Propaganda and intelligence gathering.

As the Allied Forces were able to push back the Japanese, by 1943, preparations started in Australia to liberate the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). The Netherlands East Indies Government-in-Exile was established in Camp Columbia, Brisbane to coordinate the liberation and reoccupation efforts from here..

In 1943, intelligence sources had started to show that the economic situation in the Netherlands East Indies had deteriorated to such an extent that the Japanese were forced to take very rigorous and unpopular measures, including forced labor and compulsory supply of raw materials. The periods of hard labor in the rice fields alternating with times of waiting for the harvest without other paid work to be done. Most food was shipped to Japan to feed the troops. In the NEI food shortage became increasingly acute and led to wide spread famine. According to a UN report- published after the war – four million people died in Indonesia as a result of the Japanese occupation.

According to the Dutch these terrible conditions made the population ripe for propaganda. The Dutch argued that successful propaganda in the NEI would be of great military value. This could arouse passive resistance from the population, and this non-cooperative attitude could undeniably have an effect on the Japanese economy and, therefore, also on Japanese warfare.

Furthermore, it could be of value for the secret missions, which were mainly focused on Java, and it could even be the start of a secret intelligence organisation that would be needed when operations against the occupying forces would begin in the future.

Propaganda of the Allies in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was limited compared to, for example, the Allied propaganda actions in Germany in 1943. In the SWAE there had been Allied propaganda pamphlets dropped before elsewhere in the area, but this had been on an ad hoc basis, without too much attention to strategy. The Dutch argued that a new campaign of dropping leaflets would have to be well-coordinated with planned and well-initiated operations if the residents wanted to take this seriously in occupied territory.

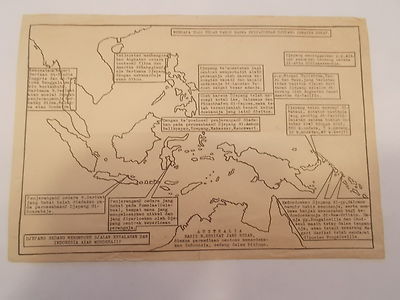

The Dutch also felt that it was time to pay special attention to the island of Java, which was partly within range of the American B-24 Liberator, a four-engine heavy bomber, and of the PBY Catalina of the RAAF and the USAAF. Until now, only East Java had been the occasional target of Allied propaganda. Other important parts of the Dutch East Indies for propaganda were Borneo (Balikpapan and Tarakan), North and South Celebes, Ambon, and West New Guinea.

After various discussions, the Allied headquarters agreed to cooperate in this propaganda task, since the preparation was actually in the political sphere.

The Propaganda Pamphlets

The production of pamphlets, the distribution, and the evaluation of the operations were in the hands of the Far East Liaison Office (FELO), an organisation that was part of the headquarters of the Allied Land Forces (HQ) and was responsible for psychological warfare in the Pacific, especially in the SWPA, the area for which General MacArthur was responsible. The head of this organisation was an Australian, Captain Lt J.D. Bates. One employee was the Dutch Captain P.H. Kramer, who was responsible for psychological warfare in the NW Area. He also received cooperation from Indonesian soldiers who had escaped from New Guinea.

