After the Japanese invasion of Indonesia in 1942, the Dutch fled to Australia taking with them Indonesian soldiers, sailors, government officials and more.

The Dutch Government made a deal with the Australian Government which gave the Dutch extra-terrestrial rights over many Indonesian refugees, declaring several former army camps as Dutch territory.

A camp located in Casino was under the agreement Dutch territory and was named Camp Victory by the Dutch as initially, the Dutch expected to return after victory over the Japanese.

From December 1942, a few hundred Indonesian soldiers arrived in Casino as part of the Dutch Armed Forces Technical Battalion. The group came to be known as ”The Dutch Boys” or ”The Casino Boys”.These soldiers were paid, had permission to leave camp at the end of the day and were given other various privileges. This was different to the first lot of prisoners who were treated otherwise. (The book about ‘The Casino Boys’ can be found at the end of this article).

The first lot of prisoners detained at Camp Victory in 1942-1943 were merchant seamen, then followed by Netherlands East Indies political prisoners that came from Tanah Merah prison camp held in New Guinea. The third lot of prisoners included both soldiers and civilians that were either recruited into the Technical Battalion and trained in a variety of trades or were employed as guards.

After the war’s end, many prisoners became agitated at delays in deporting them and having their wages delayed.

With the proclamation of Indonesian independence on August 17, 1945, many of the Indonesians felt they could no longer serve under Dutch command. The Australian Union Movement, supporting independence, refused to allow the Dutch servicemen to be shipped to the East Indies.

The Dutch responded to this declaration by surrounding the camp with barbed wire fences, twenty-four-hour flood lighting and guards armed with tommy guns.

The Dutch colonial administration started jailing citizens who refused to serve with the Dutch armed forces. They chose Victory Camp to incarcerate them along with Indonesians who had been training as airmen. Suddenly the Dutch who had been training for war found themselves guarding former colleagues.

According to Dutch born Jack Dalmayer Relationships between the prisoners and their guards were relaxed. The Dutch Boys began to take part in the Casino social scene, seeing movies and playing sport.

Finally, near the very end of 1946, the camp was disbanded. The prisoners were taken by train to Brisbane and then loaded on boats. There is still debate today over whether the captivity of the prisoners was legal.

A personal note from Edmund Nyst:

Casino’s Camp Victory was a huge big tent camp. There were a few barracks for offices and amenities, but the men lived in tents. … The camp held the First Battalion of the Netherlands East Indies Infantry. It was made up mainly of what we now call Indonesians. They were all professional soldiers from the Nederlandsch Indisch Leger which had been the army in the Dutch East Indies before the Japanese invasion. They had last fought in Timor with the Australian before being evacuated to Australia in 1942. Now they were used in different theatres of war under General MacArthur. (Source: Edmund Nyst 2007 The Old Fellow’s War. New Holland: Chatsworth, NSW – p138)

Article by Ingeborg van Teeseling – 2 September 2022

One of the interesting, and largely unknown, stories about the Dutch in Australia has to do with their ownership of part of Casino, a town in NSW. It is a narrative with a nasty racist streak. When the war broke out, the Dutch also had a colony in Surinam, a country in the north of South America. They had been running it with slave labour and the whip but still, after being run by the Dutch since 1831, most people largely felt Dutch. So with the motherland under attack, 500 men put their hand up to help at the front. The Dutch Prime Minister really didn’t want ‘niggers’, he said, because that would upset white soldiers from South Africa, who were also fighting for The Netherlands. But beggars can’t be choosers, so in 1942 those men were transported to Australia for training at Casino, where the Dutch had set up a camp. After that, they were sent to the front, fighting the Japanese. Their treatment by the Dutch was appalling. They were paid in Japanese invasion money, that was worthless. While they were in Australia, they were not allowed on the street, because Casino had ‘no place for coloureds like you’, as their commander said. They had been promised a post-war job and even land but never received either. The Surinamese men were not even allowed medical care or social services, everything their white peers did receive. Even now they feel ‘neglected’.

But Casino’s Camp Victory, as the Dutch called it, wasn’t only a training camp. It also held prisoners of the Dutch. Long before the war started, Indonesians had been fighting for their independence. Many of their leaders had been arrested and locked up in camps in New Guinea and Timor, where the Dutch were in control. In 1943 and 1944, the Dutch managed to get them out of there and bring them to Australia. There they were locked up behind barbed wire in Casino, guarded by Dutch military men with Tommy guns. The rationale behind this move had been to prevent the Indonesians picking up arms against the Dutch on the side of the Japanese. The Dutch fully intended to take back their ‘overseas territory’, as they called it, after the war. So, to leave motivated freedom fighters to their own devices was not considered a good idea. The result was that a sleepy town in rural NSW suddenly was confronted with a camp with hundreds of political prisoners inside its borders.

