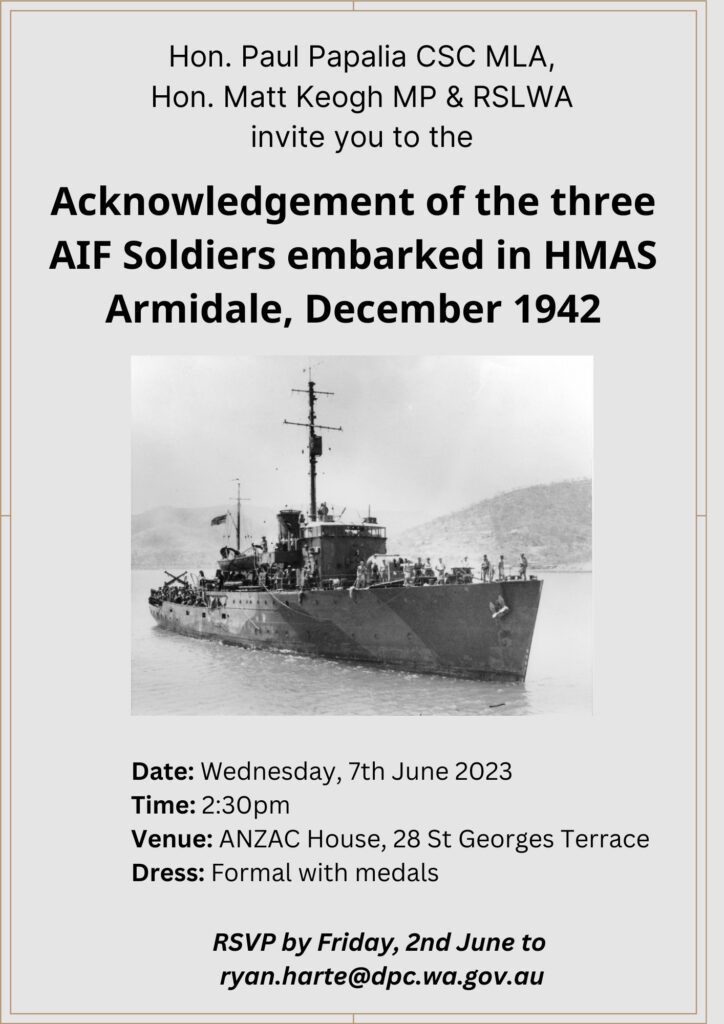

In 1938, amidst escalating tensions of war, the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board recognised the necessity for a versatile ‘local defence vessel’ capable of anti-submarine and mine-warfare duties. This need birthed the concept of the HMAS Armidale, envisioned as a vessel with a displacement of around 500 tons, capable of reaching speeds of at least 10 knots and with a range of 2,000 nautical miles. However, due to circumstances of the war, the design was altered to a 680-ton vessel, equipped with a 4-inch gun, asdic, and the ability to deploy depth charges or minesweeping equipment.

Construction of the Armidale began on September 1, 1941, at Morts Dock & Engineering Co in Sydney, Australia. Launched on January 24, 1942, the ship was commissioned on June 11 of the same year.

Assigned primarily to convoy escort duties along the Australian coast and to New Guinea, the Armidale’s along with its sister ship HMAS Castlemaine and the auxiliary patrol boat HMAS Kuru, the service took a fateful turn in late November 1942 when it was tasked with a critical mission: to bring Dutch soldiers to Timor and to evacuate the 2nd Independent Company and Portuguese refugees from Betano Bay. They would also deliver relief forces. The ship was carrying a crew of 83 plus 3 AIF men (bren gunners) to provide covering fire at the beach for two Dutch officers and 61 Netherlands East Indies troops which was put together in Australia and under command of the 1st lieutenant of the infantry Stoll.

This mission bore significant weight for the Dutch, as their troops were among those being evacuated. The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army, a vital component of the Dutch colonial presence in the region, stood alongside Australian and Portuguese forces, reflecting the multinational effort to combat Japanese aggression.

The operation was fraught with challenges from the start. First it was delayed due to bad weather, next Japanese reconnaissance planes spotted the convoy, prompting concerns of imminent attack. Despite the risks, the mission pressed forward. On November 30, Armidale, Castlemaine and Kuru, ventured towards Betano Bay. Encountering delays and facing multiple air attacks, the corvettes reached their destination in the early hours of December 1. The Kuru had drop 77 Portuguese women and children off at HMAS Castlemaine who evacuated them to Darwin.

