A little-known episode of Dutch–Australian post-war cooperation

Introduction

In the chaotic months after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, the Netherlands East Indies entered a turbulent and violent transition. The return of Dutch administrative and military forces coincided with the rise of the Indonesian independence movement and a widespread collapse of security, especially on Java. Within this unsettled landscape, Allied teams were deployed to locate prisoners of war, gather evidence of Japanese war crimes, and prepare material for the upcoming trials. Among those teams were Australian investigators working alongside Dutch, British and American personnel.

On 17 April 1946, three Australian officers – Flight-Lieutenant H. M. MacDonald, Squadron Leader F. G. Birchall, and Captain Alastair MacKenzie – were murdered roughly 35 kilometres south of Batavia Jakarta), near Buitenzorg (Bogor), while travelling on official duties related to war crimes investigations. The incident received international attention but has largely faded from public memory. Yet it is an important example of how Dutch and Australian interests intersected in the immediate aftermath of the war.

Dutch and Australian cooperation after the Japanese surrender

Although Dutch civil authority had not yet been fully restored across Java, the Netherlands East Indies government-in-exile had returned from Brisbane, Australia in late 1945 and was re-establishing its institutions in Batavia. At the same time, the Allied South East Asia Command (SEAC) retained overall responsibility for security and for the evacuation of prisoners of war and internees. Australia played an active role in these efforts, driven by the large number of Australian POWs held in camps across Java, Sumatra, Ambon and Borneo.

From mid-1945 Australian forces were also used as occupation troops in parts of the Netherlands East Indies. Australian brigades accepted Japanese surrenders and maintained order in areas such as Borneo and the Celebes, and remained in some of these regions into early 1946, until the Netherlands could rebuild and deploy its own military forces and administration. In practice this meant that, in several former Dutch territories, Australians temporarily stood in for Dutch troops in the first post-surrender months.

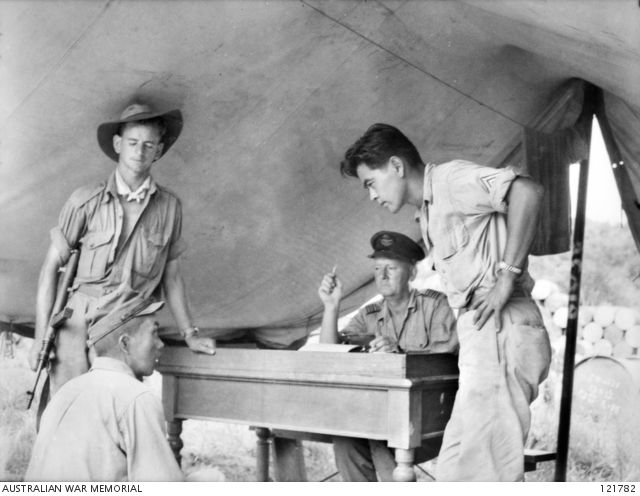

Australian war crimes personnel were attached to SEAC and operated under an Allied mandate that required close cooperation with Dutch authorities. Much of the evidence they were seeking concerned atrocities committed by Japanese forces against Dutch civilians and KNIL personnel, as well as Indo-European and Indonesian camp inmates. The investigations therefore served both Australian and Dutch interests.

Indonesian perceptions and a climate of insecurity

For Indonesian nationalists, the sudden appearance of British and Australian uniformed troops across the archipelago was deeply political. After the Japanese surrender, the Dutch sought to reclaim the Netherlands East Indies, while Indonesian leaders saw the end of the war as their opportunity for independence. In this context, many Indonesians perceived Allied troops as supporting the restoration of Dutch colonial rule, and hence as opponents of the new Republic.

The result was a confusing and dangerous situation on Java in late 1945 and early 1946. Dutch and Allied authorities attempted to re-establish order, while Republican forces and local militias contested their presence. Attacks on Dutch officials, Indo-European civilians and Allied patrols were common in parts of West Java. It was into this volatile environment that the Australian war crimes investigators were sent.

The journey to Bogor

The three Australian officers were travelling south from Batavia on 17 April 1946 on their way to gather testimony from former prisoners and local witnesses. The region around Bogor was still highly volatile. Dutch troops were stationed in the main towns, but republican control, local militias and unresolved tensions made the areas outside the towns dangerous for Allied personnel.

Contemporary Dutch and Australian reports indicate that the officers were ambushed on the road between Batavia and Bogor. Their vehicle was stopped, and the men were killed at close range. The identities of the attackers were not definitively established, though the incident occurred during a wider pattern of armed attacks directed at Allied and Dutch personnel during the early phase of the Indonesian Revolution. Australian press reports at the time simply referred to “three Australian war crime investigation officers 35 miles from Batavia” murdered by Indonesian attackers.

The Australian were buried with ceremonial honour provided by the British RAF at the Commonwealth Menteng Pulo Cemetery in Jakarta.

A short film of the funeral held in Batavia on 18 April 1946 is preserved by the Imperial War Museum (catalogue no. JFU 579). Titled Funeral of Australian War Crimes Investigators Killed in Java, it shows a flatbed lorry carrying the flower-covered coffins of Flight-Lieutenant McDonald and Captain MacKenzie, accompanied by RAF Regiment pallbearers and the burial ceremony. The footage is not available online but can be accessed or licensed through the IWM’s Image and Film Licensing team.

Australian and Dutch responses

News of the killings was quickly communicated to both Canberra and The Hague. Australian diplomatic cables described the incident as a major setback for the war crimes investigation program. Indonesian Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir conveyed his government’s regret to the Australian mission in Jakarta, explicitly referring to “the murder of the three Australian officers near Bogor”. Dutch authorities expressed regret and emphasised the difficulties of maintaining security in regions where Allied forces were thinly spread and political loyalties were divided.

Within Dutch administration the case became known as part of the “Buitenzorgse Affaire” and was investigated alongside the killing of the local official Toembelaka and other violent incidents in the Buitenzorg (Bogor) area. Dutch archival inventories list extensive correspondence, reports and minutes concerning “de moord op Toembelaka en drie Australische militairen” and the restoration of republican administration in the district.

Although the murders were never fully solved, they highlighted the broader dangers faced by Dutch and Allied personnel in 1945–46. Dutch officials and KNIL units were themselves regular targets of armed groups, and many Indo-European civilians who had survived Japanese camps found the post-surrender period even more perilous. The deaths of the Australian officers therefore fit into a wider pattern of violence affecting Dutch, Indisch, Australian and British individuals during this transitional year.

Conclusion

The killing of three Australian war crimes investigators near Bogor in April 1946 is an important but often overlooked moment in Dutch–Australian wartime and post-war history. It took place within a landscape shaped by Dutch return, Allied responsibility, Indonesian nationalist aspirations and widespread instability. The investigators were in Java to help document atrocities committed against Dutch, Indisch and Australian prisoners—an effort that reflected deep cooperation between the Netherlands and Australia.

Recognising this event helps us appreciate the shared and sometimes tragic experiences that bind Dutch and Australian histories in the Asia–Pacific region. It also honours the memory of the Australians who lost their lives while participating in a difficult and dangerous mission in the service of justice and reconstruction.

Paul Budde – December 2025

Sources and further reading .

– Inventaris van het archief van de Algemene Secretarie van de Nederlands-Indische Regering 1942–1950, entries 3022–3024 on the “Buitenzorgse Affaire” and the murder of Toembelaka and three Australian servicemen.

– Nationaal Archief, archief Procureur-Generaal 2.10.17, inventory entries referring to “moord op de Australische officieren” and the Buitenzorgse Affaire.

– P. J. Drooglever et al., Guide to the archives on relations between the Netherlands and Indonesia 1945–1963, entries on the “Murder of three Australian officers in Java”

– Trove. Australian government cables and contemporary press reports, for example “Murder in Java”, The Mercury, Hobart, 27 April 1946.