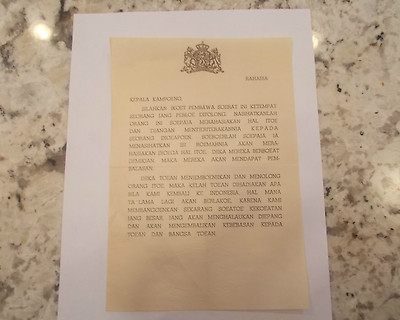

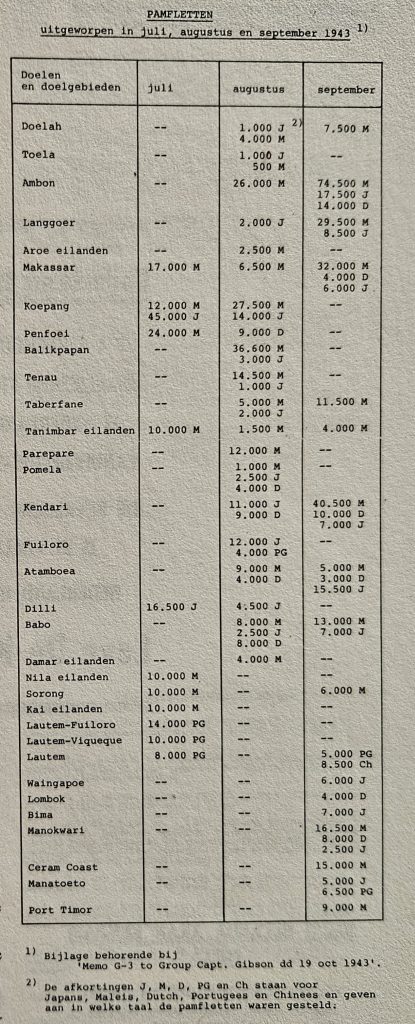

The entire achievement was an all-out effort by the Allied air forces operating in the NWPA and was agreed upon in October 1943. The pamphlets prepared by FELO were in Malay, Dutch, Chinese, Portuguese, or Japanese languages, depending on the operational target area; they were often also bilingual or multilingual. The main sectors eligible for these actions are: Lautem, Halong (Ambon), Nila, Kendari, Amalaia, Laha, Toeal, Aroe, Seroea, Dilly, Japen, Kaimana, Waingapoe, Ambon, Halmaheira, Teoen, Sorong, Balikpapan, Flores, and Makassar.

Here are some topics that were distributed in a pamphlet:

In the Malay, Dutch, Chinese, or Portuguese language:

- Warnings to the Indonesian population to leave the area of military objectives and target areas.

- Ridiculing the Great Asiatic co-prosperity sphere.

- The future fate of Japan.

- Illustrated war news.

- News bulletins.

- Allied advances in the Pacific and the NWPA in particular.

- Superiority of the Allies over the Japanese forces.

In Japanese language:

- Emphasising fear of the truth.

- Show first-line news in images.

- Emphasise Japan’s dependence on the southern part of Asia.

- Map of New Guinea with Allied advances.

- Pacific News Bulletin.

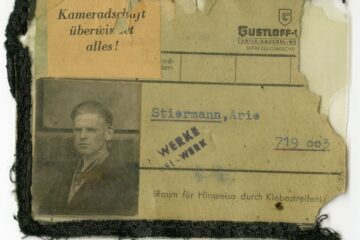

The pamphlets shown below are promoted for sale on the website Worthpoint

Other Pamphlets published in: De Militaire Luchtvaart van het KNIL in de jaren 1942-1945

The allocation of planes and their reconfiguration

Next was the allocation of planes which needed to be reconfigured for the propaganda flights.

