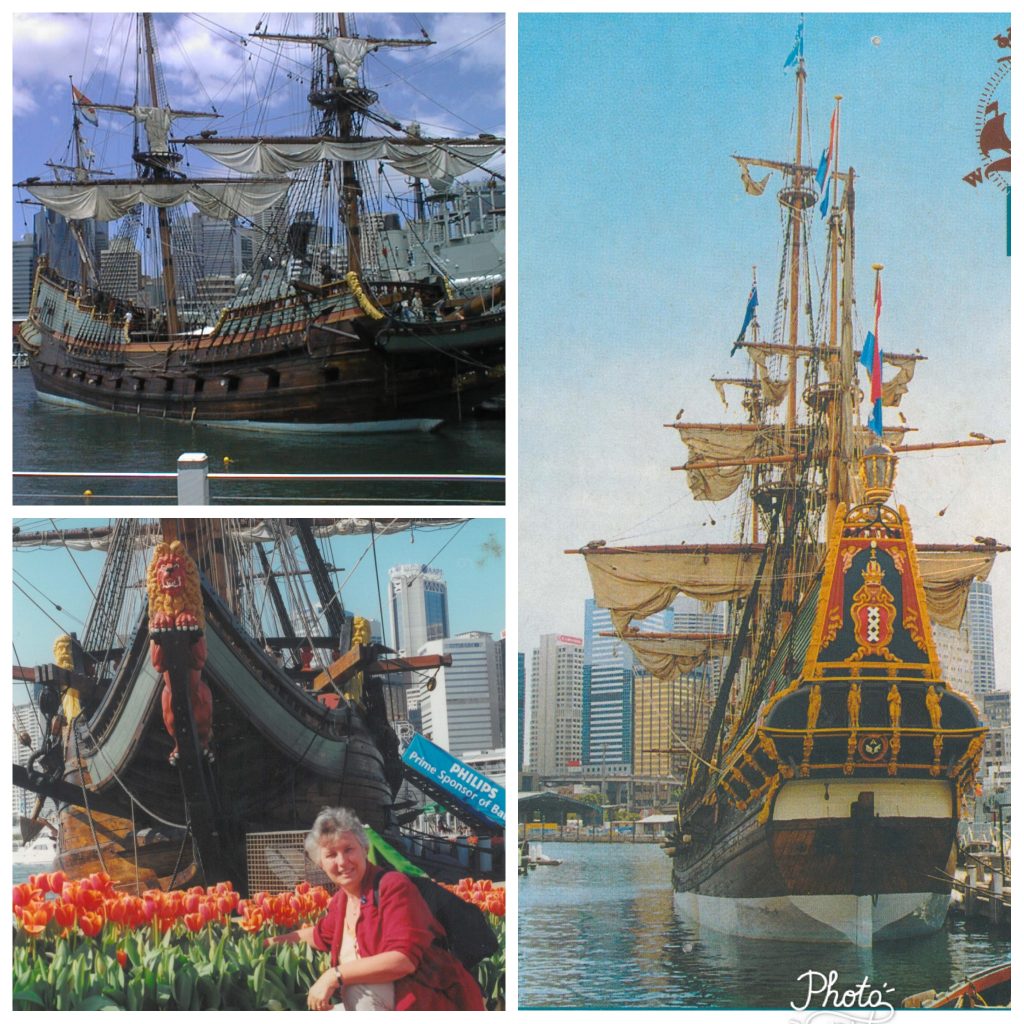

Below is an overview of the three groups of photos .

In 2000 the Batavia was transported by ship to Australia, where it took part in the celebrations surrounding the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. The photos in the group to the left are made at that time.

The photo in the middle depicts the large-scale embroidered work – known as the Batavia tapestry – by Melbourne textile artist Melinda Piesse. It was on display in the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney in 2017.

The group of four photos to the right shows pictures of the Houtman Abrohlos. All these pictures were made during a flight over the islands in 2018.

Top left: overview of the Pelseart Group of Islands, the southernmost of the three groups of islands that make up the Houtman Abrolhos island chain. It was here where the drama of the Batavia unfolded.

Top right: Morning Reef near Beacon Island where the Batavia was shipwrecked.

