In the final years of Dutch administration in New Guinea, the Netherlands and Australia sought to establish a common development policy across the island. These conferences, held between 1959 and 1960, symbolised an ambitious vision of regional cooperation in health, education, infrastructure and administration. Yet they were also shaped by the political realities of decolonisation, Indonesian pressure, and the shifting priorities of Australia and its allies. The initiative was as much about strengthening Dutch legitimacy in the territory as it was about genuine collaboration, and ultimately it was overtaken by the larger forces that led to the transfer of sovereignty to Indonesia in 1962.

Historical and geopolitical background

After the transfer of sovereignty over most of the Dutch East Indies to Indonesia in 1949, the Netherlands retained control of western New Guinea (later called Nederlands-Nieuw-Guinea). The Dutch argued that Papuans possessed a distinct identity and required time to build the institutions of self-government.

Australia, meanwhile, governed the eastern half of the island as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. Canberra regarded developments in New Guinea as vital to its security and to the stability of Melanesia. Both powers therefore faced similar challenges of administration, development and international legitimacy.

The dispute with Indonesia heightened the urgency. From the mid-1950s onward, Jakarta pressed its claim to the territory with increasing vigour. The Dutch response was to emphasise their commitment to Papuan development, and an agreement with Australia on a coordinated policy would provide powerful evidence of that commitment.

The rationale for cooperation

By the late 1950s it was clear that issues such as health, communications, education and migration could not be neatly confined to one half of the island. The Dutch saw the value of working alongside Australia, which had long experience in governing Papua and New Guinea. For Australia, closer ties with the Dutch could bolster regional stability and demonstrate its own capacity to work with European partners in the Pacific.

Thus emerged the idea of a gemeenschappelijke ontwikkelingspolitiek — a common development policy — that could align objectives, reduce duplication and strengthen each administration’s credibility.

The Schakels publication, 1959

In 1959 the Dutch Ministry of Internal Affairs published a special issue of its information series Schakels titled Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea en de Nederlands-Australische samenwerking. This booklet signalled to the public and to international observers that the Netherlands was committed to cooperation with Australia in the development of New Guinea. It highlighted the areas in which joint action was seen as possible: administration, infrastructure, public health and education.

The first conference, Canberra 1959

The first formal step was the “Eerste conferentie betreffende Australisch-Nederlandse administratieve samenwerking in Nieuw-Guinea,” held in Canberra on 28 April 1959. Dutch and Australian officials met to explore how their administrative systems might be harmonised and to exchange experiences in governing difficult terrain with limited resources. While the surviving documentation is sparse, it appears that the Canberra meeting set the stage for more ambitious talks to follow.

The Hollandia conferences, March 1960

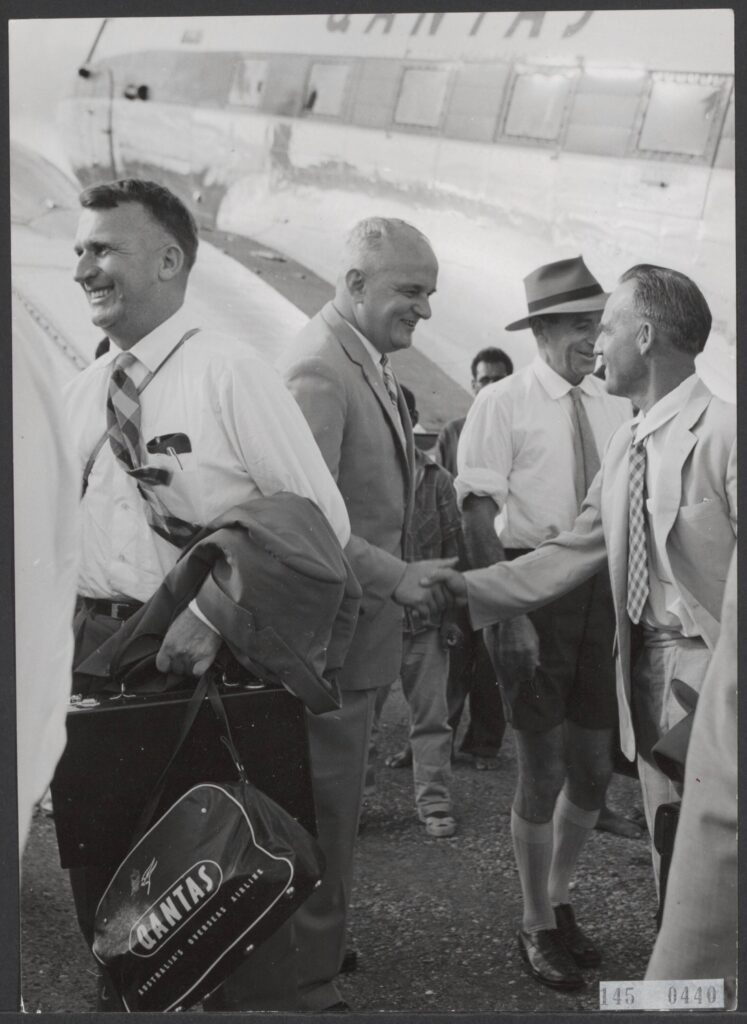

Description: Conference on Dutch–Australian cooperation in New Guinea. Arrival of the Australian delegation at Sentani airfield near Hollandia on 3 March of this year. The Director of Internal Affairs, A. Boendermaker (centre), warmly welcomes the members.

