The submarine service of the Royal Netherlands Navy (RNN) was established in 1906. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the Netherlands operated approximately 25 submarines, of which around 15 were deployed in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). These boats formed the core of Dutch naval resistance against the Japanese advance across Southeast Asia in 1941–42.

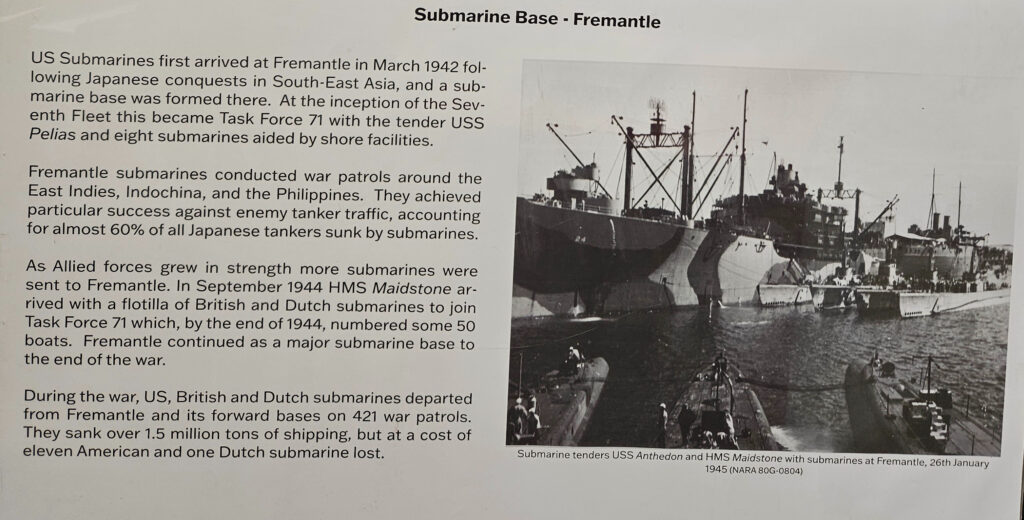

Following the collapse of Allied defences in the NEI and the fall of Java, a small number of surviving Dutch submarines escaped to Australia or Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). From 1942 onward, Australia—particularly Fremantle in Western Australia—became the principal base for Dutch submarine operations in the South-West Pacific.

Although several Dutch submarines reached Australia following the fall of the Netherlands East Indies, their operational effectiveness was constrained by technical and logistical realities. Most of the boats available in Australian waters—such as K-VIII, K-IX and K-XII—were already nearing the end of their service life. With the Netherlands occupied and Dutch naval dockyards in the NEI lost, spare parts were largely unobtainable. Components often had to be manufactured locally, resulting in prolonged repair periods. As a consequence, some submarines spent more time in dry dock than on patrol, limiting the scale and tempo of Dutch submarine operations from Australia.

This overview draws primarily on the research of Dr Jack Ford, especially his doctoral work Allies in a Bind, which remains the most detailed study of Dutch naval reorganisation and operations in Australia following the fall of the NEI. Ford’s research provides the principal analytical framework for the Dutch submarine narrative presented here. It is complemented by Australian-based research, including Lynne Cairns’ Fremantle’s Secret Fleets, and by Dutch and Australian archival material.

Submarine successes in the opening phase of the Pacific War

In the opening weeks of the Pacific War, Dutch submarines achieved a level of success disproportionate to the size of the force. Operating in forward waters off Malaya, British Borneo and the approaches to Java, they sank or severely damaged Japanese troop transports, tankers and escort vessels at a time when Allied surface fleets were increasingly neutralised by Japanese air power.

For a brief but critical period, Dutch submarines inflicted heavier shipping losses on Japanese invasion forces than either British or American submarines operating in the same theatre. These actions disrupted invasion schedules, forced Japanese convoys to divert, and demonstrated the effectiveness of the Royal Netherlands Navy’s pre-war doctrine of coordinated air–submarine operations. This early record of success earned Admiral Conrad Helfrich his reputation and later drew Allied interest in Dutch submarine tactics, even as Dutch operational control was subsequently constrained under Allied command arrangements.

