From warship to Luna Park: the remarkable afterlife of Dutch submarine K-XII

The wartime story of the Dutch submarine HNLMS K-XII is reasonably well known among naval historians, but its Australian afterlife is one of the most unusual episodes in Dutch–Australian maritime history. Few Allied submarines ended their days as a tourist attraction at Luna Park or as a playground for children on the shores of Manly. Yet this is precisely how K-XII spent the final years of its existence.

From Java to Fremantle

Launched in Rotterdam in 1924 and commissioned the following year, K-XII belonged to the Dutch colonial submarine force designed for operations in the Netherlands East Indies. After a twelve-week voyage from Europe, the submarine joined the Dutch fleet at Surabaya.

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, K-XII came under British operational control and was soon involved in combat operations. In the first weeks of the war it successfully attacked Japanese shipping, sinking the freighter Toru Maru and the tanker Taizan Maru. On Christmas Day 1941, K-XII also rescued the crew of a downed British Catalina flying boat, an episode remembered in several wartime accounts.

As Japanese forces advanced rapidly toward Java in early 1942, K-XII escaped to Australia, arriving in Fremantle on 20 March. From there it undertook patrols in support of the Netherlands East Indies intelligence service (NEFIS), including covert operations to land agents along the Javanese coast. By mid-1943, however, the ageing submarine was no longer fit for frontline service.

K-XII was therefore assigned to the Admiralty’s Anti-Submarine Division for ASDIC training duties. These exercises, involving repeated sonar tracking by Allied ships and aircraft, placed further strain on the vessel’s already worn structure and systems.

Decommissioning and an unexpected new role

On 22 March 1944, K-XII sailed from Fremantle to Sydney to await decommissioning. In September 1944, the submarine was formally struck from the Royal Netherlands Navy list.

Rather than being scrapped immediately, K-XII entered an unexpected and colourful new phase. A group of Australian businessmen purchased the submarine, recognising its novelty value in the immediate post-war years. From late 1945, K-XII was moored beside Luna Park in Sydney, where visitors paid a small fee to climb aboard, peer through the periscope and explore the engine room.

Sydney was experiencing electricity shortages at the time, and one of K-XII’s remaining engines, together with its generator, was used to help power lighting at Luna Park. Dutch naval machinery thus helped keep an Australian amusement park running at night—an improbable but well-documented footnote in post-war history.

In 1946, the submarine was relocated across the harbour and moored beside the Manly harbour pool. Contemporary newspaper accounts describe a specially constructed jetty that allowed residents and tourists to walk directly out to the submarine, turning it into one of Manly’s most unusual attractions.

Shipwreck at Fairlight

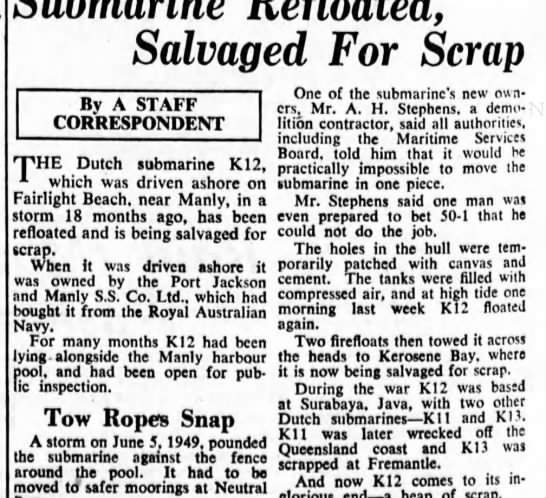

Manly Cove was exposed to heavy southerly weather, and K-XII repeatedly collided with its moorings. In early June 1949, during a severe storm, the owners attempted to move the submarine to a safer anchorage. The towline snapped, and K-XII drifted ashore onto the rocks at Fairlight, where it became firmly wedged.

Salvage attempts failed. At one stage, even a salvage barge was washed onto the rocks. While authorities regarded the stranded submarine as a nuisance, local children saw it as something quite different: a genuine wartime submarine to climb over and explore.

A long and slow farewell

In early 1950, a new syndicate purchased the stranded vessel, hoping to refloat and scrap it profitably. Work began by stripping the submarine of weight. Batteries, motors, floor plates and internal fittings were hauled ashore using rigging strung from the deck gun to the shoreline.

After eighteen months of effort, K-XII was finally refloated in January 1951 and towed to Balls Head Bay to begin demolition. The process proved slow and repeatedly disrupted. On one occasion, vandals removed hull plugs while the submarine was beached in the Parramatta River, causing it to sink again and delaying work for months.

Using underwater cutting gear and explosives, the hull was gradually dismantled. The final remnants were not removed until 1961—more than a decade after salvage operations began. Much of the recovered metal was ultimately sold as scrap to Japan, a final irony for a submarine that had once fought Japanese shipping.

A Dutch–Australian story worth remembering

The life of HNLMS K-XII spans colonial service in the Netherlands East Indies, combat and intelligence operations during the Pacific War, and an extraordinary post-war existence in Sydney. From wartime patrols and NEFIS missions to Luna Park attraction, shipwreck and slow demolition, its Australian afterlife is unmatched among Allied submarines.

Thanks to contemporary newspaper reporting and later historical work—most notably John Morcombe’s article in the Manly Daily (28 July 2016)—the remarkable story of K-XII remains part of Sydney’s maritime memory and a distinctive chapter in Dutch–Australian wartime history.

See also: Dutch Submarines operating from Australia during WWII