Charleville, in western Queensland, is often remembered for its role as a major American base during the Second World War. Less well known is the town’s connection to the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) through the Dutch airline KNILM (Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij). For a brief but critical period before and during the Pacific War, Charleville was also a lifeline between Batavia and Sydney, and a staging point in the Dutch evacuation to Australia.

KNILM and the pre-war service

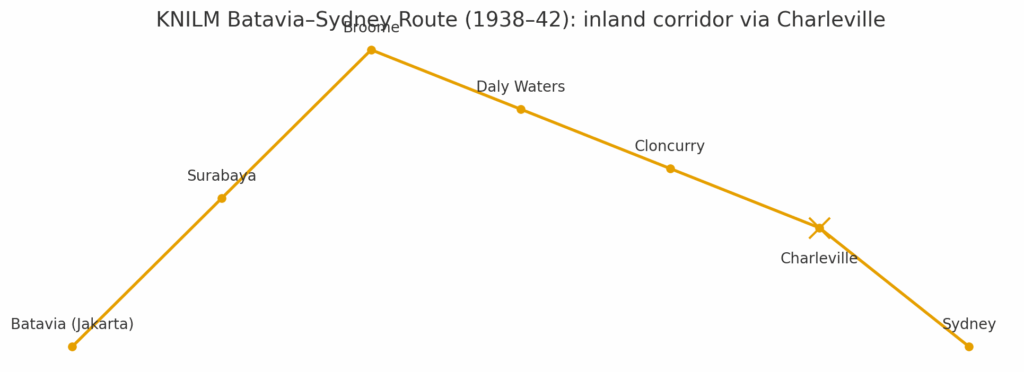

In July 1938, KNILM launched a regular passenger and mail service between Batavia (Jakarta) and Sydney. The route ran inland across northern and central Australia, stopping at Darwin – Cloncurry – Charleville – Sydney. Charleville was the final inland refuelling stop before aircraft reached Sydney. Its long runway, Shell refuelling facilities, and role in Qantas’s inland network made it an ideal staging point. Weekly services linked the Netherlands East Indies and Australia, strengthening civil and diplomatic ties at a time when the looming threat of war in Asia was already apparent.

| Shell Australia’s role in Charleville added another layer to the Dutch connection. As KNILM’s aviation fuel supplier, Shell maintained depots at inland airfields such as Charleville, ensuring that Dutch aircraft could operate regular services before the war and later support emergency evacuation flights in 1942. In this way, Dutch corporate presence was embedded in the town’s wartime aviation history, linking Charleville not only to the Netherlands East Indies through KNILM but also to the global Shell network that sustained these critical air routes. |

Charleville as a wartime link

The outbreak of war in the Pacific turned Charleville from a refuelling stop into part of a desperate evacuation corridor. In February 1942, as Japanese forces advanced through the East Indies, KNILM aircraft were commandeered for military use. Flights carried Dutch government officials, archives, military cargo, and hundreds of KNILM staff and their families out of Java. The evacuation route typically ran Batavia – Surabaya – Broome – Daly Waters – Cloncurry – Charleville – Sydney.

Aircraft often left Batavia in the night, staggered an hour apart, and landed in Charleville before completing the final leg to Sydney. After unloading, the planes would turn north again to collect more passengers and equipment, establishing a pendulum service that kept a tenuous line open between Java and Australia until the NEI fell to Japanese occupation.

In all, eleven KNILM aircraft managed to escape to Australia. Around 200 airline staff and families were evacuated, alongside government personnel and sensitive cargo. Charleville was an essential waypoint in this air bridge. For local residents, the sight of Dutch aircraft and evacuees passing through became a vivid reminder that the war in Asia was now linked directly to inland Queensland.

Military aircraft and Dutch forces

Charleville’s wartime role expanded when the airfield became a USAAF Aircraft Reception Depot, handling streams of aircraft flown across the Pacific. Several Dutch aircraft stranded in Australia after the collapse of the NEI were absorbed into Allied service. Bombers purchased by the Netherlands for use in the Indies, which arrived in Australia too late, were transferred to the USAAF. It is highly likely that many of these aircraft also passed through Charleville as part of their delivery and redistribution.

At the same time, surviving Dutch aircrews regrouped in Australia. The most significant outcome was the creation of No. 18 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron RAAF in April 1942. Operating B-25 Mitchell bombers, the squadron flew from bases such as Batchelor conducting raids across the occupied Indies. While Charleville was not a permanent base for Dutch squadrons, its role as a transport and ferry hub made it part of the wider Dutch–Australian military aviation network.

The “Pelikaan” and other KNILM aircraft

One of the most famous KNILM aircraft was the DC-3 “Pelikaan”, known for its record-breaking Amsterdam–Batavia flight in 1933. The aircraft survived into the war years and was among those evacuated to Australia. Whether the Pelikaan itself landed at Charleville has not been conclusively confirmed, but given the established KNILM evacuation routing via Charleville, it is very likely that it did. Archival flight logs or local newspapers may yet provide confirmation of its passage through the town.

Aftermath and legacy

By the time Dutch operations were reorganised in Australia, Charleville’s role as a staging post had begun to fade. KNILM’s head office was relocated to Sydney, where surviving aircraft underwent maintenance and were pressed into Allied service. Many of the airline’s senior staff gathered in the Australian Hotel in Sydney, while their aircraft were scattered across the country and commandeered for military transport. The Dutch civilian airline had effectively ceased to exist, transformed into part of the Allied war machine.

Yet Charleville’s place in this story should not be overlooked. For a critical few years, it was a key junction in the skies between Java and Sydney, carrying evacuees, archives, and aircraft into Australia. It was also a waypoint in the redistribution of Dutch bombers and transports that would go on to serve under American and Australian command. The Dutch presence in Charleville highlights how even inland Queensland towns became tied to global events, their airstrips linking local communities to the war in Europe and Asia.