From 1947 to 1962, the Netherlands and Australia both belonged to the same regional organisation, the South Pacific Commission (SPC). The Commission was created by the Canberra Agreement of 1947, signed by six administering powers with dependent territories in the Pacific: Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, France, the United States and the Netherlands. Each represented its colonial or trust territories— for the Netherlands this was Netherlands New Guinea, and for Australia, the Territory of Papua and New Guinea.

A post-war vision for the Pacific

The SPC was conceived in the aftermath of the Second World War as a body for regional development and welfare. Its purpose was not political independence but cooperation in health, education, agriculture, and economic and social advancement. Member governments pooled technical expertise, and conferences were held every three years at rotating Pacific venues such as Suva, Nouméa and Pago Pago.

Through its participation, the Netherlands positioned Netherlands New Guinea as a Pacific territory, distinct from the rest of the former Netherlands East Indies. The Dutch hoped this would help the territory develop along Melanesian rather than Indonesian lines. Australia supported Dutch membership, as it aligned with Canberra’s vision of regional collaboration among Western-administered Pacific territories.

Founding members of the South Pacific Commission (1947–1962)

| Administering Power | Territories Represented |

|---|---|

| Australia | Papua and the Territory of New Guinea |

| New Zealand | Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Western Samoa |

| United Kingdom | Fiji, Solomon Islands, Gilbert and Ellice Islands, others |

| France | New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna |

| United States | American Samoa, Guam, Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands |

| The Netherlands | Netherlands New Guinea |

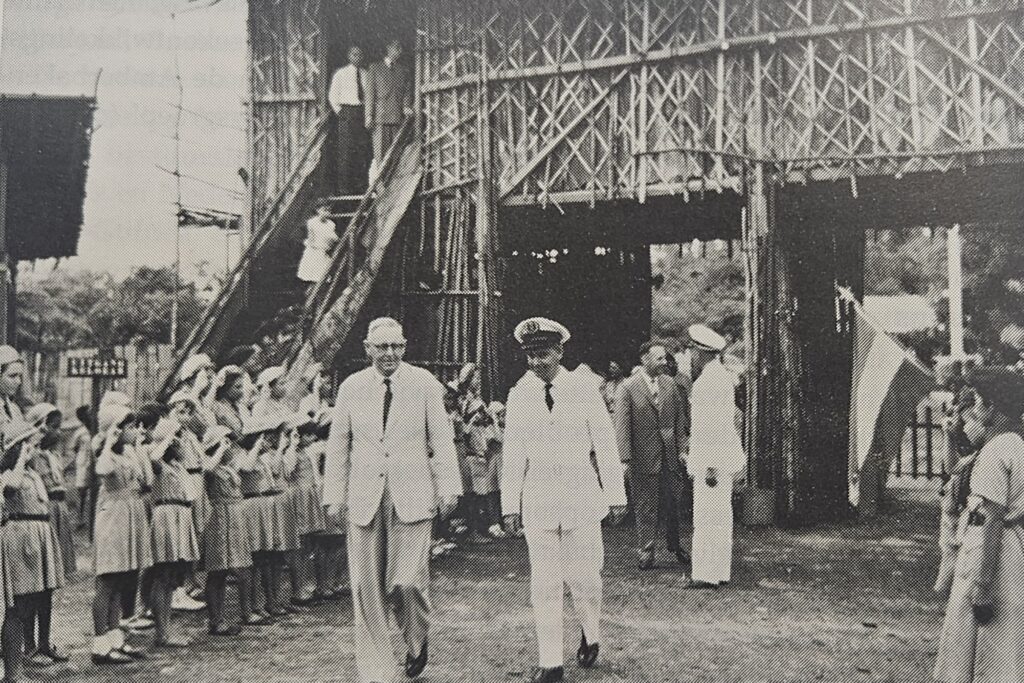

The 1950 South Pacific Conference

The first South Pacific Conference was held in Suva, Fiji, in 1950. It marked the first time that representatives of Netherlands New Guinea joined their counterparts from other Pacific islands. Among the Dutch administrative staff involved was Piet Johannes Merkelijn, then working in the Department of Civil Information (Bevolkingsvoorlichting).

Merkelijn later recalled that preparing for the Conference was a very labour-intensive task. His team translated all the Commission’s papers into Indonesian so that Papuan delegates could study and discuss them in advance. These papers covered the SPC’s work programmes and budgets across health, economic and social fields. When the study meetings proved successful, Merkelijn’s service also translated documents from the New Guinea Council (Nieuw-Guinea Raad).

He wrote that the Papuan delegates—men and women alike—made valuable contributions to the debates despite the language barrier. Members of the Bevolkingsvoorlichting department provided simultaneous translation of English speeches into Indonesian during the sessions, a process he described as exhaustingly difficult.

For many future members of the New Guinea Council, participation in the South Pacific Conferences became an important part of their political education. Merkelijn remembered one delegate, Nicolaas Jouwe, turning to him on the flight home and saying enthusiastically, “This is life!”

Nicolaas Jouwe would later become one of the leading figures in the Papuan independence movement. After the transfer of Netherlands New Guinea to Indonesia in 1962, Jouwe went into exile in the Netherlands, where he continued to advocate for Papuan self-determination for decades. His participation in the South Pacific Conferences had given him an early experience of international diplomacy and contact with other Pacific island leaders—formative influences on his later political work.

Regional cooperation and Australian connection

During the twelve years that both countries were members of the South Pacific Commission, the Netherlands and Australia worked closely together. Their representatives sat side by side in technical committees and at the regional conferences, sharing knowledge about tropical agriculture, disease control, and education systems. Both also sought to showcase their administrative achievements in their respective New Guinea territories.

While Dutch participation ended in 1962 with the transfer of Netherlands New Guinea to Indonesia, the collaboration left a legacy of professional links and shared development ideas. Australia remained a leading member of the organisation, while the Netherlands’ withdrawal marked the end of its presence in Pacific regional affairs.

Legacy

The South Pacific Commission, now known as the Pacific Community (SPC), continues to this day, Australia is still a member. it is headquartered in Nouméa. Between 1947 and 1962, its membership embodied the colonial geography of the Pacific, but it also created one of the earliest forums where indigenous leaders from across Oceania could meet and exchange ideas.

Through the work of administrators like Piet Johannes Merkelijn, the Netherlands ensured that Netherlands New Guinea had a voice in that regional dialogue. His recollections remind us that the experience of participating in these conferences helped shape a generation of Papuan representatives and symbolised a moment of genuine Dutch–Australian partnership in the Pacific.

Paul Budde October 2025

See also:

Defining a frontier: Dutch–Australian border cooperation in New Guinea, 1954–1960

The Dutch Resident of Merauke visits Australian Papua New Guinea

Piet Merkelijn: bridging the Netherlands, Australia and Dutch New Guinea

Training Dutch officers in Australia for the Netherlands Indies and Papuan development

Source:

Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea 1945–1962

Report to the first South Pacific Conference, Suva, April-May 1950