The declassified original secret and top secret documents are in the pdf file at the end of this article.

Change of support

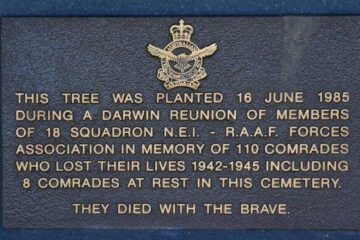

Australia promptly and unconditionally welcomed the Dutch after the fall of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) in 1942. They wholeheartedly supported the establishment of the NEI-in-exile on their soil, providing them with extraordinary extraterritorial rights.

However, influenced by actions from trade unions, the Australian Labor Government was compelled to take notice of the Indonesian independence movement. As the war concluded, the government had to confront the reality that the Dutch’s stubbornness on this issue was creating an untenable situation for them. Australia’s stance toward the conflict began to shift, and they actively urged the Dutch to negotiate with the ‘Indonesians.’

Upon his return to the NEI, Governor General of the NEI Huibert van Mook quickly grasped that the Dutch would be unable to quell the independence movement. Even before the war, he had cautioned the government in The Hague to formulate policies for managing this process. However, his government in the Netherlands was unwilling to confront this reality.

Australia assumed a pivotal diplomatic role in the unfolding process that eventually led to the full independence of Indonesia.

Australia’s leadership in the formation of the UN (see below) was driven by the precarious situation the country faced when it did not receive support from Britain in the defense of the country after the Fall of Singapore in 1942. It became evident that smaller countries needed to collaborate to secure a voice in international affairs. One of the first conflicts this new body became involved in was the Dutch-Indonesian conflict, and Australia played a crucial role in these proceedings.

The important role of Doc Evatt

In October 1941, Herbert Vere Evatt (‘Doc’ Evatt) assumed the position of Australia’s Minister for External Affairs in the wartime Labor government of John Curtin. Reflecting the general lack of independent Australian foreign affairs policies at the time, Evatt initially displayed little genuine interest in the subject, being relatively inexperienced in this field.

However, this quickly changed, transforming him into a diplomat often regarded as one of the best Australia has ever had. Evatt actively participated in conferences that ultimately led to the establishment of the United Nations, where Australia successfully advocated for a more significant role for smaller countries. Over the subsequent years, Australia assumed a leadership role in various pre-UN conferences and discussions.

The first meeting, convened in 1941, included representatives from Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia, and France.

During the UN foundation conference in San Francisco in 1945, the Australian delegation, led by Evatt, proposed a series of amendments. With the backing of other smaller nations, Evatt successfully expanded the scope of the General Assembly, bringing its powers closer to those of the Security Council.

His second major accomplishment was securing greater recognition of social and economic roles for the new organisation. Member nations pledged to work towards freedom for all, respect for human rights, full employment, and improved living standards.

Evatt later served as the President of the UN General Assembly from 1948 to 1949, playing a crucial role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Due to his fervent advocacy during the San Francisco conference, the General Assembly voted for Australia to hold a non-permanent seat on the Security Council.

During this period, Australia played a pivotal role in UN negotiations concerning the independence of Indonesia and, later, the handover of Dutch New Guinea to Indonesia.

See also: Founding of the UN

Linggadjati Agreement

After World War II, the Dutch found themselves at a disadvantage, facing delays in the re-occupation of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). During this period, the newly proclaimed Republic of Indonesia seized the opportunity to firmly establish itself on the main islands of Java and Sumatra.

In this weakened position, the Dutch were open to negotiations with the Indonesians, leading to the Linggadjati Agreement, named after the village on Java where the negotiations took place. The agreement was signed in November 1946.

