The ‘Fatima’ was bound from Melbourne to Batavia (Jakarta). On the 26th of June 1854 the vessel was wrecked on the Great Detached Reef, twelve miles south of Raine’s Island. The shipwrecked crew and passenger were recovered by the Dutch ship ‘Bato’ and arrived in Batavia on the 25th of July 1854. No lives were lost.

On the 6th of July they picked up the survivor of the Barque ‘Thomasine’. This ship was wrecked on the Reef, one seaman was lost and the eighteen survivors which included the captain, his wife and three children, spent fourteen days in open boats before being picked up by the Dutch vessel Bato off Bird Island in Torres Strait after a voyage of 700 miles.

A day later on July 7 the Bato rescued survivors of the barque ‘Elizabeth’. On a voyage from Melbourne, Victoria to Moulmein, Burma, she ran aground on a reef in the Torres Straits. She was refloated but was consequently abandoned off the Great Barrier Reef. Her crew reached Booby Island, New South Wales on 3 July, where they were rescued 4 days later.

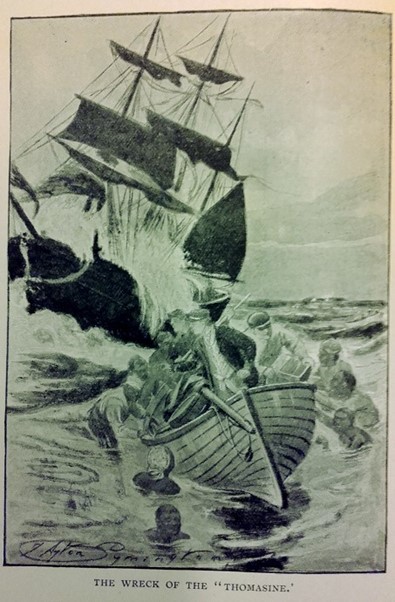

The wrecking of the Thomasine

his story takes place in 1853 when Captain Holmes was owner and Captain of the barque “Thomasine”. After being chartered by the Spanish Government to take a cargo to Port Isabella in the Philippines and suffering mutiny and desertion of the crew, Holmes secured a new crew and a cargo of tea in Hong Kong and sailed to Sydney. It being the time of the gold rushes there was no difficulty in finding men willing to sail to Australia. Holmes had his wife and three children aboard including youngest daughter Thomasine, born on the voyage. Armed with a brand-new Admiralty Chart and a new crew composed of Malays, Manilla men, and one Bengali, Holmes set sail, intending to pass through Torres Straits and return to China in search of a new cargo.

Sadly, Holmes’ new Admiralty Chart proved less than complete in the marking of dangerous reefs off the coast of Queensland and somewhere outside the Great Barrier Reef close to where Cairns is now situated the ship ran into difficulties.

I looked at my watch and told the second officer to strike eight bells. No danger was then in sight, but the man had hardly finished when the ship struck heavily three or four times. Nothing was to be seen in the way of breakwaters. I took it to be a mushroom reef, and, fearing there might be something ahead, I altered the ship’s course to the westward, at the same time directing a good look-out to be kept. I went to my cabin to look at the Chart but was quickly called back on deck by the cry of “Breakers Ahead.” I found that right ahead and also both right and left, there stretched a long line of white rolling breakers, upon which, to my horror, I found we were approaching very close.

The Captain found the ship surrounded by reefs. I made every effort, but, to my mortification, whichever way we went, the terrible reef confronted us, compelling me to “go about” every quarter of an hour. This trying operation had to be repeated from eight o’clock until daylight next morning, for only by the strictest vigilance could we hope to escape being dashed upon the reefs. Indeed, had this been our fortune, the night being dark, all might have perished. By the efforts of Captain and crew the ship was kept off the reefs till dawn revealed the extent of their danger. I was now surrounded by two immense reefs, separated by one or two miles, thus forming a gulf ten or twelve miles deep. These were united at the Northern end by a thin ridge of coral with narrow openings from which I was about three miles distant. I was thus in a trap, with danger on all sides, and, to all appearance, with no hope of escape. And yet the scene before me at daybreak was grand. The deep blue water, the long range of white rolling breakers, and the blue sky above presented a scene unspeakably grand and impressive, though under the circumstances terribly dispiriting.

With the wind increasing and no apparent means of escape from their predicament the Captain determined to attempt to run through an opening in the ridge connecting the two reefs, but unfortunately the opening was only superficial and the ship struck heavily, and with an awful crash. The Captain saw to the launching of the ship’s two boats with considerable difficulty and the loading of a bag of biscuits, a beaker of water, a small quantity of preserved mutton and a compass.

Captain Holmes divided the crew and supplies between the two boats and headed north in an attempt to reach Booby Island in Torres Strait where there were supplies kept for shipwrecked sailors. It was the 20th of June when the ship went down and by 6 July, they had reached Bird Island off Cape York where they met up with the Dutch ship “Bato”. They had a difficult journey with limited food and water, little shelter and inadequate clothing and with the Captain’s wife and three young children on the boat. The two boats were often separated but each time they managed to find each other and were all taken on board the Dutch ship and delivered safe to Batavia. Source: Life and adventures on the ocean : a personal narrative published in around 1902, courtesy of the State Library of Queensland.

After this disaster the reefs on which he wrecked his ship was named after the captain and is now known as Holmes Reef.

See also:

The wrecking of the Dutch ships Hester en Doelwyck on the Reef – 1854