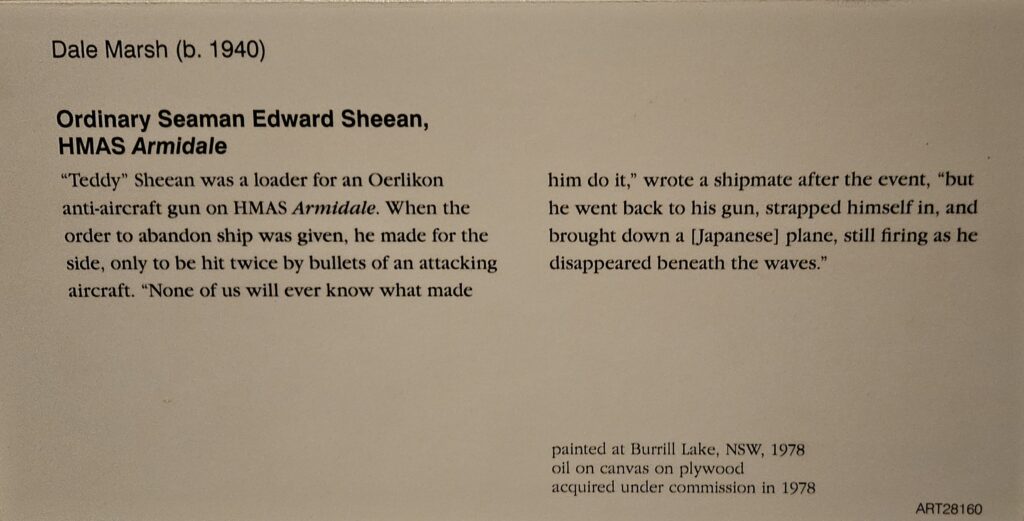

Determined to fulfill their duty, Armidale and Kuru set out to return to Betano Bay, but their efforts were met with tragedy. Attacked by Japanese dive-bombers, the corvette sustained heavy damage. Two torpedoes struck the vessel, plunging it into chaos. As soldiers and sailors evacuated into the water, they became targets of strafing runs by Japanese aircraft.

Amidst the wreckage, survivors clung to debris, their hopes resting on the uncertain promise of rescue.

Amidst the chaos and devastation of the sinking of HMAS Armidale, Lieutenant Commander David Richards, rallied the surviving crew, directing efforts to salvage what they could from the wreckage. As the only unwounded officer with the capacity to navigate, Richards assumed the weighty responsibility of guiding his men to safety.

On December 5th, their perseverance bore fruit when they were rescued by HMAS Kalgoorlie. Seventeen survivors, a mere fraction of the twenty-two who had embarked on their harrowing journey from the sunken corvette, were plucked from the unforgiving waters.

Yet, the trials were far from over. The ship’s whaler, riddled with bullet holes and waterlogged, posed a formidable challenge. With ingenuity and determination, the remaining survivors transformed the damaged vessel into a lifeline. Using whatever materials they could salvage, they patched the bullet holes with shreds of their undergarments and lashed canvas over the hull to staunch the leaks.

Their journey towards Darwin was fraught with hardship. Painfully sunburned and with dwindling supplies, the men battled exhaustion and delirium. Hallucinations blurred reality, and false hopes of sighting the coastline teased their weary minds. Rain provided a brief respite, offering precious drops of water to quench their parched throats.

Their salvation came on December 8th, when a searching Catalina aircraft spotted their makeshift raft. Food and provisions were dropped from above, providing a lifeline to the desperate survivors. Finally, on December 9th, HMAS Kalgoorlie arrived to whisk them to safety, bringing an end to their nine-day odyssey of survival.

Yet, amidst the triumph of rescue, tragedy lingered. Friction among with the Javanese soldiers as well as the Dutch officers, compounded by the perils of the sea, led to separation. The Netherlands East Indies soldiers aboard the raft vanished into oblivion, their fate shrouded in mystery. Despite efforts to locate them, they drifted away.

The sinking of HMAS Armidale was a devastating blow, claiming the lives of 40 personnel from the ship and 60 Royal Netherlands East Indies Army soldiers.

The legacy of HMAS Armidale endures as a testament to the bravery of those who served and sacrificed in the name of duty and honour, transcending national boundaries in a shared struggle against tyranny.