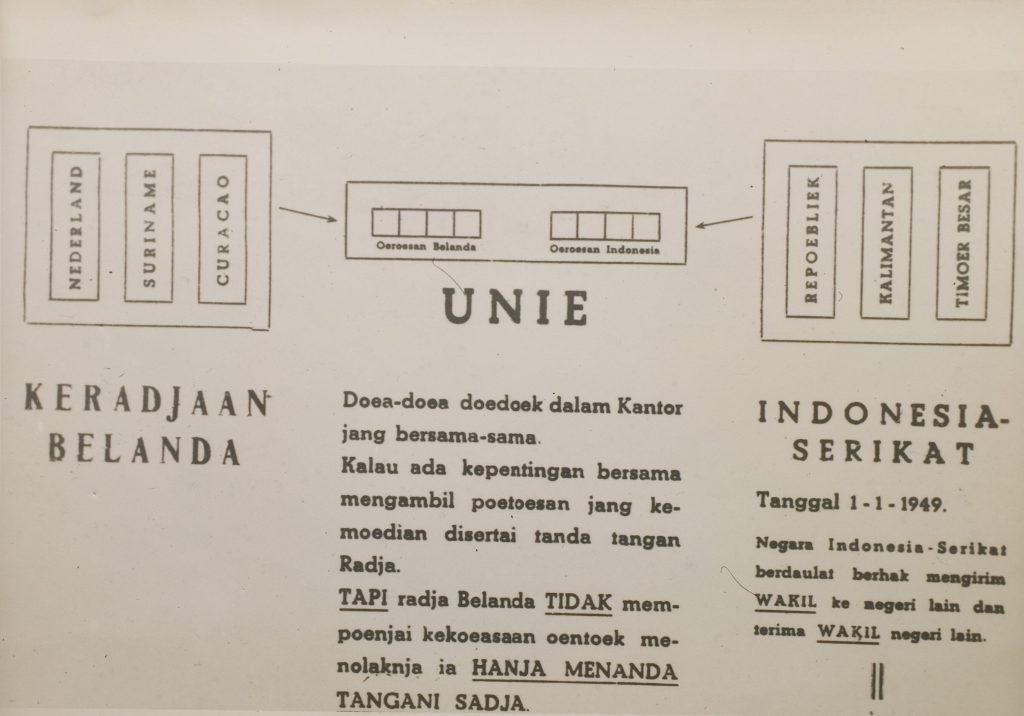

According to the terms of the agreement, the Netherlands recognised Republican self-rule over Java, Sumatra, and Madura. The Netherlands retained control over the rest of the archipelago, known as the State of Borneo and the Great Eastern State.

The Netherlands East Indies, along with the Netherlands, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles, would form a Netherlands-Indonesian Union, with the Dutch monarch serving as the official head of this Union.

As the Dutch began to increase their military presence in Indonesia, they became less inclined to adhere to the agreement. Eventually, differing interpretations on both sides prevented the full implementation of the Linggadjati Agreement.

Operation Product (Eerste Politionele Actie)

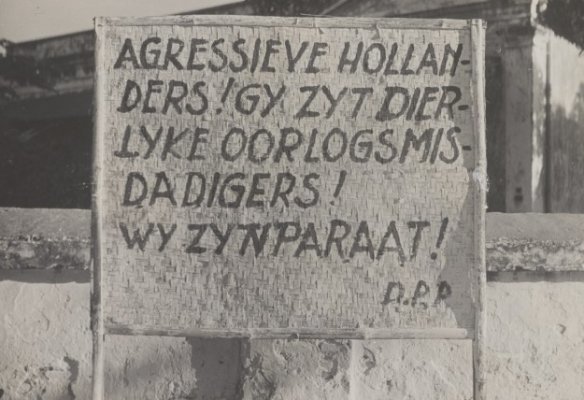

With the initial diplomatic attempt failed, the Dutch Government decided to employ military force to regain control over those parts of the archipelago still under the control of the Republic. The Dutch euphemistically referred to this colonial war as ‘police actions.’ Believing the resistance to be minimal, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) estimated that within a period of 3 to 6 months, they could quell the guerrilla activities of ‘the enemy.’ The first military operation, known as ‘Operation Product,’ occurred from July 21 to August 5, 1947, capturing rebel-held areas in Java and Sumatra. While largely successful, it resulted in a further radicalisation of the Indonesians.

International condemnation was swift, and on July 30, Australia brought the conflict to the attention of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), identifying the Netherlands as the violators of peace. Subsequently, Australia raised the broader matter of Indonesia’s decolonisation in the United Nations. Two days later, the UNSC ordered a cease-fire and established a committee to facilitate a truce and a resumption of negotiations.

Source: all six pictures below are from the Netherlands Royal Army Archives.

Amateur movie of the first Police Action in the NEI

From the Netherlands Royal Army Archives.

The film is about the entry into Loeboekpakam (East Sumatra). Cars arrive. Meetings and conversations on a veranda between civilians and soldiers.

