On the eve of the Netherlands East Indies’ capitulation, a series of evacuation flights brought Dutch citizens to the safety of Australia, with Broome emerging as a key evacuation hub. Among the heroic pilots, Dutch-Russian Captain Iwan Smirnoff stood out for his multiple successful evacuation missions, regarding it as a routine endeavour (the milk-run as he called it).

on March 3, 1942 he again departing from Andir near Bandung in the DC3 ‘Pelican’ (Pelikaan). His plane took off at 1:15 am, in the midst of a torrential tropical rainstorm with powerful gusts.

Alongside Smirnoff were three dedicated crew members: co-pilot Johan Hoffman, Flight Engineer Joop Blauw, and radio operator Jo Muller. Accompanying them were eight passengers, including Lieutenant Pieter Cramerus (on his way via Australia to the Dutch Flying School in Jackson, Mississippi) , air force pilot Daan Hendriksz, naval pilot Dick Brinkman, naval pilot Heinrick Gerrits, KNILM student Hendrick van Romondt, sergeant pilot Leon Vanderburg, and the mother-son duo of Maria van Tuyn and 1-year-old Johannes, reuniting with Maria’s husband already in Australia. To conserve weight, there were no seats in the evacuation plane, prompting everyone to sit on the wooden floor.

As the DC-3 neared Broome after a seven-hour flight, the radio operator, John ‘Jo’ Muller, received reassuring news that the runway was clear. However, about 80 kilometers from their destination, they spotted thick plumes of smoke billowing up from Broome. Unbeknownst to them, nine Japanese Zeros, accompanied by a Mitsubishi C5M2 commando scout from the 3rd AG in Koepang, Timor, had attacked Broome. Dutch flying boats carrying evacuees were in Roebuck Bay, adding to the calamity. Tragically, 51 lives were lost, with several never recovered. Not limited to Dutch aircraft, the Zeros also targeted other Allied planes in the bay and at Broome airport. A B-24 Liberator, just taking off from Broome, plunged into the sea following a Zero attack, leaving only one survivor.