The short-lived ABDA command and its consequences

In January 1942, as Japanese forces advanced rapidly across Southeast Asia, the Allied powers established the American-British-Dutch Australia (ABDA) Command in an attempt to coordinate the defence of Malaya, Singapore and the Netherlands East Indies. ABDA was conceived as a unified command, but in practice it proved short-lived and was hampered by conflicting strategic priorities, incompatible doctrines, and severe coordination and communication problems.

For the Dutch submarine force, the creation of ABDA marked a decisive turning point. Pre-war Dutch doctrine relied on close coordination between naval air reconnaissance and submarine attack groups. Under ABDA, Dutch submarines were increasingly deployed on solitary patrols, often in unfamiliar waters and without adequate air support. This significantly reduced their effectiveness and contributed to mounting losses during the defence of Malaya and the NEI.

The short-lived ABDA Command provided the initial framework for Dutch submarine deployments in early 1942, but its rapid collapse left surviving Dutch naval forces operating within fragmented Allied command structures.

ABDA collapsed within weeks following the fall of Singapore and the defeat of Allied naval forces in the Java Sea. Its failure left the remaining Dutch submarines without a coherent operational framework and directly influenced the decision to evacuate surviving vessels to Australia, where they were later reorganised under new Allied command arrangements.

Collapse of the NEI and escape to Australia

After the Battle of the Java Sea and the rapid Japanese advance on Java, Dutch naval units were ordered to evacuate in early March 1942. Seven submarines, together with a limited number of surface vessels and auxiliaries, managed to escape. Many other ships were scuttled at Surabaya to prevent capture.

Destruction of the RNN Naval Base of Surabaya

| On 8 March, the Japanese finally entered Soerabaja, to find it ablaze due to “the incendiarism carried out by the retreating Dutch troops.” The harbour was full of scuttled ships, including Soerabaia, Serdang, destroyers Stewart, Banckert, submarines K-X, K-XIII, K-XVIII, minelayer Gouden Leeuw (1,291 tons), 10 minesweepers, 5 patrol vessels and 13 motor torpedo boats. An unfinished sloop and 12 motor launches were destroyed on the stocks. Survey vessel Willebrord Snelluis (930 tons) was sunk as a blockship. Following his Governor-General’s advice, ter Poorten declared Bandoeng an open city and sent emissaries on the Bandoeng-Kalidjati Road towards the enemy. The Dutch forces were ordered to surrender at 10 am on 9 March. |

Fremantle as a Dutch submarine base

Fremantle became a primary destination for these escaping vessels. As the nearest major Allied port on the escape route from southern Java, it rapidly filled with Dutch warships, merchant vessels and evacuees. By early March 1942 the concentration of Dutch shipping was so noticeable that local wharf labourers reportedly referred to them as “the Flying Dutchmen”.

From mid-1942 onward, Fremantle functioned as the principal Dutch submarine base in Australia. Dutch submarines operating from Fremantle came under the operational control of the United States Navy’s submarine command in the South-West Pacific Area, led by Rear-Admiral Charles Lockwood.

Already on January 1 , 1942 Rear Admiral Frederik Willem Coster was asked to come out off retirement and was put in charge of the Purchasing Commission In Australia, as the Netherlands and Netherlands East Indies were no longer able to supply the products and services needed for the military.

Following the Fall of NEI which led to the escape of military personnel, planes and ships to Australia Helfrich appointed him as the Commander of the Dutch Naval Forces in Australia in charge of reorganising the Dutch Navy. He was later replaced by Commander Pieter Koenraad.

The Dutch submarines were placed under Allied operational control, primarily through the United States Navy’s submarine command in the Southwest Pacific Area. While the submarines remained Dutch-manned and administratively part of the Royal Netherlands Navy, operational tasking fell under U.S. command, notably that of Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood. Dutch requests to place submarines dedicated to intelligence work under direct Royal Netherlands Navy operational control were declined, as this was considered incompatible with Allied command protocols. This division between administrative responsibility and operational authority affected deployment priorities and limited Dutch autonomy in directing submarine missions.

