Pierre van der Eng

Sydney had two Dutch hospitals during 1944-1946. Both were related to the presence in Australia of a growing number of people from colonial Indonesia during 1942-1945.

Since March 1942, officials of the government the Netherlands East Indies left Indonesia for Australia before the Japanese occupation of the country. They were joined by many others who also escaped Japanese capture or were dispatched by the Dutch government in exile in London. By 1944, most were part of the colonial government’s armed forces preparing to roll back the Japanese presence, starting in Eastern Indonesia. Others prepared the relief efforts and the return of the civil administration to Indonesia.

Included in this growing Dutch-Indonesian group in Australia were sailors of the 21 merchant ships of the Royal Packet Navigation Company (Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij, KPM) that in 1942 escaped to Sydney. The KPM Sydney office had previously arranged freight and passenger transport on KPM’s Java-Australia and South Pacific lines. The colonial government in exile made the office responsible for these 21 vessels and for 210 other Dutch merchant ships in the region (Bakker 1950: 168). Together with its new sub-offices in Melbourne and Brisbane, KPM office personnel increased from 40 in 1942 to 162 in 1945 (Bakker 1950: 150).

These ships plied routes from Australian ports across the Pacific in support of the Allied war effort. They shipped cargo, military supplies and Australian, American and later NEI troops. KPM passenger ships, such as the MS Oranje, SS Tasman and MS Maetsuyker, were converted in Australia to hospital ships. They brought wounded from the wars in the Middle East, Pacific or Southeast Asia to Sydney. The ships also delivered relief supplies that were stockpiled in Australia for eventual delivery in Indonesia. Most of the sailors on these ships had Dutch identity papers but were of Indonesian, European or Indian ethnicity.

The KPM Sydney office was responsible for about 2,600 sailors: 600 Dutch and 2,000 ethnic Indonesians (Mulder 1991: 30). They would generally be at sea. When in port in Australia, they were part of the estimated 7,000 to 8,000 Dutch and Indonesian evacuees from Indonesia who lived in Australia during the war years (Rozeboom 2022: 72).

Medical facilities

KPM ran two occasional medical clinics in the Belvedere guesthouse in Darlinghurst since June 1942 and in the Lido Hostel in North Sydney since June 1943. Both were shared accommodation leased by KPM for Indonesian and Indian sailors. With the growing Dutch-Indonesian population in Sydney, the colonial government in exile in 1943 required more permanent medical services, particularly for the sailors.

One reason was to relieve the war-stretched Australian medical services, another was to provide Indonesians and Dutch with nursing staff who were able to speak Indonesian or Dutch, and with Dutch-trained medical staff for treatment. But the main reason was that, when in port, the crews of the Dutch ships needed onshore medical treatment and recuperation. For that reason, the colonial government in exile asked the KPM in 1943 to support the establishment of Dutch medical facilities in Sydney (Rozeboom 2022: 150.)

Source: National Archives of Australia, SP11 2 DUTCHLEENT J P V

After the Australian government gave the requires permissions in mid-1943, preparations to establish three medical facilities started. Johan Philip van Leent (1905-1960), a 1936 medical graduate from Leiden University and a military doctor was in charge. He had arrived in Australia from Indonesia in 1942 and was appointed medical superintendent in charge of the design and operation of these facilities.

One facility was a medical clinic, located in offices leased by KPM. First along Sussex Street, later Lennox Street, before Kent Street. It became known as the Oranje Clinic that operated between 22 November 1943 and 30 August 1946 (Mulder 1991: 30.) The clinic was managed by Edith Kranendonk (1914-1949), a trained nurse who had escaped the German-occupied Netherlands in 1942. The Dutch government-in-exile had dispatched her from London. She arrived in Sydney in November 1943 as an officer in the Medical Service of the government of colonial Indonesia.

If necessary, the clinic referred patients for further treatment to the Queen Wilhelmina Hospital. It was located in a large KPM-leased former boarding house at 4 Martin Road at Centennial Park, leased. It operated between 27 January 1944 and 15 January 1947. Eight temporary fibro-asbestos cottages with two to nine rooms each were built in the large garden of the property, which functioned as additional hospital wards.

The third facility was the purpose-built Princess Juliana Sanatorium Hospital situated on a large block of land along Bobbin Head Road in then still very rural Turramurra near Wahroonga. It was a refuge for revalidation, particularly of KPM sailors suffering tuberculosis (TB). It operated 28 December 1943 to 22 August 1946.

The first manager of the Juliana hospital was Sarosan (1906- ), assisted by his wife Lasmikin (1911- ). Sarosan had trained as a nurse in Semarang hospital in Java (Shiraishi 2021: 146-151). As an active communist, he had been exiled to Upper Digul in New Guinea in 1931, from where he had arrived in Australia in 1943 as a political detainee. He took the hospital job on his release in April 1944. The Juliana hospital also had four other Indonesian nursing staff.

