In September 1945, as Japan’s capitulation brought the Second World War to an end, Australia was tasked with overseeing the surrender of tens of thousands of Japanese troops scattered across the islands of New Guinea and the Netherlands East Indies. These operations were not limited to Australian territories. In neighbouring Dutch New Guinea, Australian forces, acting in cooperation with Dutch authorities, conducted a series of formal surrenders that closed the Pacific War’s final chapter.

The final phase of the New Guinea campaign

The war in New Guinea had been among the longest and most gruelling in the Pacific. By 1945, Japanese forces were isolated in pockets across New Guinea, New Britain and the Moluccas. Although the Emperor’s broadcast of 15 August 1945 had announced Japan’s surrender, many local commanders refused to yield until Allied officers arrived to receive their formal capitulations.

For the Australian Army and the Royal Australian Navy, this required a coordinated series of surrender expeditions along the New Guinea coast. The Rabaul ceremony on 6 September 1945, where General Hitoshi Imamura and Vice-Admiral Jinichi Kusaka surrendered all Japanese forces in the South-West Pacific to General Vernon Sturdee, was the symbolic endpoint. But the practical work continued for weeks. Each Japanese garrison had to be approached, disarmed, documented and repatriated—an immense logistical task involving ships, interpreters and civil administrators.

Vogelkop Force and the Dutch New Guinea coast

Responsibility for the western end of New Guinea, including Dutch territory, fell to Vogelkop Force, an Australian command group operating under the New Guinea Force. Its naval component was centred on the Royal Australian Navy survey ship HMAS Lachlan, which was temporarily reassigned from hydrographic duties to transport surrender parties and oversee disarmament.

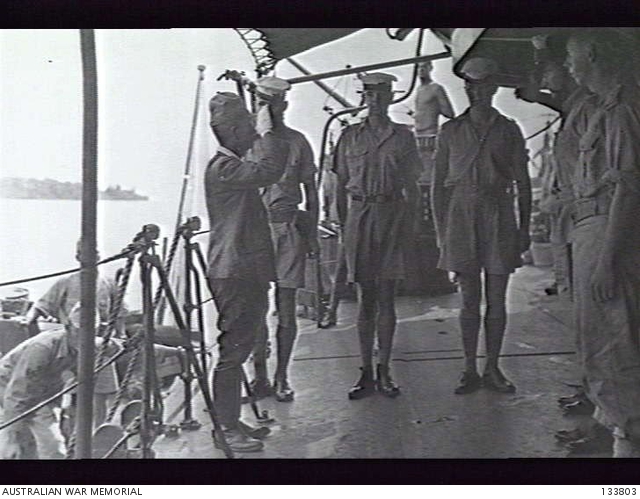

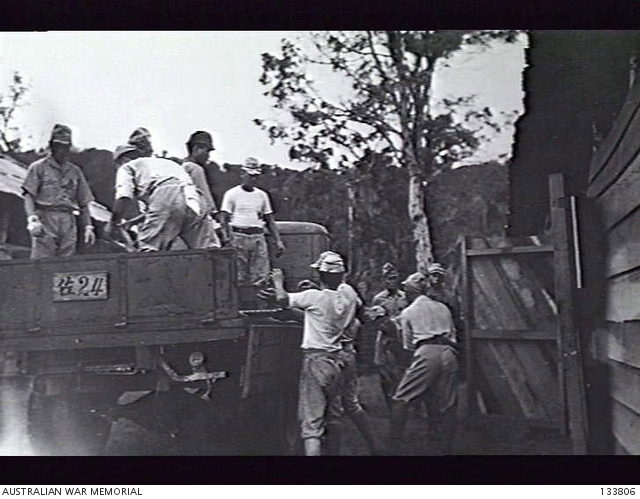

Photographs held by the Australian War Memorial (AWM) document HMAS Lachlan’s role in these operations. At Manokwari, Colonel Suzuki, the Japanese commander, is shown coming aboard the ship to present surrender papers. In Sorong, General Ikeda and his staff are pictured disembarking from Japanese barges alongside Lachlan to attend the surrender conference. Other images show Japanese soldiers stacking weapons and ammunition under Australian supervision and local Papuans observing the proceedings from the shore.