On 18 August 1945, just after the Japanese had surrendered, Indonesia proclaimed its independence. In the camp at Casino, this news was received with great joy. The Indonesian soldiers and employees soon started to declare themselves free from Dutch command. Every day, more and more of them followed. The Dutch answer was to lock them up with the political prisoners. Obviously, everybody now wanted to go home. But the Dutch weren’t having any of it. Despite the fact the war was over, they court-martialled the soldiers and convicted them to incarceration of at least a year. The employees who refused service were either locked up too or deported (to Timor, not to Indonesia). The political prisoners were also not allowed out. More barbed wire was added and by 1946, 500 men were locked up inside. Of course, they didn’t take that lying down. They wrote letters to the Australian Prime Minister Curtin. They went on hunger strikes, they organised protests. In September 1946, one of those got out of hand. The Dutch soldiers started shooting at the prisoners. Hundreds of machine gun rounds were fired, leaving one man dead, with 13 bullet wounds to his body. The Australians were powerless to do anything. The extra-territoriality they had given the Dutch meant that the Dutch were in charge of part of an Australian town.

But it would get more complicated. After the Indonesian proclamation of independence, a lot of Indonesians in Australia started to pressure the Dutch government to recognise their new nation. The irony was that a lot of those people were those ex-employees of the Dutch and ex-soldiers, brought to Australia a few years before. Part of them they were in Casino but hundreds were outside and started agitating for freedom. Most of them, despite their centuries of experiences with harsh Dutch rule, had hope that this time they would get their country back. That hope was based on a document that had been signed by all the Allied forces during the war. In 1941, they had developed the so-called Atlantic Charter. One of the promises in that Charter, was that after the war people would be able to choose their rulers. It was an important document, that would eventually be the foundation piece of the Declaration of Human Rights for the new United Nations. On the basis of the Charter, the Indonesians thought that their independence would be recognised immediately. But they were wrong. Almost straight after the Japanese surrender, the Dutch started their ‘police actions’, as they called them. Soon that turned into a full-scale war, with 100,000 dead at the end of it.

But in 1945, the Indonesians were still looking for a way to pressure the Dutch. Many of them were now working at the docks in places like Sydney and Brisbane. There, they spoke to their Australian counterparts, many of them members of one of the militant unions. They advised a boycott of all Dutch ships. Nothing in, nothing out. And especially not military equipment, soldiers, munition, or anything else that could be used to fight the Indonesians. The boycott started at the end of 1945 and by 1946, it really started to bite. So much so, that a high-level meeting was organised between the unions and the Dutch and Australian governments. Lord Mountbatten, then the Supreme Allied Commander for South-East Asia, even flew in for it. The Dutch head negotiator, baron van Van Aerssen, demanded that the unions stop their actions. They laughed at him. ‘You’re not in charge here, friend’, they said. ‘We are’.

The longer the boycott lasted, the more people signed up for it. And it was supported by unions in America, Canada, New Zealand and the UK. It also spread in Australia. To more towns and more trades. Painters, clerks, greengrocers that supplied ships; nobody wanted to touch the Dutch vessels. A large role in keeping the boycott intact was played by Chinese and Indian sailors. A lot of them had been working in Australia during the war. Their countrymen at the docks had been supported the American fleet in Brisbane and even now, they were crewing ships everywhere. During the war, they had not been treated well in White Australia Policy Australia. That had led to protests and the strengthening of their own unions, who were now more powerful than ever. And they had to be because on behalf of his Dutch friends, Prime Minister Curtin presented them with an ultimatum: either you work for the Dutch, or we will deport you. Deporting Chinese and Indians in 1946 meant almost certain death. China and India were in the throes of civil and anti-colonial wars and returning there was not a good idea.

That they were willing to fight for their Indonesian friends regardless, partly had to do with those similarities. The longing for freedom was felt throughout the region and the Chinese and Indians simply understood what the Indonesians wanted and were going through. But there was something else. In 1938, a dispute had played out between the people of the Waterside Workers Federation and the employers in charge of the Port Kembla docks, close to Sydney. In December of 1937, the so-called Rape of Nanking had taken place, an atrocity by the Japanese, when more than a quarter of a million Chinese had been raped and killed in six weeks. The Australians had been appalled and the unions, under the leadership of communist Ted Roach, had decided to boycott Japanese ships. ‘No scrap for the Jap’ was the slogan, and especially pig iron was the union’s bone of contention. The Japanese used pig iron to make weapons to turn against yet more Chinese, and Roach wasn’t having it.