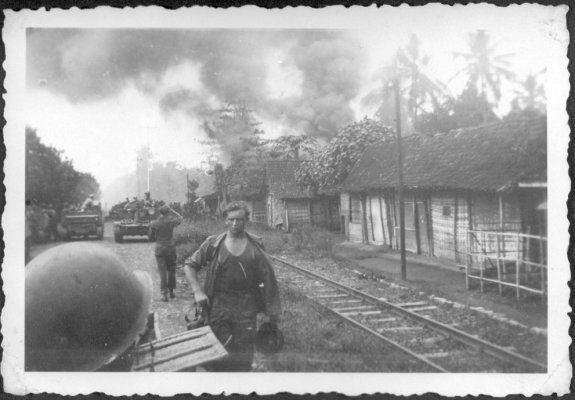

Then smoldering remains of a largely razed street in the town of Deli Toea (Deli Tua). The piles of rubble mark burned down Chinese shops and a column of vehicles stands still on a road in the forest.

A number of bren carriers in the forest. Group of soldiers travels through the jungle on foot. Two soldiers jump out of the bush. Soldiers clear a road and the edge of the forest of mines and explosives.

A column of bren carriers is removed. KNIL soldiers with captured pemudas (young freedom fighters) and captured weaponry. Clouds of smoke rise from the forest in the distance.

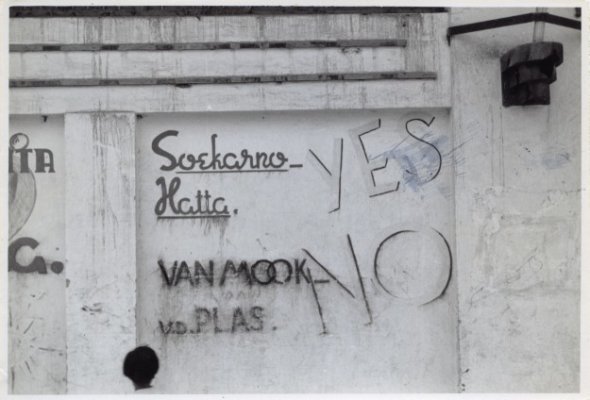

The camera passes a bridge on which a badly damaged car. Images of the burning remains of a city. A sign with a propaganda poster that later appears close-up. Burning houses in a deserted street. The Republican flag flies here and there. A soldier (camo uniform, Peloporpet) walks cautiously through the street.

Soldiers on a sports field fire a number of cannons (whether this is an exercise or actual combat operations is not certain).

Placard of the Partai Komenis Indonesia with hammer and sickle. Republican pamphlet directed against the RVD (depicted as a poisonous snake).

Images of burning houses and remains of TNI fighters (Tentara Nasional Indonesia – Indonesian National Armed Forces). Chinese Security Corps (Po An Tui).

Finally, lengthy images of a pro-Dutch demonstration by Indonesians in honor of Queen Wilhelmina. The demonstrators carry banners with her name and Dutch flags. At the very end some short shots of a roadblock with trees.

The Committee of Three

In response, the Security Council passed a resolution, proposed by the United States, offering its good offices to peacefully resolve the Dutch-Indonesian dispute. This assistance materialised in the form of the United Nations Good Offices Committee Indonesia (UNGOC), consisting of three representatives—one appointed by the Netherlands, one by Indonesia, and a third agreed upon by both sides. The Dutch selected a representative from Belgium, Indonesia chose Australia, and both agreed on the US for the third member.

Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley proposed to host the conference in Australia, a suggestion accepted by the Republic but declined by the Netherlands.

Australia’s shifting position on NEI

Until 1947 and the first Dutch ‘police action,’ the Australian government had been leaning towards the continuation of Dutch sovereignty in the NEI, envisioning a scenario in which Indonesians would enjoy substantial self-government.

Amid the deteriorating situation in Indonesia in 1948, the Labor government’s stance on resolving the conflict increasingly shifted towards supporting Indonesian sovereignty within the Netherlands-Indonesian Union proposed in the Du Bois-Critchley plan.

It became evident to the Dutch that Australia had taken a pro-Indonesia position on the issue, causing clear disappointment as this stood in stark contrast with Australia’s initial support for the recolonisation of the NEI. However, Australia was not alone in this shift, as the Dutch found themselves increasingly isolated, facing international opinion turning against them. The relationship between the Netherlands and the USA had notably soured during the discussions within UNGOC.

On the Australian side, this gradual evolution of support for Indonesian independence became increasingly tied to the belief that a stable, independent Indonesian state would offer greater security for Australia. Generally, the Labor government demonstrated a more realistic understanding of the strength of the nationalist movement in Indonesia compared to the Liberal opposition. Additionally, the Labor government was more committed to establishing future Indonesian-Australian relations on a solid initial footing.