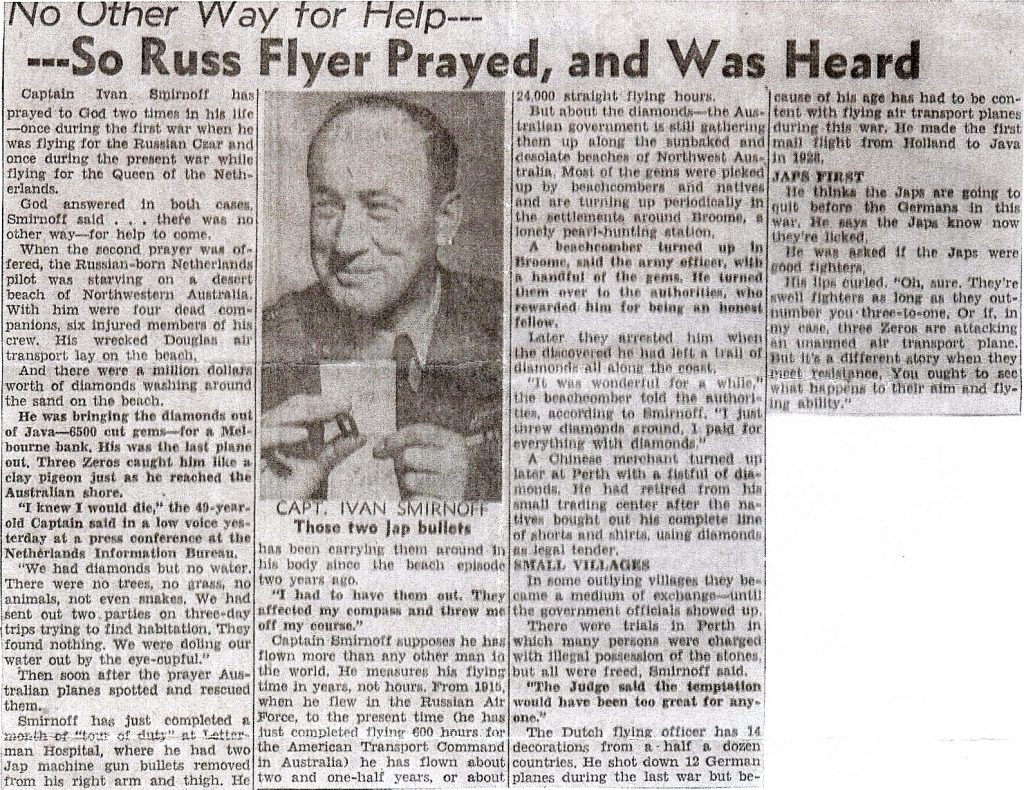

Three Zeros, responsible for guarding the six attacking planes, viewed Smirnoff’s DC-3 as an easy target and initiated an assault from the port side. Bullets pierced the thin aluminium skin, wounding Smirnoff in the arm and hip.

Nevertheless, Smirnoff skilfully manoeuvred the plane into a steep descent, pursued by the Zeros. Tragedy struck inside the cabin as Maria van Tuyn was struck in the back, suffering severe injuries. Sergeant Leon Vanderburg quickly shielded Maria’s child, Johannes, using his own body as protection, but both sustained injuries. Another passenger, Daan Hendrikz, was also hit and lost consciousness.

The port engine caught fire, and the crew feared the flames would soon reach the fuel tanks. Fearing an explosion, Smirnoff made the decision to land the plane as swiftly as possible. The best option was a landing on Carnot Bay’s beach. The landing gear descended to a mere 60 meters. With a crashing sound, the starboard wheel broke, possibly struck by Japanese fire, causing the plane to veer sharply right through the surf, extinguishing the burning engine.

As everyone struggled to disembark from the stranded DC-3, the Zeros returned for another attack. Flight engineer Joop Blaauw was wounded in both knees while trying to open the plane’s door. Most passengers and crew sought refuge beneath the wreckage or fled to the dunes. After the Zeros departed for Timor, Jo Muller sent out an SOS signal via the radio.

Using parachutes, they constructed a makeshift tent in the dunes. Hendrick van Romondt attempted to secure the mail, logbook, and a mysterious package entrusted to them by station master Wisse. Regrettably, while leaving the DC-3, Van Romondt was engulfed by a wave, causing the enigmatic package to vanish into the sea. Smirnoff dispatched two men, including Cramerus, to search for drinking water, but they returned empty-handed.

Tragically, Maria Van Tuyn and Joop Blaauw succumbed to their injuries that evening, and Daan Hendriks passed away on the morning of March 4. In a desperate bid for help, Smirnoff sent four men – Van Romondt, John ‘Jo’ Muller, Sergeant G.D. Dick Brinkman, and Lieutenant Pieter Cramerus – towards Broome.

Cramerus, despite his shoulder and head injuries, persevered through the pain and set off with his companions in search of assistance. The arduous journey proved challenging, exacerbated by the lack of drinking water, causing disorientation and stranding them in the wilderness. On the brink of exhaustion, they were fortuitously discovered after four days by an Aboriginal who provided water and kangaroo meat. Cramerus suffered severe sunburn, losing his clothes and shoes while crossing a creek. The Aboriginal advised them to spend the night in the bush and continue to Beagle Bay Mission the following day. Another Aboriginal, witnessing the DC-3 crash on the beach after the dogfight, rushed to Beagle Bay Mission to alert authorities, leading to a rescue mission. There is a video interview with Pieter Cramerus: “Lack of drinking water”.