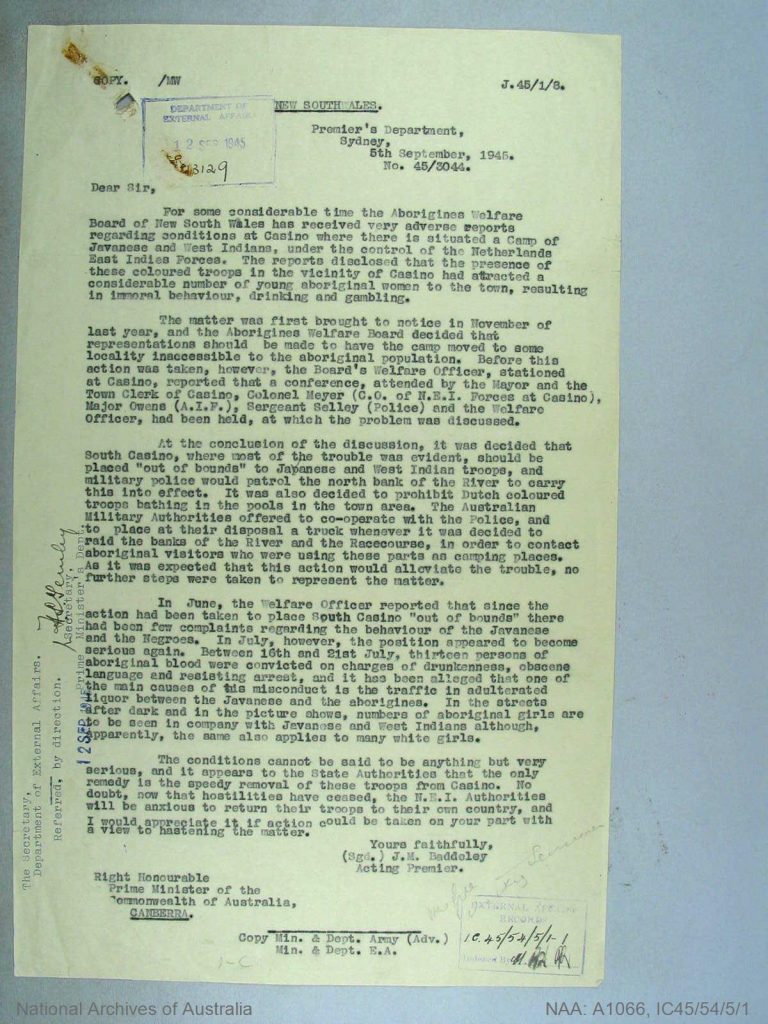

The boycott lasted for ten weeks. Union members were starved, thrown out of their houses and fired. But they kept at it, partly because they were supported by the Chinese who were living in Australia. They sent them money, food and transport if they needed it. The Waterside Workers Federation and the Chinese had forged a bond and that, now, came to fruition in the boycott of the Dutch ships. But they paid a heavy price for that. Hundreds of Chinese and Indians were deported. That, of course, didn’t help the Dutch, who still needed people to crew their ships. From 1946, they started flying them in, mostly from India. Those new people had no idea about either the conflict or the boycott. Often, that was rectified by their countrymen in the unions. When a Dutch ship left with one of those new crews on board, they went after it with dinghies, letting the crew know, in their own language, what was going on. Most of the time, vessels then turned around. Sometimes, crews were forced by the Dutch to come on board, gun against the temple. They then did but jumped ship just before it was about to depart. The boycott lasted until 1949, when Indonesia got its longed-for independence. Most of the Chinese and Indians were then deported or fired. Often, their paperwork was stamped ‘deserter’, which meant that nobody wanted to employ them, ever. Most of them died in poverty.With so many men confined in the Camp, and with the war over with very little for these men to do discipline obviously was difficult to maintain. The town folk started to complain especially about the fact that Aboriginal and also white women were attracted to the camp offering their services to the men. Alcohol was often uses as payments and this led to nuisance in town. The following letter talks about these issues.

This document and file below were researched by Ruby Todorovski, researcher at the University of Queensland.

Repatriation of Indonesians from Casino –1946-48.

In September 1946, 552 Indonesians were still detained at Camp Casino. The Australian Government ordered the Dutch to move these prisoners as the camp was set to close. Of them 223 were due for release on 18th October, 1946. But other 329 release dates range from January 1947 to October 1949. The Australian Government classified these prisoners as political prisoners and asked the Dutch to release them. The Dutch were not cooperative and some of the related issues went on until 1948. This added to the already deteriorating diplomatic relations between the Netherlands and Australia.

See also:

Dutch Camp Casino WWII – Archive Jan de Wit

Javanese from New Caledonia, brought to Casino by the Dutch in 1944.

When the Indonesian revolution came to an Australian country town

The Dutch in charge of Casino – Eighty years of Dutch-Australian diplomatic relations