The Juliana hospital had 66 beds with a separate section for women. Most patients were Indonesian KPM sailors, but the hospital also treated other medical cases. For example, in 1944 one of the patients was a woman who had escaped from Surabaya in a fishing boat, while the youngest patient that year was a 6-week-old baby from Java.

Medical staff

In addition to Van Leent, Levie Polk (1897-1975) was the second medical doctor on duty at these medical facilities. Polk was a medical graduate from the University of Amsterdam, who had migrated to Australia from Surabaya in 1941. The colonial government in exile also employed medical doctor Raden Ma’amoen al Rasjid Koesoemadilaga (1901- ). However, he served as chief administrator of the colonial government’s Medical Service. Only Van Leent and Polk received dispensation from the NSW Medical Board to practice medicine (Weaver 2009: 28-29).

Most employees at the three medical facilities were nurses and trainee nurses, male and female. Among the male nurses at the two hospitals were ethnic Indonesians Doelrachman and Misar. These facilities doubled as a nurses training school for females recruited from arrivals from Indonesia and from the local Dutch community in Australia. The recruited nurses served in the medical corps of the Netherlands Indies army and included both Dutch nationals and ethnic Indonesians who also had Dutch citizenship.

Several of the nurses trained in the three facilities later moved to Indonesia in the service of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) to work in areas recovered from the Japanese. For example, sergeant Leah Jas née Kaneaf (1922- ) from Queanbeyan had married Dutch corporal Henricus Jas in Australia in 1942. She volunteered as a Dutch citizen, learned Dutch and Indonesian and served as a nurse’s assistant. Sergeant Ineke Thijsse (1922-2017) had arrived from Java in 1941 to study architecture at the University of Sydney and volunteered after 3 years of study. There were also Australians working as nurses at the Queen Wilhelmina hospital, such as Sheila Kearns and Marjorie Whiteman.

Patients

Source: Daily Telegraph, 1 August 1944.

The Wilhelmina hospital offered general health services for Dutch and Indonesians and their families. In mid-1945 the hospital also accommodated convalescing KPM sailors suffering from TB. And in 1946 it even provided obstetrics, because a Javanese baby was born there.

The Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945 was not the end of the 2 hospitals. During September 1945 to April 1946 the hospitals were also used for the recuperation of Dutch nationals after their release from Japanese detention camps in Indonesia. For example, in 1946 Mrs G. Laterveer recuperated in the Wilhelmina hospital after 3.5 years in detention in Jakarta.

The Juliana hospital continued to accommodate Indonesian sailors until they could be repatriated to Indonesia. For example, seaman Wallay Wahab from Surabaya lived at the Juliana hospital in November 1945 when he mistakenly believed to have won 10,000 pounds in a lottery.

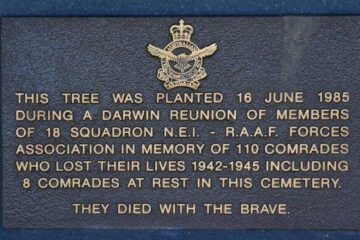

Patients who died in Sydney

Not all patients staying at the two hospitals survived. The Dutch war graves foundation recorded 31 sailors who died in Sydney during 1943-1946; 20 of them were of Indonesian ethnicity, 3 were Indian Muslims, 5 Dutch, 1 from Surinam, 1 from The Netherlands Antilles and 1 British. For example, Amos Djoega from West Timor, a sailor from the SS Tasman, died in the Wilhelmina hospital in November 1944, or Goenar from Wonosari (Java), an oiler on the MS Maetsuycker, died in the Princess Juliana Sanatorium in January 1945. Both were interned in the necropolis of Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney. The last Dutch sailor to die in Sydney was Hendrik Hogenbijl. He had had survived as POW in Burma after serving in the Dutch Navy, joined the KPM, fell ill at sea, died in Sydney in April 1946 and was buried in Rookwood Cemetery.

Two prominent Wilhemina hospital patients who died in Sydney were Raden Loekman Djajadiningrat (1891-1944) and Petrus Sitsen (1885-1945). Both were high-placed NEI public servants who had arrived in Australia in March 1942, fleeing the Japanese occupation of Java, to become part of the NEI government in exile.

Djajadiningrat was an engineering graduate of Delft University, who had made a career in the Department of Education in the 1930s. In Australia, he was appointed Director of Education in 1943. He died of heart disease in July 1944. His body was transported to Merauke in West New Guinea, from where it was brought to Jakarta in 1953 for burial in the family vault.

Sitsen was a public servant in the Department of Economic Affairs in charge of small-scale industries in the 1930s. In Australia, he was tasked with coordinating the postwar humanitarian relief effort and economic recovery. He died in January 1945 and was buried in Sydney’s Northern Suburbs Cemetery.

Winding up

Following the Japanese surrender, the colonial government in exile and most Dutch and Indonesians in Australia repatriated to Indonesia in the course of 1945 and 1946. The two hospitals remained operational to allow the recuperation of remaining TB patients and former detainees from Japanese camps in Indonesia.

KPM cleared and closed the Oranje clinic in August 1946. The Queen Wilhelmina Hospital was still operational in October 1946, when Henk de Vos and his wife Conny ‘Pop’ Moed Helmig from Batavia welcomed the birth of their daughter Joan. The building was vacated soon after. Together with the eight temporary cottages in the gardens of the property, the building was auctioned in February 1947.

The colonial government sold the Princess Juliana Hospital to the NSW government in July 1946. Its representatives in Sydney intended to move the last group of 25 TB patients during August 1946 to a ward at the Queen Wilhelmina hospital in Randwick. There they would await repatriation to Java by the KPM hospital ship SS Tasman at the end of August, where Minister for Health of the new Republic of Indonesia had agreed to accommodate them for further recuperation.

But the closure of the Juliana hospital became a political controversy, when on the day of their removal, 21 August 1946, the 25 patients refused to being moved to Randwick (Lingard 2008: 219-222, 297-298). They argued that TB is a contagious disease and TB patients should not mix with other patents. About the Queen Wilhelmina facility, they stated: ‘We would prefer to die rather than go there, as our treatment would be very bad.’ Even though Polk assured them: ‘We have a special ward waiting for the men and have cooked special food. The same authorities run the sanatorium as the hospital and Indonesians will have the same staff.’ And ‘Treatment of Dutch and Indonesians in the hospital is exactly the same.’ Except that the ward was staffed with Indonesian nurses from the Juliana hospital.

The reason for the obstinance of the 25 sailors was that the Indonesian Independence League in Australia and the Indonesian Seaman’s Union were able to use their case to draw attention to the fact that Indonesia had declared its independence. They assisted the transfer of the sailors to downtown Sydney, where they squatted in the unoccupied Oranje Clinic along Kent Street.

After the owner of the building started a court case against locating the TB suffering sailors in the hospital, the judge imposed an injunction and it became impossible to move the sailors to the Wilhelmina Hospital. In December 1946, the sailors were still in the former Oranje Clinic. They eventually joined hundreds of other Indonesians repatriated on Australian ships during 1947.

Princess Juliana Hospital site

Despite its sale to the NSW government in mid-1946, the destiny of the Juliana hospital remained unclear. In January 1947 the NSW Red Cross offered to buy it to establish a TB sanatorium, as TB was still a prevalent disease in NSW and waiting lists for existing sanatoria were long. In March 1947 a private initiative wanted to acquire the hospital and convert it to a rheumatic disease hospital. In December 1948 the Federal government acquired the facility to turn it into a home for 100 war orphans from displaced person’s camps in Western Germany awaiting their adoption in Australia.

In 1950 the NSW government took charge of the Juliana hospital to re-establish it as an initially 50-bed TB sanatorium. It would be extended with additional buildings as the Princess Juliana Chest Hospital for Migrants. In 1951 it became a subsidiary of the Thoracic Unit of the Royal North Shore Hospital.

The facility continued to operate under the name Princess Juliana Hospital as a TB sanatorium for immigrants until 1970 and as a nurses training school until 1977, after which the building were demolished. The Hornsby and Kur-ring-gai Senior Citizens Care Association built the Princess Juliana Lodge retirement home on the site of the Juliana hospital in Turramurra, which opened in 1982.

Medical staff who stayed

Several of the medical staff of the three Dutch medical facilities remained in Australia after 1946. Edith Kranendonk established herself as a chiropodist in Southport (Qld) but died soon after in 1949 at the Royal Prince Afred Hospital in Sydney. She was buried in the Church of England Cemetery in Botany (now Eastern Suburbs Memorial Park).

After leaving the military in March 1949, John van Leent became an Australian citizen and medical superintendent at the Bathurst immigration camp. He later established his own medical practice in Paramatta. Levie Polk established his own medical practice in Double Bay. Until their deaths, GPs Van Leent and Polk were both well-known in the growing community of Dutch migrants in Sydney.

References

Bakker, H.Th. (1950) De K.P.M. in Oorlogstijd: Een Overzicht van de Verrichtingen van de Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij en Haar Personeel Gedurende de Wereldoorlog 1939-1945. Amsterdam: J.H. de Bussy.

Lingard, Jan (2008) Refugees and Rebels: Indonesian Exiles in Wartime Australia. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Mulder, A.J.J. (1991) Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij: Wel en Wee van Een Indische Rederij. Alkmaar: De Alk.

Rozeboom, Judith Mirjam (2022) Merdeka Down Under? Indonesian Civilians and Military Personnel in Australia (1942–1949). PhD thesis, University of Sydney.

Shiraishi, Takashi (2021) The Phantom World of Digul: Policing as Politics in Colonial Indonesia, 1926-1941. Singapore: NUS Press.

Weaver, John (2009) ‘“A Glut on the Market”: Medical Practice Laws and Treatment of Refugee Doctors in Australia and New Zealand, 1933-1942.’ Australia & New Zealand Law & History E-Journal, Refereed Paper No 2.