In practice, operations were constrained by the age and condition of the surviving Dutch submarines. Most had been built in the 1920s and early 1930s and suffered from chronic mechanical problems. Spare parts were difficult or impossible to obtain, forcing local manufacture or lengthy repairs. Depot ships such as Plancius and Ondina provided essential support, while refuelling often required the use of Exmouth Gulf.

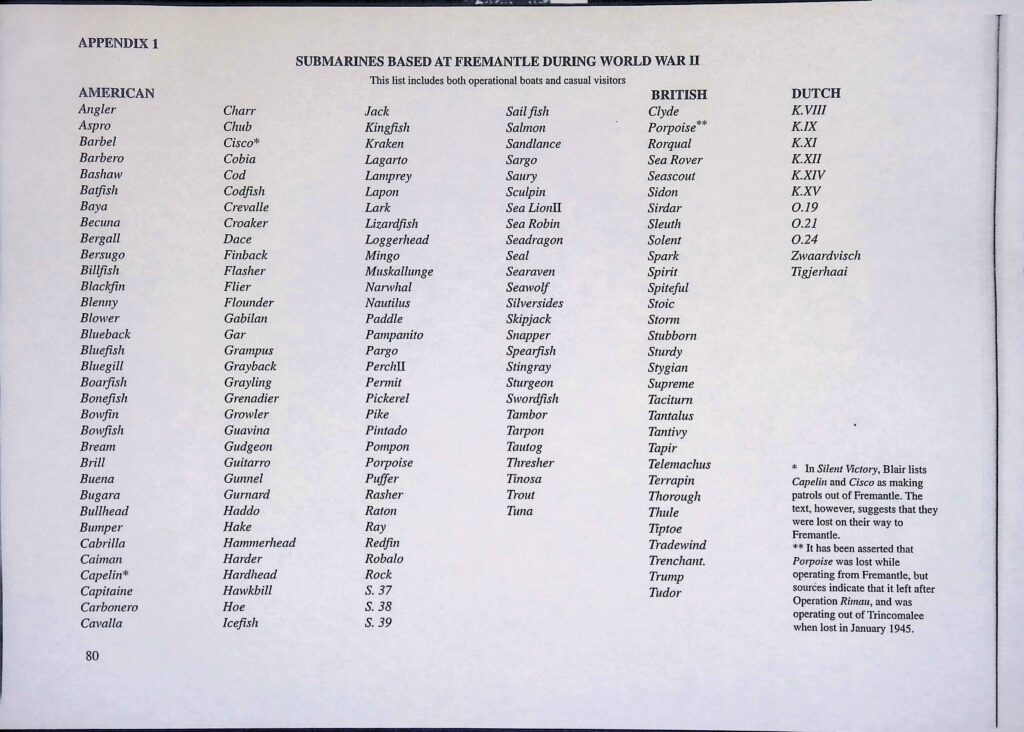

Despite these limitations, Dutch submarines continued to operate alongside American and, later, British boats from Fremantle and formed a distinct component of the Allied submarine effort in the Indian Ocean and surrounding seas.

The above images are from the submarines used by the RNN. Zwaardvisch and Tijgerhaai, were temporarily transferred by the RN to the RNN. The last three pictures are from the depot ships that supported the submarines. Images are from the RNN and the National Archives.

Submarines, NEFIS and NICA operations from Australia

As conventional naval resistance became impossible after the fall of the NEI, Dutch submarines assumed a critical role in intelligence and special operations. Working in support of the Netherlands East Indies Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS), submarines operating from Australia were used to insert and extract agents, transport personnel and equipment, and conduct covert reconnaissance in Japanese-occupied territory.

These operations were coordinated from Australia, with NEFIS headquarters located at Camp Columbia in Brisbane. Submarine-supported intelligence missions provided vital information on Japanese troop movements, installations and logistics across the archipelago, particularly in Dutch New Guinea and eastern Indonesia.

Submarine activity also intersected with the work of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA), which was preparing for post-war reoccupation and administration. Intelligence gathered through submarine-delivered missions informed Allied operational planning and shaped Dutch political expectations regarding the restoration of authority in the NEI. Despite chronic mechanical problems and a shortage of suitable boats, submarines remained the most secure and discreet means available to the Dutch for penetrating Japanese-controlled waters.