Date: 3 March 1960

The most visible event in this process was the conference convened in Hollandia in March 1960. Photographs show the Australian delegation arriving at Sentani Airport on 3 March, greeted by Dutch officials including Director of Internal Affairs A. Boendermaker. A formal opening session was held with Governor P. J. Platteel delivering a keynote address.

The conference attracted attention beyond the region. A British Pathé newsreel, captioned “Dutch and Australian experts hold cooperation conference,” recorded the proceedings, underlining their international significance. Dutch news publications also featured images of the sessions, giving the impression of a serious bilateral undertaking.

There is also a short video of the arrival of the Australian delegation.

Areas of proposed cooperation

While no comprehensive set of minutes has been traced, the scope of the talks can be reconstructed from contemporary sources and the policy context of the time. Major domains included:

- Administration and governance: cooperation in training civil servants and sharing expertise in local administration.

- Infrastructure: coordination in building roads, airstrips and communication networks, essential for connecting remote areas.

- Health services: joint strategies for combating tropical diseases, vaccination campaigns and medical training.

- Education: the development of teacher training, curricula and technical education for Papuans.

- Agriculture and rural development: sharing research in crop production and settlement schemes.

- Survey and mapping: collaboration in geographical surveys and demographic studies.

These areas reflected the practical challenges both administrations faced in a difficult environment, as well as the broader aim of presenting Papuan development as a shared regional responsibility.

Constraints and challenges

Despite the enthusiasm, the scheme faced significant limitations. Sovereignty was a constant sensitivity: neither side could appear to compromise territorial authority. The Dutch were eager to present the cooperation as proof of their rightful presence, while the Australians had to balance relations with Indonesia and with allies such as the United States and Britain.

Administrative structures were also different. Dutch New Guinea was an overseas territory of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, while Papua and New Guinea was an Australian trust territory under the United Nations. Legal frameworks, budgetary processes and political accountability varied widely.

Above all, international politics constrained the project. By 1962, under intense pressure from the United States and the United Nations, the Netherlands agreed to transfer the territory first to a UN interim administration and then to Indonesia. Australia itself adjusted its stance, moving towards acceptance of Indonesian sovereignty as part of a broader regional settlement.

Legacy and significance

The Dutch–Australian conferences on a common development policy were overtaken by the pace of international diplomacy. Yet they remain significant as a demonstration of how colonial and territorial powers sought to translate development rhetoric into regional cooperation. The vision of bridging the border through practical measures was ambitious, but it was also bound to the declining Dutch position in New Guinea.

The cooperation provided the Dutch with short-lived diplomatic capital, showing international audiences that they were not acting in isolation. For Australia, it was an exercise in cautious engagement, reflecting both its practical interests in the development of New Guinea and its delicate balancing of international relationships.

Ultimately, the conferences of 1959–60 highlight the paradox of colonial development at the end of empire: ambitious plans, careful diplomacy, and real technical expertise, but all overshadowed by the irresistible momentum of decolonisation.

Afterword

It remains a sad story that the Papuans of the former Dutch territory were never granted independence or even semi-independence. After the transfer of sovereignty in 1962, Indonesia actively promoted transmigration, particularly from Java, and today many Papuans find themselves as second-class citizens in their own land. With sustained Dutch–Australian cooperation, the outcome might have been very different. Papua New Guinea gained independence in 1975, and a continued partnership between the Netherlands and Australia across the whole island could have offered the Papuans of the west a much stronger foundation for self-determination.

This history is also personal to me. My aunt, Annie Budde from Ootmarsum, worked as a teacher in Merauke and Tanah Merah during those years. She was forced to leave in 1962, but throughout the rest of her life she actively supported the independence of her beloved Papuans. I have written elsewhere (in Dutch) about her experiences in Dutch New Guinea, which remain a poignant reminder of what was lost when the chance for Papuan self-rule was foreclosed.

Paul Budde October 2025

See also:

Defining a frontier: Dutch–Australian border cooperation in New Guinea, 1954–1960

The Dutch Resident of Merauke visits Australian Papua New Guinea

Piet Merkelijn: bridging the Netherlands, Australia and Dutch New Guinea

Training Dutch officers in Australia for the Netherlands Indies and Papuan development

Sources:

Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw Guinea 1945-1962 . – A key Dutch-language scholarly work on governance in Dutch New Guinea, which mentions the Dutch–Australian conferences and the idea of a “gemeenschappelijke ontwikkelingspolitiek.”