The Incredible Reconfiguration of the Planes

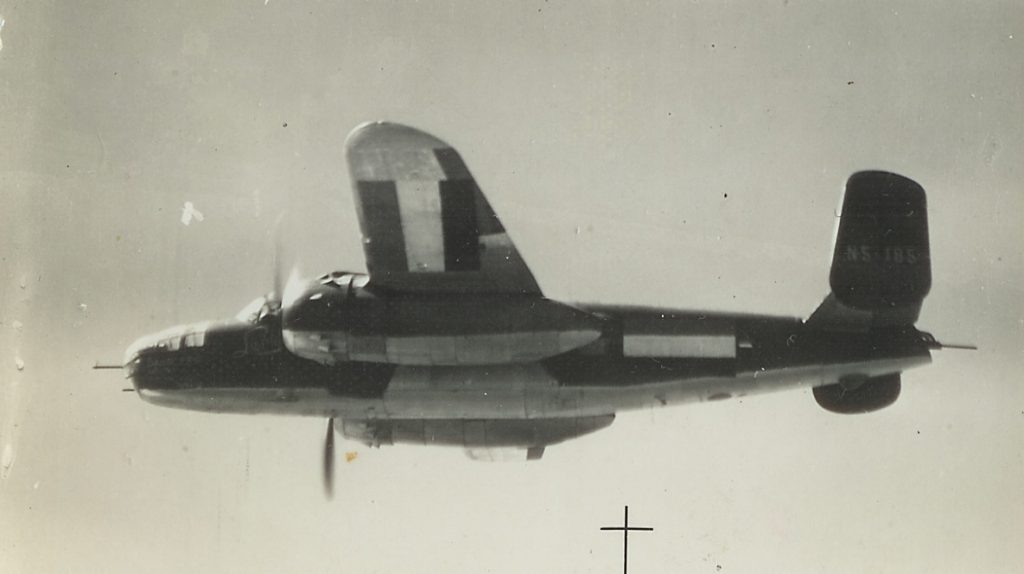

On August 4, 1944, two B-25s were made available: the N5-180 and the N5-185. The -180 was in excellent condition, unlike the -185, which still needed a completely new nose section and was therefore not ready until August 20. To achieve the most economical flying weight, the armament was removed from the aircraft, except for the nose and tail machine guns, while a special metal plate was made to close the turret opening.

A wooden frame of Oregon pine was built into the tail compartment on which a 184-gallon tank could be placed. In addition, 90 gallons of fuel were carried in 4-gallon cans: a total of 23 cans per aircraft, all of which were stowed in the crawl-way between the front and rear compartments. This solved the center of gravity problem quite well. During the flight, the extra tank would first be flown empty, after which the contents of the cans would be poured into this extra tank with a funnel. The location of the cans was precisely measured; after use, the empty cans would be thrown out through the photo hatch. Furthermore, two tanks were taken into the bomb bay, the outermost of which could be dropped during flight.

The fuel system was modified in such a way that the contents of each tank could be pumped separately into the main wing tanks in any desired order. To reduce weight, the VHF and Command sets were also removed from the aircraft. The liaison set, the 1FF, and the interphone for use in the aircraft remained available for communication purposes. Tar, oil, and dust often stuck to the underside of the flying machines, which adversely affected the flying speed. It was now important to have the machines spotless, and to achieve this, special paint remover according to American specifications was ordered. On the fuselage and under the wings, the red-white-blue was painted in extra-large stripes to attract special attention when flying low over the prisons and internment camps.

The Flights to Java

The first two flights in the special planes took place in September 1944 from the Potshot airfield on the western shore of Exmouth Gulf. in Western Australia. (Not sure if these dates line up with the schedule to the left).

The planes had to fly 30 meters above the ocean to avoid radar detection, and when dropping the pamphlets, they had to fly no higher than 100 meters to ensure the pamphlets were dropped within reach of the people at those spots. This was particularly relevant for the dropping above the camps where thousands of civilians were imprisoned by the Japanese.

One plane flew low over Batavia, focusing on the camps and central places. In all, they flew just over one and a half hours over Java. Their total flight took 13 ½ hours.

The main destination of the 2nd plane was the 2nd largest city, Bandung. They were attacked by Japanese Zeros but were still able to drop their pamphlets. Their total flight time was 12 ½ hours.

The total distance covered was approximately 2250 miles (3600 km).

The planes had also been able to shoot at Japanese planes and buildings. A large number of detailed photographs were taken, which were critical for the intelligence services as well as for the planning aid once the area was liberated.

The second flights took place in January 1945, in the N5-185. Departing from Broome, this time the trip would take in Surabaya, Solo, Semarang, and Ambar Awang (targeting a massive camp with women and children). They flew for over 4 hours over Java. After 14 ¼ hours, they glided back into Broome using the last few drops of fuel.

The same crew in the same plane made another trip two days later, this time the main focus was to take extensive photographs of the port Tjilatjap on the southern coast of Java.

The people in the camps will most certainly have enjoyed the arrival of the planes, especially when they flew so low over the camps with the clearly visible Dutch flag painted on the plane. It most certainly provided them with hope.

The following information is from the diary of Guus Hagers the pilot of the N5-185. The pictures below that entry are from his plane ‘Lienke’ – the name of his young wife he had to leave behind in Java and who ended up in one the notorious Japanese camps. All three images with thanks to Guus van Oorschot in the Netherlands.

The effect of the pamphlets on the Indonesian people will have been mixed, as there was already a clear move towards independence. The last thing they wanted was a return of the Dutch to their land. See also: The end of the war.

Source: De Militaire Luchtvaart van het KNIL in de jaren 1942-1945