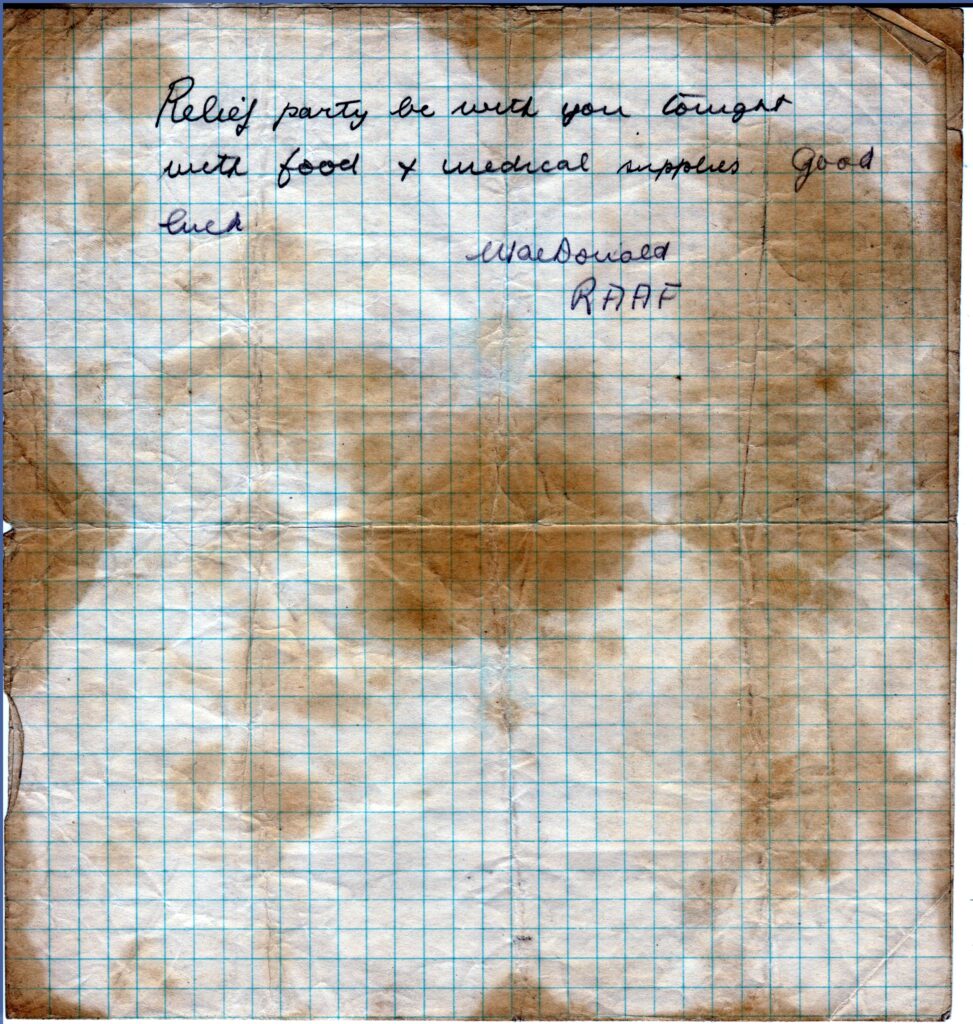

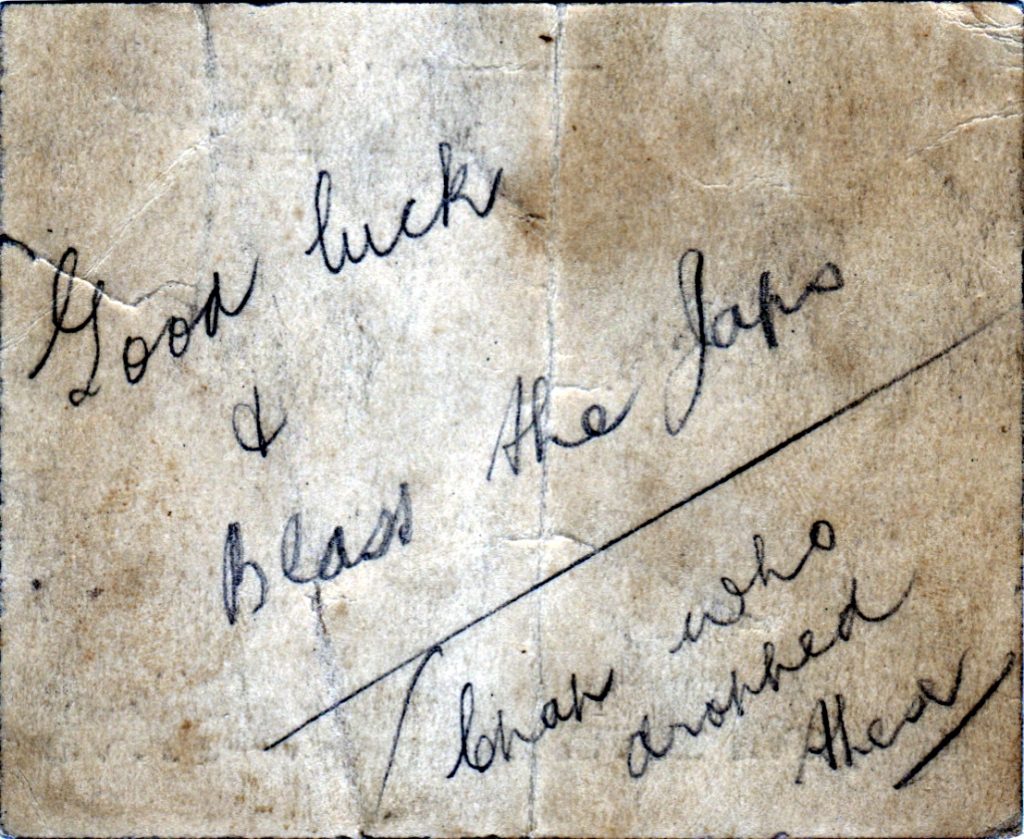

On March 6, two RAAF Wirraways dropped food and canned milk with a message promising a rescue party’s arrival that evening. At 3 a.m. on March 7, the rescue team arrived. Unfortunately, their arrival was too late for 12-month-old Johannes Van Tuyn, who passed away three days after his first birthday. The group left the crash site the following morning to trek the 40 kilometers to Beagle Bay Mission on foot, and two days later, they were transported by truck to Broome.

Below two photos of the ejected crumpled pieces of paper with handwritten scribbles by the crew of the RAAF aircraft, which the crew discovered on the beach near the shot down aircraft. (Source: Aviodrome Historical Aviation Archive)

Sometime later, while Smirnoff was in Melbourne, the police and a representative from The Commonwealth Bank paid him a visit, inquiring about the confidential package. It was then revealed that the package contained hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of diamonds. Smirnoff could only recount his experiences and had no knowledge of the valuable contents. However, this was not the end of the saga.