Bottom left: Beacon Island known as the Batavia Graveyard, it is here that most victims of Cornelisz were killed. There is currently archaeological works taken place in relation to the remains. For that purpose all fisherman’s huts that have build during the mid 1900s have been removed from the island.

Bottom right: Long Island. Pelsaert decided to conduct his trials on the islands, because the Sardam on the return voyage to Batavia would have been overcrowded with survivors and prisoners. After a brief trial, the worst offenders were taken to Seal Island (now called Long Island) and executed. Cornelisz and several of the major mutineers had both hands chopped off before being hung. Bottom right: Gun Island

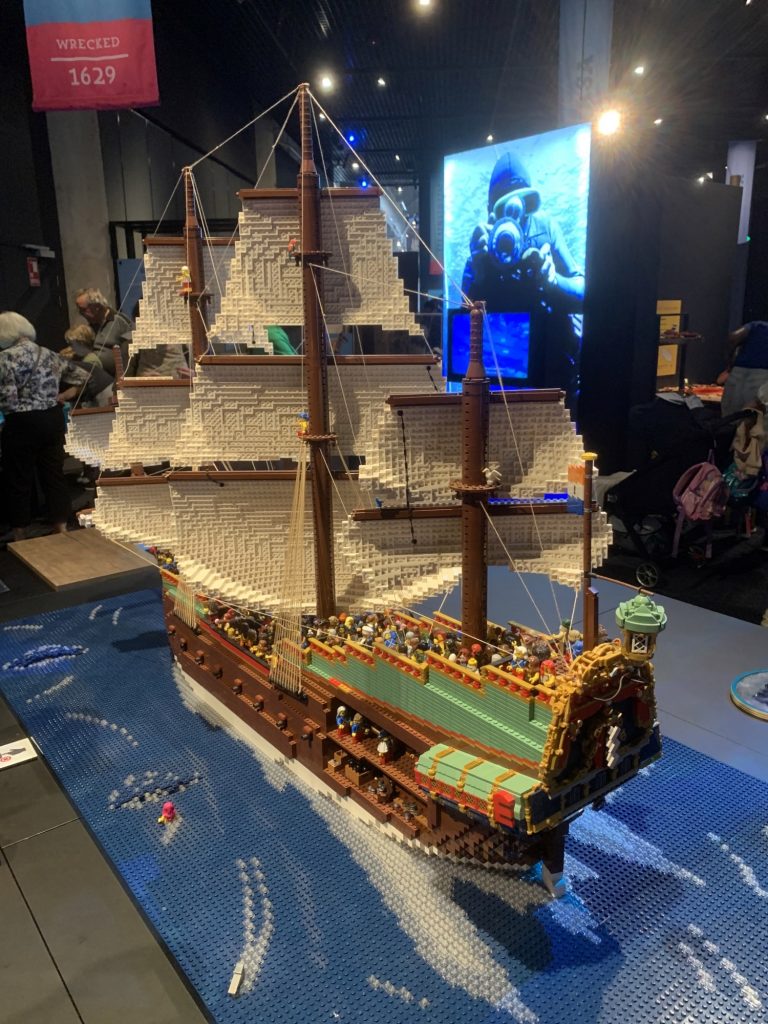

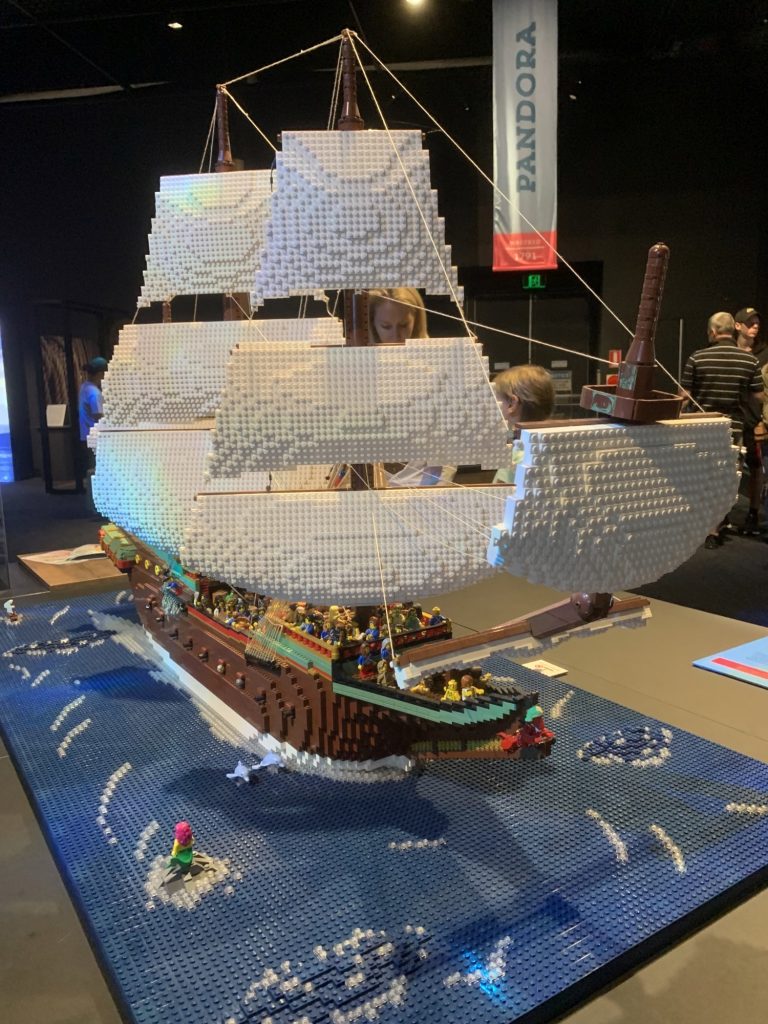

The pictures below were made by Roland Spuy at the lego exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in Sydney in January 2023.

The Houtman Abrolhos Islands

In 2018 we flew to Geraldton and from here we toured the Shipwreck Coast to Dirk Hartog Island to the north. We flew over the Pelsaert Group of islands where the drama with the Batavia happened. Geraldton has an excellent museums with a large section dedicated to the Batavia and other shipwrecks. Batavia Park, dedicated to people who died in the massacre was opened in 2013, 50 years after the discovery of the wreck by Max Weber.

Paul Budde – 2018 (all pictures are made by me)

New research challenges the Batavia mutiny narrative

For centuries, the Batavia shipwreck has been synonymous with one of history’s most shocking mutinies. However, new research suggests we may have misunderstood the causes of the massacre that followed. In a recent article published in the International Journal of Maritime History, Dutch cultural psychologist Jaco Koehler offers an alternative interpretation that challenges the long-standing view of Jeronimus Cornelisz as the sole architect of a brutal reign of terror.

Reinterpreting the Batavia Massacre: From Mutiny to Moral Collapse

The 1629 shipwreck of the Batavia off the Western Australian coast is one of the most infamous maritime disasters in Australian history. Traditionally, the tragedy has been told as a tale of calculated evil: Cornelisz, a heretical and power-hungry under-merchant, allegedly led a brutal mutiny that resulted in the murder, rape, and execution of over 100 men, women, and children marooned on the Houtman Abrolhos Islands. This narrative, preserved largely through the journal of commander Francisco Pelsaert, has gone unquestioned for centuries and continues to inspire popular media. However, Koehler argues that the accepted version is shaped by confirmation bias, a flawed judicial process, and confessions obtained under torture.

According to Koehler, the mass violence was not orchestrated by a single deranged villain but was a chaotic response to extreme conditions: starvation, dehydration, fear, and the absence of leadership following Pelsaert’s departure to seek rescue. He posits that a social collapse, not a premeditated conspiracy, triggered the atrocities—a spontaneous descent into savagery among desperate individuals, rather than a plot driven by one man’s ambitions.

This thesis is contested by leading archaeologists, including Professors Alistair Paterson and Wendy van Duivenvoorde, who are involved in ongoing excavations on Beacon Island. Their work confirms the scale of the violence but casts doubt on famine as the primary driver. They question why survivors, if motivated by survival, did not move to resource-rich islands nearby or follow smoke signals sent by others who had found food and water.

Nonetheless, Koehler’s analysis reopens a critical conversation about how we interpret historical violence and the psychological forces at play in moments of extreme crisis. By reframing the Batavia story as a collapse of social order rather than a conspiracy of evil, his work challenges us to reconsider how societies behave when stripped of authority, resources, and hope.

The Batavia wreck and the mass graves on Beacon Island remain an ongoing source of archaeological and historical inquiry. As new evidence emerges, Koehler’s theory—though not universally accepted—reminds us of the need to critically examine our sources and remain open to evolving interpretations of even the most established historical events.

See: Madness, murder and rape on the Batavia: new theory on Australia’s most horrific shipwreck

Batavia the opera

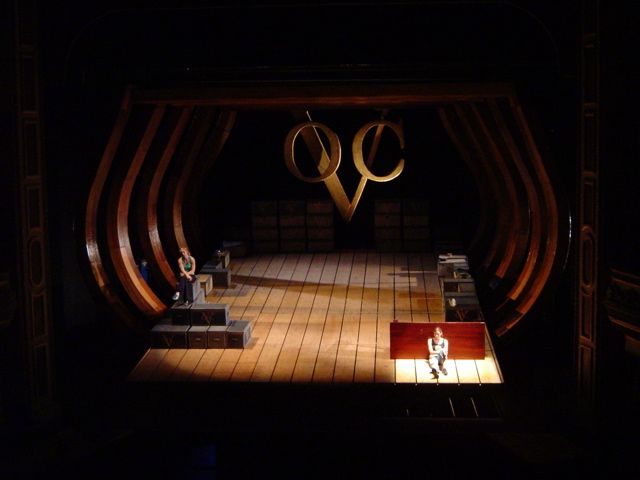

The drama of the Batavia has been transformed into an opera. It is in three acts and a prologue by Richard Mills to a libretto by Peter Goldsworthy, commissioned by Opera Australia. The plot is based on the historical events surrounding the Dutch sailing ship Batavia.

The opera premiered on 11 May 2001 at the State Theatre (Melbourne) for the Centenary of Federation Festival. It received three Helpmann Awards and six Green Room Awards. The work lasts for about three hours and ten minutes with one interval. Pictures below are scenes for the opera.

Het beest uit zee, de ondergang van het Compagnieschip Batavia

(The Beast from the Sea, the Downfall of the Company Ship Batavia) by Anthony van Kampen

The Dutch author Anthony van Kampen wrote the book titled: “Het beest uit zee, de ondergang van het Compagnieschip Batavia” (1971). The title translates to “The Beast from the Sea, the Downfall of the Company Ship Batavia.” The book explores the historical events surrounding the shipwreck of the Batavia, a Dutch East India Company (VOC) ship, in 1629.

Anthony van Kampen’s book delves into the details of the shipwreck, the subsequent events on the islands, and the rescue of the survivors. It provides a gripping account of the tragedy, drawing upon historical records and firsthand accounts to recreate the dramatic story.

See: Books about Mary Bryant and the Batavia from Anthony van Kampen

TV Drama that never was……

In 2011 Screentime acquired the rights to Peter FitzSimons’ bestseller Batavia, to become a six-hour miniseries on 10. Based on the historical events of 1629 when a Dutch merchant ship foundered off the coast of Western Australia, Batavia promised sea-faring adventure, the battle of good versus evil, mutiny, shipwreck, love, lust, criminality, a reign of terror, sexual slavery, natural nobility, survival, retribution, rescue and the birth of the world’s first corporation. 10 confirmed the series would set sail into production in 2013, to film interiors in Canada and exteriors in Queensland, but Screentime was unable to finance in a desirable timeframe. 10 did not rule out revisiting it further down the track, but so far, no land ahoy.

See: https://tvtonight.com.au/2023/12/tv-dramas-that-never-were.html.

Others articles on the Batavia in the DACC collection

Below is a collection of video talks and other stories about the Batavia.

Wreck of the Batavia brought back to life in forensic reconstruction by Flinders University

Dirk Drok and the discovery of the Batavia

Anthropological analyses of human skeletal remains associated with the Batavia Mutiny

SBS Video – Peter FitzSimons at SBS Radio/Dutch about his book Batavia 29-3-2011

SBS Video – Peter FitzSimons on SBS Radio about the Batavia’s significance 5-4-2011

SBS Video – Peter FitzSimons Talks Batavia 5-4-2016

Graf met opvarenden Batavia gevonden 3-11-2017

Batavia research at Flinders University Archaeology

Scheepswrak ‘Batavia’ onthult geheimen van 17de-eeuwse scheepsbouw.