See also: Australian attitudes and policies towards Indonesia 1950 to 1965 – Nancy M. Viviani

Renville Agreement

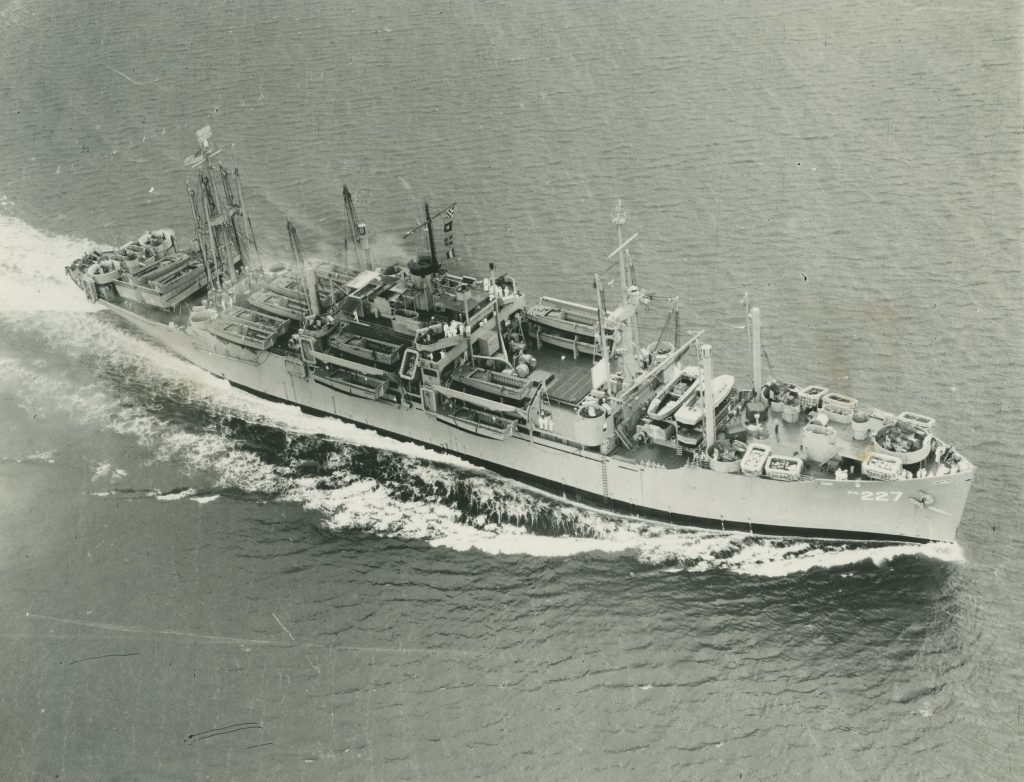

As a result of the UNGOC negotiations, a new conference was organised, taking place on January 17th, 1948, on the US ship Renville in the Bay of Batavia. The outcome became known as the Renville Agreement, rectifying the collapsed Linggadjati Agreement.

The key element of the agreement stipulated that Dutch sovereignty would persist until transferred to the United States of Indonesia, with the Republic of Indonesia as one of its components. Other provisions included fair representation for each component of the provisional federal state in its government, a referendum within six months to determine regional affiliation with either the Republic of Indonesia or the United States of Indonesia, and a constitutional convention to draft a constitution. Additionally, any state would be free to abstain from joining the Republic.

Colonel Abdulkadir Widjoatmodjo, an Indonesian (Indo) civil service official, ratified the agreement for the Netherlands. Later, he became the deputy of Jhr Heinrich van Vredenburch, who led further Dutch-Indonesian independence negotiations.

Despite the Renville Agreement, mutual distrust between the Netherlands and the Republik persisted. During the lead-up to the Renville conference, a military action on December 9, 1947, resulted in Dutch troops massacring over 400 civilians, primarily men, in the village of Rawagede in West Java.

Opposition from the left, particularly the Communist Party in Indonesia, was strong, viewing the agreement as an increased influence from the USA. In February 1948, shortly after the agreement was signed, the Siliwangi Division (35,000 men) of the Republican Army, led by Nasution, breached the ceasefire line, marching from West Java to Central Java. The Dutch leadership found itself increasingly losing control.