Reinforcements and late-war operations

In 1944, the Dutch submarine force in Australia was reinforced by two modern submarines transferred from the Royal Navy: Zwaardvisch and Tijgerhaai. Operating from Fremantle, these boats conducted patrols in the Java Sea, the South China Sea and surrounding waters as part of an Allied submarine flotilla.

Dutch crews earned a strong reputation among their Allied counterparts for professionalism, resilience and operational skill. Although operating within Allied command structures dominated by American and British priorities, Dutch submariners continued to make a meaningful contribution to the disruption of Japanese shipping and to the intelligence campaign in the later stages of the war.

Individual submarines and further reading

This hub article is supported by a number of more detailed DACC publications, which explore specific aspects of the Dutch submarine story in greater depth:

- Dutch submarine tactics in Allied strategy: ignored, copied and overshadowed

- Dutch submarine K-IX and the Japanese attack on Sydney Harbour

- The rediscovery of HNLMS K-XI near Rottnest Island

- Dutch WWII submarines in Australia, including the post-war fate of K-XII

Together, these articles provide tactical analysis, vessel-specific histories and modern heritage perspectives that complement this overview.

Wreck protection and legacy

Many Dutch submarines lost during the war now lie in Southeast Asian waters and are recognised as war graves. Recent maritime archaeological expeditions have confirmed that several wrecks have been illegally salvaged, while others remain intact but vulnerable. These sites represent both the sacrifice of Dutch crews and a largely overlooked chapter of Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation.

Conclusion

Dutch submarines played a critical role in the early defence of Southeast Asia, the transition of Allied naval power to Australia, and the intelligence war that followed. Their early successes, the disruption caused by the failure of ABDA, and their later adaptation to intelligence and special operations illustrate both the strengths and constraints of Dutch naval power in exile.

Operating from Australian ports, particularly Fremantle, Dutch submarines became part of a wider Allied effort linking Australia, the Netherlands, the United States and Britain. Their contribution, though often overshadowed in mainstream histories, remains a significant element of Dutch–Australian wartime cooperation.

Paul Budde (December 2025)

Personal stories

Jan Leenhouwers – sailor on the Zwaardvisch

| Johan Cornelis Leenhouwers was born in Tilburg on the 27th November 1919, out of wedlock. He was formally adopted into the marriage of his mother to another gentleman on the 26th of November 1921.He joined the Dutch navy before WW2 as an electrical mechanic on the submarines and I believe the submarine he was on, was one of the last to sail out of Holland as the Germans over ran Holland. He spent time in the UK before his submarine sailed to Columbo. From Columbo the submarine he was on then relocated to Fremantle for the later part of the war. I believe my father was transferred from his submarine that was about to sail to the US for a refit to another Dutch submarine. My understanding was that this was due to my fathers’ insubordination to his commanding officer.My father married an Australian woman and after the war, they relocated back to Holland. The family them emigrated to Australia with my father and older brother (born in Holland) arriving in Perth on February the 4th 1949. See additional link https://immigrantships.net/v5/1900v5/volendam19490204.htmlI have recollections of WW2 stories that my father told me, however these are rather vague as dad never really went into any details. I know my older sister would have additional information; however, I hope this may be enough to start with at this stage. I do have some of his documents and medals in my possession and will endeavour to locate them for reference.Peter Leenhouwers (his son) |

Submarine casualties

Elsewhere we cover the story of Henk Paardekooper.

Two friends of the Paardekooper family lost their lives in Dutch submarines in the war with Japan:

Joop van de Klift died on the O-16

Kees Prins with – as it turned out – the last Dutch submarine, which went down in the war.

At the last meeting, of several of them during the war, Kees told Henk Paardekoper: he was convinced that this would be his last trip and he left his paybook and some silverware with Henk in Brisbane. This was after the war given to his parents in the Netherlands. Henk’s daughter Henny was present and has a ‘Djokja’ silver basket, which Kees’ parents gave back in gratitude to Henny.

Hette Kingsma (Henny’s husband)