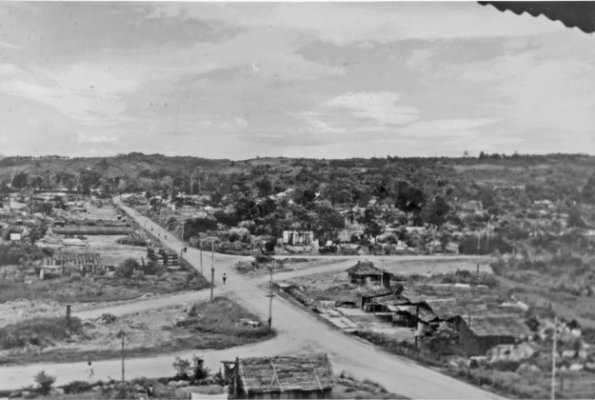

The Japanese advance through Southeast Asia in early 1942 brought the Allies to the brink of disaster. Ambon, a strategic island in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI), was garrisoned by Dutch and Australian troops under the Gull Force detachment. When Japan invaded in late January 1942, the Allied defence quickly turned into a desperate struggle for survival.

Source: Netherlands Indies Government Information Service (NIGIS)

A doomed defence

The Ambon garrison included approximately 1,100 Australian soldiers from Gull Force and several hundred KNIL (Royal Netherlands East Indies Army) troops under the overall command of Lieutenant-Colonel C. L. van Straten. They faced overwhelming Japanese landings supported by naval and air superiority.

There was a short Battle of Ambon but despite determined resistance, Japanese forces captured key positions quickly. Air attacks destroyed fuel and communications facilities, and by early February, organised defence had broken down. Many soldiers were captured, while others retreated into the jungle or sought escape by sea.

Flight under fire

The escapes from Ambon were improvised and dangerous. A handful of Dutch and Australian personnel managed to flee by small boats, often with the assistance of local Indonesian sailors.

Some of the named individuals involved in the escape included:

- Lieutenant J. Brunsting of the KNIL, who organised the movement of a small group of soldiers to Ceram by native craft.

- Lieutenant-Commander A. van Miert of the Royal Netherlands Navy, who coordinated one of the boat escapes under the constant threat of Japanese patrols.

- Lieutenant H. Gilles and Lieutenant Kruyswyk, both of the KNIL, who assisted in evacuating men from the southern part of the island.

- Dutch Consul Craandijk, a key civilian figure, who eventually escaped the island and later assisted with Dutch refugee coordination in Australia.

- Sergeant Tahija, an Indo-Dutch soldier, who showed exceptional skill in navigating local waters and liaising with Indonesian boatmen.

Some groups made their way to Ceram and then onward to Timor or Australia, while others attempted to cross directly to northern Australia in tiny vessels. Navigation was primitive, relying on the stars and local knowledge, and food and water were scarce. Several escapees perished at sea or were captured and executed when intercepted by Japanese patrols.

Acts of heroism

The escape from Ambon highlighted remarkable acts of courage and improvisation. Dutch naval personnel and Indonesian boatmen risked their lives ferrying soldiers between islands. Officers such as Brunsting and van Miert maintained discipline and morale under extreme conditions.

Australian soldiers also displayed heroism in their attempts to evade capture, often relying on Dutch knowledge of the islands and the support of local Indonesians. Some of the men who escaped later made their way to Australia and joined the Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS) or supported Korps Insulinde in guerrilla operations across the NEI.

Strategic and human legacy

The fall of Ambon and the desperate escapes that followed illustrate the strategic fragility of the Allied position in early 1942. The garrison had been under-equipped and isolated, reflecting the broader problem of Dutch and Australian preparedness.

Yet the heroism of the escapees, and the sacrifice of those who did not survive, formed a shared wartime memory that strengthened Dutch–Australian bonds. Their stories demonstrate both the dangers of the early Pacific War and the resilience of small Allied units fighting against overwhelming odds.