In reviewing the article Ripples of Decolonisation in the Asia-Pacific by Charles Hawksley and Rowena Ward (2019), I was struck by how closely its themes intersect with lesser-known Dutch–Australian wartime and postwar connections. While the article does not focus on Dutch-Australian relations per se, it provides valuable context for understanding how the Netherlands’ decolonisation of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI)—modern-day Indonesia—also shaped Australian diplomacy, migration, and regional engagement.

A key point made by Hawksley and Ward is that decolonisation across the Pacific was neither straightforward nor uniform. In the Dutch case, this complexity is evident in their postwar effort to retain control of West Papua, even as sovereignty over the rest of the Netherlands East Indies was transferred to the Republic of Indonesia in 1949. The authors discuss how Indonesia’s eventual takeover of West Papua—through the highly contested 1969 “Act of Free Choice”—was largely accepted by the UN and the US as inevitable, despite clear evidence that the process was flawed and did not reflect the true will of the Papuan people. Australia, as the administering power in neighbouring New Guinea under a UN trusteeship, was directly positioned within this regional decolonisation process.

I have a personal connection to this history. My aunt, Annie Budde, worked as a teacher in Merauke and Tanah Merah during the final years of Dutch colonial administration. She was forced to leave when Indonesian forces moved in. She spoke passionately about the injustice done to her beloved Papuan community—people she had lived and worked with for years. I interviewed her in 2004, and she urged me: “Tell them how things are now.” I later published her story in Dutch, and at her request, included the following dedication:

“Dedicated to the proud people of the Papuans, in the firm belief that one day they will be able to determine their own lives and their own future. I hereby express my full support for an independent West Papua.”

There’s another important Dutch–Australian link that deserves more attention: the Australian Waterside Workers’ Federation once again refused to load Dutch navy vessels bound for New Guinea during the West Papua conflict. Just as they had supported Indonesian independence in the late 1940s by boycotting Dutch ships, Australian wharfies again expressed solidarity—this time with the Papuan people—by disrupting Dutch military logistics. These acts of defiance show how Australia’s involvement in the region wasn’t limited to diplomacy or military policy, but also played out on the docks through trade union action and public protest.

Yet, despite these gestures, union influence was not strong enough to shift national policy. Australia, like other Western powers, ultimately fell in line with the geopolitical reality of Indonesia’s control over West Papua. The right of Papuans to genuine self-determination was sidelined, and their voices ignored. The wharfies’ protests were a moral stand, but they could not overcome the political inertia that allowed a flawed decolonisation process to proceed.

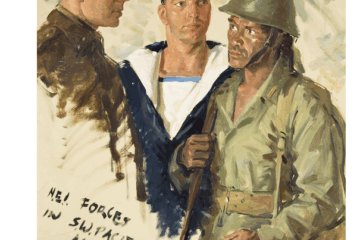

What the article does not mention—but what is vital from a Dutch-Australian perspective—is the role of Camp Columbia in Brisbane during World War II. This site served as the headquarters of the NEI government-in-exile. With the support of the Australian and American governments, Dutch forces used the camp to prepare for the recolonisation of the Netherlands East Indies after Japan’s surrender. Far from planning a transition to Indonesian independence, Dutch officials initially hoped to reassert colonial authority—an ambition that soon clashed with the emerging Indonesian nationalist movement. This underlines how Australia was not just a bystander but a host and enabler of Dutch postwar planning, even as it would later shift towards supporting Indonesian sovereignty.

This connection to Camp Columbia underscores a broader point made implicitly in Hawksley and Ward’s work: that decolonisation was not just a matter of military withdrawal, but of clashing visions of sovereignty, often played out in third-party countries like Australia. It also helps explain why so many Dutch migrants—especially those with ties to the NEI—resettled in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, bringing with them layered identities shaped by colonial displacement, war, and political upheaval.

By revisiting this scholarly article through a Dutch-Australian lens, we can better appreciate how local stories—such as those linked to Camp Columbia—fit into much larger global transformations. It reminds us that Dutch-Australian history is not confined to migration and settlement alone, but is deeply entangled in the postwar struggle over empire, independence, and regional power.

Ripples of Decolonisation in the Asia-Pacific is included below for readers interested in the broader regional context.

Paul Budde

Reference:

Hawksley, C. & Ward, R. (2019). Ripples of Decolonisation in the Asia-Pacific. PORTAL Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, 16(1–2), 1–10.

DOI: 10.5130/portalv16i1-2.6824