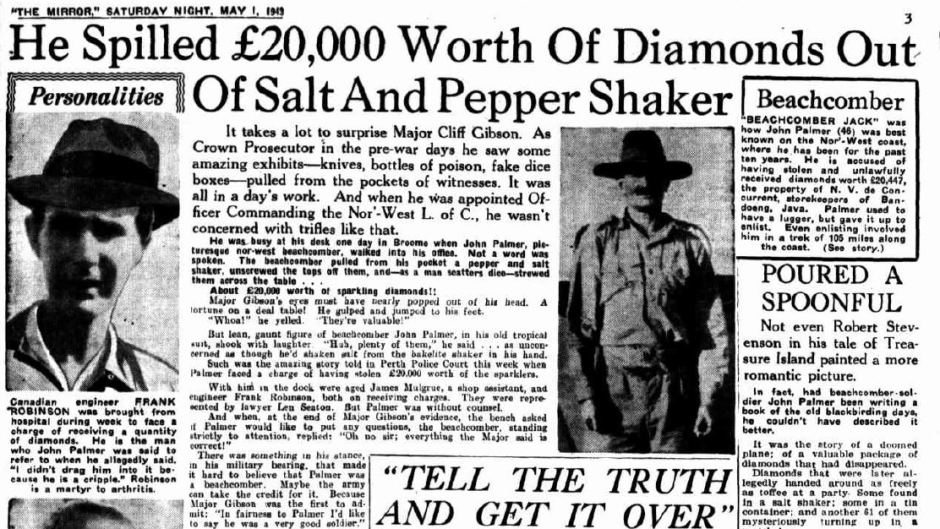

Beachcomber Jack Palmer sailed to the DC-3 wreckage site and began salvaging useful items. It is believed that Palmer stumbled upon the package and purportedly shared his findings with friends and Aboriginal individuals. In April 1942, Palmer reported to the army post in Broome and returned some diamonds to Major Clifford Gibson, concealed within a saltshaker. The diamonds were sent to Perth, and Palmer was compelled to reveal the location where he found the case. Despite extensive searches, only some parts of the DC-3 were recovered from the scene. Palmer and his associates faced trial in May 1943 but were acquitted. Over the years, sporadic discoveries of diamonds were made, yet the majority remained lost. The diamonds, valued at millions today, continue to be a tantalising, unrecovered treasure.

Pictures taken during the investigation after the crash.

See also: