During the Second World War, the Japanese occupation of the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) led to the internment of tens of thousands of Dutch civilians. Among them were Catharinus Lawant, his wife Maria, and their daughter Martina. Their story—documented through personal sketches and migration records—offers a window into a wider Dutch wartime and migration experience that continues to resonate within Australia’s multicultural heritage.

Life in the Indies before the war

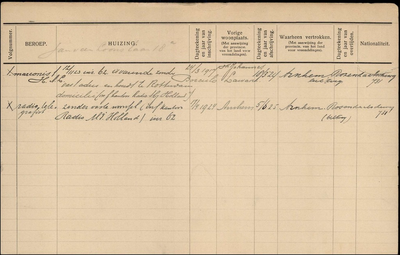

Catharinus Lawant was born in 1896 in Assen, Netherlands. After serving as a wireless operator on Dutch passenger liners following the First World War, he moved to the Netherlands East Indies, where he married Maria van Woerden in 1915. The couple settled in Bandung, West Java, and had two children: Johannes (born 1928) and Martina (born 1929).

Their life in Bandung was part of a broader Dutch presence in the Indies—one characterised by colonial infrastructure, civil service roles, and the economic networks of Dutch expatriates and Indo-Europeans (Indische Nederlanders). But this relatively stable life was disrupted in 1942 when Japan invaded and occupied the islands.

Internment under Japanese occupation

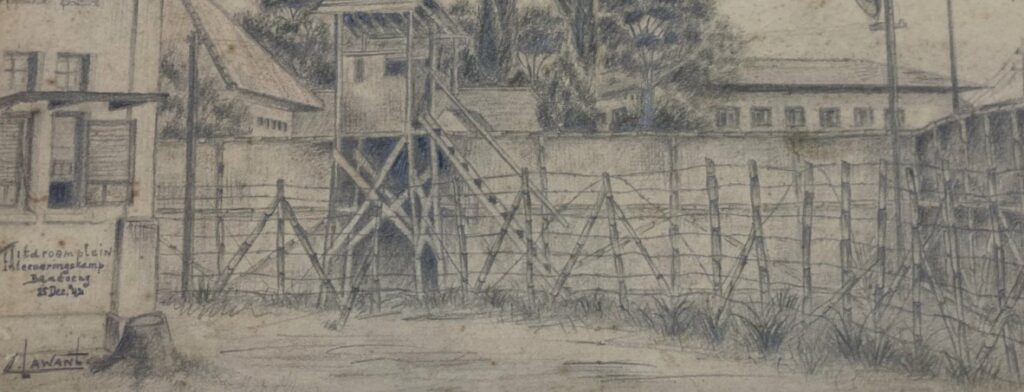

From December 1942 until liberation in 1945, the Lawant family was interned in Japanese camps in and around Bandung. As was common practice, families were separated: men were placed in camps like Tjitaroemplein (Tjitarum square), while women and children were confined elsewhere under strict surveillance and hardship.

Catharinus documented life inside the camps through a series of pencil sketches. One drawing shows the boundary fencing at the Tjitaroemplein camp—barbed wire and bamboo screens defining a world of confinement. Another depicts men performing kitchen duties in October 1943, revealing both the communal nature of camp life and the daily struggle for survival.

According to records from the State Library of Queensland, which now holds the Lawant family papers, the family—like many others—endured severe physical deprivation and psychological strain. Leaflets dropped by Allied aircraft in late August and early September 1945 warned internees to remain in place and assured them that help was coming.

After liberation: trauma, displacement, and return

Following the end of the war, the Lawants were freed, but their ordeal was far from over. Like many former internees, they emerged from captivity traumatised and destitute. Compounding their suffering was the violent struggle for Indonesian independence, which made remaining in the archipelago untenable for many Dutch families.

The Lawants returned to the Netherlands, mourning the loss of friends and family, and navigating the economic and emotional aftermath of their wartime experiences.

Migration to Australia

The family eventually looked to Australia as a place of renewal and stability. In June 1951, their son Johannes emigrated aboard the Sibajak, initially settling in Victoria before relocating to Brisbane. In 1964, he married Johanna Kessler.

In 1960, Catharinus, Maria, their daughter Martina, and her husband Karl Schotz arrived in Brisbane on the Groote Beer under the Netherlands Migration Agreement. The family settled in Moggill, Queensland, where Karl and Martina were naturalised in 1965. Their arrival was part of a broader wave of Dutch postwar migration that brought tens of thousands of new residents to Australia.

The Lawant family’s decision to migrate—like that of many others—was shaped not just by opportunity, but by displacement. Their move to Australia was a continuation of a long journey from colonial privilege, through wartime trauma, to new beginnings in a distant land.

Legacy and remembrance

Today, the Lawant family’s story lives on through sketches, documents, and personal papers held at the State Library of Queensland. These materials offer rare visual testimony to life in Japanese internment camps and provide insight into the broader Dutch-Australian migrant experience.

Their experience is emblematic of many Dutch families who lived through the collapse of empire, endured internment, and went on to rebuild their lives in Australia. Through personal resilience and community contribution, they enriched Australian society with their heritage and history.