These operations were not merely ceremonial. They were accompanied by Australian Army and RAAF detachments who documented war crimes, inspected prisoner-of-war camps, and coordinated medical and logistical support. The official record War Crimes and Trials – Surveillance visit to Dutch New Guinea, Sarmi, Manokwari, Sorong, 1945 confirms that Australian patrols visited each of these sites in sequence.

Pictures below made after the Japanese surrender at Manokwari in September 1945 are from the Australian War Memorial and are donated to them by Lieutenant Colonel J. W. London

Dutch representatives at the surrender ceremonies

Although most Australian military records focus on Australian and Japanese participants, Dutch sources and postwar reports confirm that representatives of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) were also present at the surrender ceremonies. At Manokwari, NICA officials had already resumed control in 1944 under Australian protection, and Dutch officers were most likely on board HMAS Lachlan during the surrender of Colonel Suzuki’s garrison. At Sorong, where Dutch and Australian personnel had shared authority since mid-1944, the formal surrender was described as conducted “in cooperation with Dutch authorities.”

At Sarmi, Dutch participation is explicitly documented. Among those landed by Australian ship to witness the surrender was the young NICA officer Piet Johannes Merkelijn, whose later account provides rare first-hand insight into the event and the re-establishment of Dutch administration that followed.

Pieter de Kock and the Papuan Battalion

Another key Dutch participant at Sarmi was Pieter Petrus de Kock (born Ambon, 1918). At the outbreak of the war, de Kock served in the KNIL and was stationed at Manokwari. When the Japanese invaded in 1942, he joined Captain Geerooms Willemz’s guerrilla force, which retreated into the mountains and fought on for three years. Of the sixty-six men in the original unit, only fourteen survived by August 1945.

After the liberation of Manokwari, de Kock joined the newly formed Papuan Battalion, commanding a company of about 150 men based at Sarmi. In October 1945—two months after Japan’s capitulation—he took part in the surrender of the local Japanese forces under General Tanoye. The Australian party, likely aboard HMAS Lachlan, conducted the formalities, while de Kock and his Papuan troops secured the area and supervised the transfer of control to Dutch hands.

The presence of both Merkelijn and de Kock at Sarmi symbolised the dual nature of the Dutch return to New Guinea: civil administration on one hand and Papuan-assisted security on the other. De Kock’s career continued after 1946 in the Binnenlands Bestuur (Internal Administration), where he served until 1962.

Rebuilding under Australian protection

At Sarmi, as elsewhere, the transition from war to peace was fragile. The town had been almost completely destroyed by Allied bombing and ground fighting. The small Dutch administrative team improvised its offices from salvaged materials, lighting them at night with bottles filled with aviation fuel. Despite the hardship, Sunday services were held, and the first tentative steps toward normal life resumed.

The Australian presence along the coast ensured stability during this period. By securing the surrender of all remaining Japanese units, the Australians created the conditions under which Dutch civil government could return. The cooperation between the two nations in 1945 thus bridged the wartime alliance and the post-war administrative partnership that continued until Dutch New Guinea was transferred to Indonesia in 1962.

A shared conclusion to war

The Australian surrender expedition across New Guinea was one of the most extensive logistical undertakings of the immediate post-war period. It combined naval precision, humanitarian oversight, and coordination with Allied civil authorities. In Dutch New Guinea, it carried additional political meaning: a moment when Dutch and Australian officers stood side by side to close a war that had engulfed both nations’ colonial territories.

The events at Sarmi stand as a particularly vivid example of this cooperation. They mark both the physical end of Japanese occupation and the symbolic restoration of civil governance under Dutch–Australian partnership—a fitting conclusion to the shared wartime experience in the Pacific.

Paul Budde October 2025

Research note

Key sources:

Australian National Archives, Instrument of Surrender of all Japanese Armed Forces in Papua and New Guinea, Canberra, 1945.

Piet Johannes Merkelijn, Eerste bestuursimpressies uit de onderafdeling Sarmi, in Besturen in Nederlands Nieuw Guinea 1945-1962 (Leiden, KITLV Press, 1996).

Dutch biographical entry on Pieter Petrus de Kock, Papua Erfgoed / Nieuw-Guinea Institute.

Reports of Proceedings – HMAS Lachlan, 1945–49, Royal Australian Navy archives.