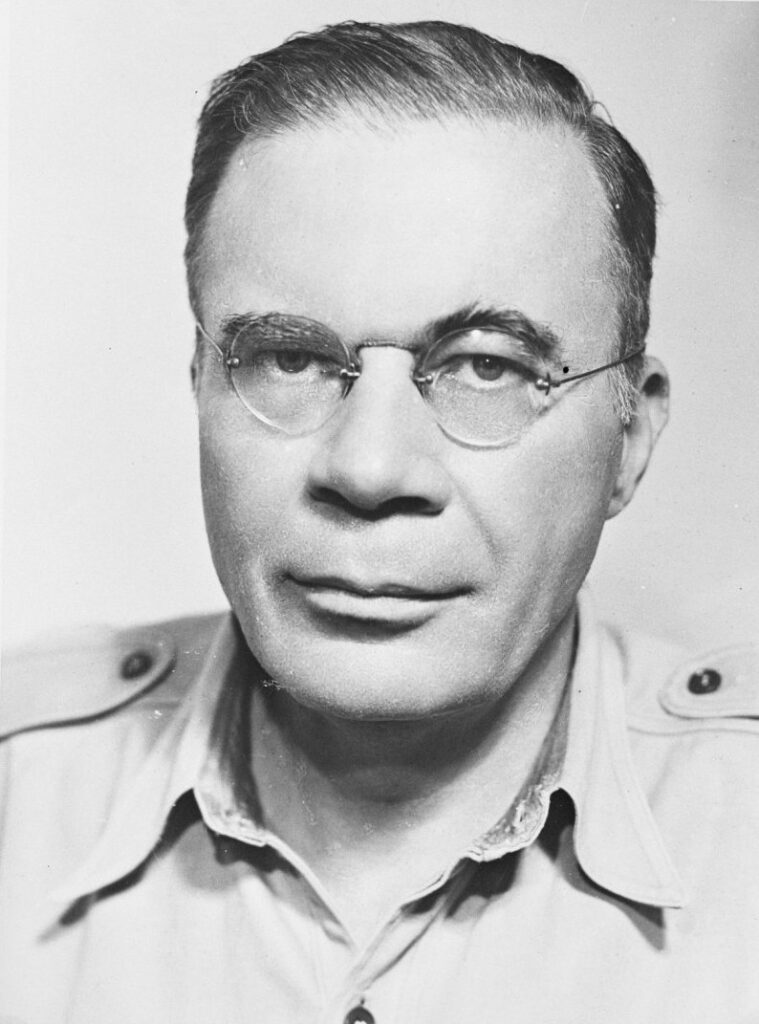

Hubertus Johannes van Mook (1894–1965) was one of the most significant and controversial Dutch administrators of the Second World War and its aftermath. Born in Semarang, Java, Van Mook was part of the Indo-European community of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI), whose families had lived in the archipelago for generations. This background gave him a deep familiarity with Indonesian society and shaped his later push for reform and a postcolonial future for the region.

During the early stages of the war, Van Mook served as Director of Economic Affairs in the NEI government. After the Japanese invasion in early 1942, he was sent to Australia as lieutenant governor-general of the Dutch East Indies to assist in coordinating Dutch operations in exile. Though his time in Australia was brief, Van Mook still played a significant diplomatic role. He liaised with the Curtin government and attempted to secure recognition and support for the continued legitimacy of Dutch administration over the Netherlands East Indies. His diplomatic work occurred at a time when Australia was shifting its foreign policy focus away from Britain and toward more direct regional engagement, including with the exiled governments of the Netherlands and others.

However, Van Mook’s independent approach and growing interest in postwar political reform raised concerns within the Dutch government-in-exile in London, particularly from Prime Minister Pieter Sjoerds Gerbrandy. Within months of his arrival in Australia, Van Mook was recalled to London and appointed Minister for the Colonies. Although the position carried formal authority, it effectively placed him under the close supervision of the more conservative and restoration-focused cabinet. This limited his direct influence over Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation and reduced his ability to pursue political reform for the Netherlands East Indies.

In 1944, after considerable political pressure and with growing Allied interest in regional postwar planning, Van Mook was permitted to return to Australia. This time he headed the newly established Netherlands East Indies government-in-exile, which operated from Brisbane. In this role, he worked closely with Allied military command and Dutch naval and air force leadership, while preparing plans for the postwar reconstruction of the NEI.

Van Mook advocated a federal political model for Indonesia. He envisioned a commonwealth-style structure that would allow for significant Indonesian autonomy while preserving Dutch ties. His proposals were influenced by Allied thinking, particularly in Australia and the United States, where there was increasing discomfort with European colonialism in Asia.

His reformist stance put him in ongoing conflict with the Dutch cabinet in London, which remained committed to the full restoration of colonial authority. Van Mook’s openness to negotiations with Indonesian leaders and his attempts to engage Australian and American diplomats on political reform were viewed as a threat by his own government.

Following Japan’s surrender in 1945, Van Mook returned to Indonesia as Lieutenant Governor-General and led Dutch efforts to reassert control. He was instrumental in Dutch participation in negotiations and military actions during the Indonesian National Revolution. Despite his attempts to implement a federal structure, the approach was rejected by both Indonesian republicans and political conservatives in the Netherlands.

By 1949, the Dutch were compelled to formally recognise Indonesian independence. Van Mook, disillusioned by the failure of his reform vision and alienated from political allies on both sides, resigned. He retired to France, where he lived in relative obscurity until his death in Nice in 1965.

Although he never published memoirs, Van Mook’s public statements reveal a reformist outlook born from his Indo heritage and his understanding of Indonesia as more than a colony. He remains a complex transitional figure: caught between the demands of empire and the inevitability of decolonisation, between loyalty to Dutch sovereignty and recognition of Indonesian nationalism.

His time in Australia, his role in the NEI government-in-exile in Brisbane, and his political conflict with the Dutch government in London place him at the centre of Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation and the contested path to Indonesian independence.

See also in this series:

- Reform or restoration? Political tensions over the future of the Netherlands East Indies during wartime exile.

- Wartime reform and Indonesian voices: Dutch–Indonesian political tensions in exile.

- From indifference to diplomacy: how the war transformed Dutch–Australian foreign relations

- The Dutch purchasing mission and wartime supply issues in Australia