Below the list of missing people.

Additional information, based on the list in the pdf above, provided by Gerard van Haren

Abbreviations: Dutch = English

Kap = kapitein = Captain

inf = infantrie = Infantry

Lt = luitenant = Lieutenant

art = artillerie = Artillery

OvG = Officier van Gezondheid = Army Doctor

Eur = Europees = European

sgt = sergeant = Sergeant

Jav = Javaans = From Java

ekl = eerste klas = 1st Class

Ldst = landstormsoldaat

tkl = tweede klas = 2nd Class

Man = Menadonees = From Menado

korp = korporaal = Corporal

Amb = Ambonees = From Ambon

zvpl = ziekenverpleger = Male Nurse/Orderly

Mlt = militie = Militia

sld = soldaat = Private

Snd = Soedanees = From Soenda

fus = fuselier = Fusilier

Interestingly, looking at the Dutch list, there are no Engineers.

Missing from the KNIL list is Cornelis Gerrit van Rossum of the Royal Dutch Engineers. He was at the Dutch HQ in Dilly/Dili as a telephonist on 20 February 1942. On 15 June 1942, he was still in East Timor as a radiotelegraphist. We think he escaped to Australia or was transferred due to injury. According to his granddaughter (a Major in the Dutch army), he was part of the Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service, but she isn’t sure. Also missing from the KNIL list is Sergeant Dijkhuis.

As far as known, the following personnel escaped to Australia:

- Dutch Engineers were placed in the 18 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron and trained at the RAAF Airbase Fairbairn in Canberra for ground staff duties.

- Soldiers of the Infantry and Artillery were stationed at ??

According to the report of Ponggohon and Tasmin:

- About 24 men were killed when the Armidale was torpedoed and sunk. Names include Teljeur, Keijzer, and Soewondo.

- In the sloop were 4 (wounded) KNIL soldiers (Ponggohon, Tasmin, Toeroet, and Sirin; Sirin died).

- On the raft were 8 KNIL soldiers (Stoll, Bodel Bienfait, and Frank), and on another raft made of two long iron cylinders, there were 30 men.

The Armidale at the Australian War Memorial.

Below a very famous picture of the Armidale which is on display in the Australian War Memorial. Pictures by Paul Budde April 2024.

Medical Officer Roelof Frank one of the victims

An interesting yet disturbing footnote for me (Paul Budde) was the involvement of one of the medics who was among those drowned. He was a GP at my hometown of Oss. Dr. Roelof Frank was called up for military service in February 1940 and stationed near Hoek van Holland. He crossed over to England with the Dutch Royal Family and the remnants of the Dutch army in May 1940. He worked as Medical Officer at Clapham Hospital, London, at Porthcawl and in Yorkshire. Sent to Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1941, he served in the British army there. He made three convoy runs on hospital ships between Colombo and Melbourne, Australia. Returning to Colombo on the HMAS Armidale he became one of the victims of the air raid. The story has some further interesting and disturbing elements to it.

Dr. Frank was Jewish, during WWII his wife Betty and her mother, transformed their house and practice in Oss into a refuge called “Rusthuis Hannah” for the remaining sick and elderly Jews in the town. However, they fell victim to betrayal. “Jew hunters,” incentivised by bounties, captured them, and subsequently, the last Jews from Oss were transported to the extermination camps. Remarkably, this occurred on the same day that Anne Frank and her family in Amsterdam were also rounded up, marking a parallel and dreadful fate.

Betty Frank-Mayer and her family however, had been able to go into hiding before all of that happened. After the liberation of the southern Netherlands, they returned to Oss but refused to accept the death of her husband . “You cannot possibly know, until the war with Japan has ended, whether he could have saved himself on some island in the Timor Sea, whether occupied by the Japanese or not,” she wrote to the War Ministry. In 1946, Roelof Frank was nevertheless officially declared dead.

His wife, son and parents-in-law can return to the former “Rusthuis Hannah”. In 1951, Betty emigrates to South Africa with Joachim and her parents. She died in 1985 in Johannesburg. Joachim currently (2024) lives in London as a retired gynecologist. Author: Twan van den Brand. Source: Brabants Erfgoed.

See also:

The Sinking of HMAS Armidale on 1 December 1942

Het verdwenen KNIL-regiment van de Armidale (in Dutch) The lost KNIL regiment of the Armidale