By Tony Thomas

Of all the accounts of the earliest Dutch arrivals in Australia, the wreck of the Concordia seems the strangest. A “great vessel” of 900 tonnes with 130 on board, it departed Java bound for the Netherlands in 1708. After a storm south of the Sunda Strait, the Concordia disappeared.

Substantial but not conclusive evidence exists that 80 men and 10 women survivors wound up on Australia’s north or west coast, with good supplies from the ship. They were said to have trekked east 2000km, following watercourses of that era to about present-day Hermannsburg near Palm Springs in central Australia. They settled by a river and after half a dozen generations and interbreeding with Aborigines, they multiplied in 125 years to 300 colonists.

They were discovered in May 1832 by a British army exploring expedition, whose leader “Lt Nixon”, a pseudonym, left a detailed account of eight days’ stay with them. Lt Nixon could understand them as he had been schooled in Holland. His report said,

“Their traditional history is, that their fathers were compelled by famine, after the loss of their great vessel, to travel towards the rising sun, carrying with them as much of the stores as they could during which many died; and by the wise advice of their ten sisters [women?] they crossed a ridge of land, and meeting with a rivulet on the other side, followed its course and were led to the spot they now inhabit, where they have continued ever since. They have no animals of the domestic kind, either cows, sheep, pigs or anything else: Their plantations consist only of maize and yams, and these with fresh and dried fish constitute their principal food which is changed occasionally for Kangaroo and other game; but it appears that they frequently experience a scarcity and shortage of provisions, most probably owing to ignorance and mismanagement; and had little or nothing to offer us now except skins. They are nominal Christians: their marriages are performed without any ceremony: and all the elders sit in council to manage their affairs; all the young, from ten up to a certain age are considered a standing militia, and are armed with long pikes; they have no books or paper, nor any schools; they retain a certain observance of the sabbath by refraining from their daily labours, and perform a short superstitious ceremony on that day all together; and they may be considered almost a new race of beings.“

The 1300-word account was published in January 1834 in the respectable Leeds Mercury newspaper. A retired Indian Army Lieutenant, Thomas Maslen of Halifax, submitted it after somehow accessing Nixon’s official report. Maslen altered and disguised some details.

More than 30 years later explorers and missionaries passed through central Australia, but all physical traces of the Dutch community had disappeared.

Australia’s academic historians have shown no interest in this story, clearly regarding it as not worth their time to refute. If true, of course, the story would require a significant re-writing of European settlement of Australia from the First Fleet in 1788.

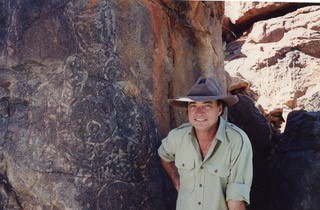

The narrative would remain nothing but travellers’ tales, except for Australia’s well-known Bush Tucker Man, Major Les Hiddins AM, now 77 and retired in Townsville. In the 1990s he produced with the ABC several series on Australia’s far-outback history and botany, centred around how to survive from water and plant foods. Episode 5, Series 3 (still on YouTube) covered his earliest attempts to verify or refute the “Dutch colonists” story. Through detailed archival research in Australia, London and Netherlands, he has fleshed out many key issues. After interviewing Hiddins, I published his theory here, with embedded links to the key document.

Hiddins says one fact gives the Leeds Mercury account high credibility. The Leeds report names the 1832 Dutch leader as “Van Baerle”, a rare Dutch surname. Hiddins’ Dutch archivists have located on the Concordia an officer named Constantijn Van Baerle. If the 1834 story were fictitious, the name Van Baerle from the ship in 1708, and the Dutch colony leader’s name Van Baerle in 1832, would be inexplicable.

The second key fact is that in 1851, the Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië [Magazine for the Netherlands East Indies] carried a report by the Dutch harbour master at Semarang, Java, Lt Van Bloomestein. He said that a passing British ship’s captain had told him two decades earlier that he carried passengers who had discovered the 300 Hollanders “living in a totally primitive manner”. Van Bloomestein had passed on the details to Indies Governor-General De Eerens but had heard of no follow-up. There was no reason for the harbour master, long after the event, to fabricate such a story.

Hiddins believes, based on textual clues, that the secret army expedition was ordered by Swan River’s first Governor James Stirling and run by his subordinate and explorer Lt Robert Dale.

Advances in DNA analysis can determine whether Indigenous Australians in central Australia have inheritances from Dutch ancestors in the 18th century. Melbourne University DNA expert Professor Neil McGregor has examined DNA from two Indigenous Australians and reviewed further DNA from a third-party study. He says the groups’ DNA is consistent with matches from Dutch and Belgian citizens, but not necessarily from the 18th-19th centuries. McGregor, who is Clinical Associate Professor in the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, says that until someone can obtain for him 20-30 further relevant DNA samples, he can draw no conclusions. “My findings do not rule out the story, which is a very interesting one,” he says.

Many mysteries remain – including European-style cave art and graffiti noticed by Central Australia’s first explorers, and Aboriginal women with Old-Testament names met by the first missionaries. But Les Hiddins feels he has reached his limit after 20-30 years of investigation and documentation. It’s a pity that professional historians are unwilling to tackle the affair.

This is a shortened version of Tony Thomas’ article “Were there Dutch Castaways in Central Australia?” published in Quadrant on 9 March 2023: https://quadrant.org.au/opinion/history/2023/03/were-there-dutch-castaways-in-central-australia/

Contact: Tony Thomas tthomas061@gmail.com