Subsequent negotiations led to the Du Bois-Critchley Plan, named after the US representative Coert du Bois and the Australian representative Tom Critchley. This plan offered detailed suggestions for the principles of a political agreement between the Netherlands and the Republic of Indonesia, forming the basis for the sovereign United States of Indonesia in equal partnership with the Kingdom of the Netherlands in a Netherlands-Indonesian Union.

However, six months after the signing of the Renville Agreement, the Committee reported its inability to secure agreement on its implementation from the warring parties. The primary obstacle was the strong animosity in the Netherlands towards UNGOC, as it supported a greater say for the ‘Indonesians’ in shaping their own future (full independence was still not on the agenda at this stage).

With lackluster support from the Dutch, its military command pressed on to continue the war, aiming to capture the rebel-held city—and headquarters of the resistance—Yogyakarta. The threat of communism was emphasised by the Dutch military as a key reason to continue the war against the Republik. It gained strong support from the ministers of the co-governing Catholic People’s Party (KVP) in the Netherlands. However, their coalition partner, the Labour Party (PVDA), opposed it, fearing strong opposition from the UN Security Council. Simultaneously, they distrusted propaganda from the KNIL and the NEI government.

Operation Crow (Tweede Politionele Actie)

Following Parliamentary elections in 1984, a broad four-party coalition government was formed between the Catholic People’s Party, Labour Party, Christian Historical Union and People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy. Combined these parties held 76% of the available seats in parliament.

This right wing coalition decided to embark on a second military intervention (Operation Crow), which occurred between December 19, 1948, and January 5, 1949. The Dutch successfully captured Yogyakarta, imprisoned most of the political leaders, and controlled major transport corridors between the main cities. However, they failed to defeat the Republik’s guerrilla army, which essentially held sway in most areas outside the major cities. This second military operation prompted international condemnation, led by the UN, and even drew a threat from the USA to halt the Marshall Aid funds to the war-ravaged Netherlands, which were already worth $1 billion at that time.

The Marshall Plan was an American initiative to aid Western Europe, in which the United States gave over $44 billion in economic assistance to help rebuild Western European economies after the end of World War II.

Source: all six pictures below are from the Netherlands Royal Army Archives.

Frustrated by the relatively weak international response to the second Dutch offensive, Australia participated in an Asian Conference convened by India’s Prime Minister, Nehru, in New Delhi. The aim was to coordinate regional support for the Indonesian Republic. This unprecedented display of regional solidarity in New Delhi undoubtedly influenced a majority in the Security Council to order, on January 28, 1949, the restoration of the imprisoned Republican Government to its capital, Yogyakarta, and the resumption of negotiations between this Government and the Netherlands.

As early as August 1947, under the auspices of UNGOC, Australian military observers were stationed in NEI, and their numbers increased after the second Dutch military operation in 1949. By that time, UNGOC had been upgraded to the United Nations Commission for Indonesia (UNCI). The Australian force was eventually withdrawn in April 1951, marking Australia’s pivotal role in the first-ever UN Peacekeeping operation deployed in the field.

The Beel Plan

The Dutch were finally brought to their knees, compelling them to formulate a plan as mandated by the UN. Named after its originator, Louis Beel, the plan aimed to transfer sovereignty—without first restoring the Republic—to an Indonesian Federal Government that the Dutch would create and indirectly control.

Australia actively opposed the Beel Plan, urging the Dutch to prioritise the restoration of the Indonesian Republic. Without this step, genuine negotiations for Indonesian independence would be impossible. Australia even threatened to bring the matter to the UN General Assembly. Faced with international pressure, the chief Dutch negotiator in Batavia, J.H. van Roijen, reached an agreement on May 7, 1949, with a Republican delegation led by Mohammed Roem, assisted by Australia’s diplomat Tom Critchley.

Under this agreement, the Republic committed to ceasing hostilities against the Dutch army, and in return, the Netherlands agreed to restore the Republican Government to Yogyakarta.

On July 5, 1949, Sukarno and Hatta returned triumphantly to Yogyakarta, marking a significant symbolic occasion. It was the first time the Dutch were compelled to relinquish territory they had held.

The Hague Conference

This was followed by the so-called “The Hague Conference” (from 23 August to 2 November 1949).The Conference’s task was to negotiate the transfer of sovereignty to an Indonesian Federal State. The Conference faced significant challenges, particularly concerning the status of West New Guinea and the issue of debts to be assumed by the new Indonesian State. Tom Critchley played a crucial role in brokering an agreement on both matters. Firstly, he encouraged the parties to defer the issue of West New Guinea to post-independence political negotiations. Secondly, he advocated for the reduction of debts to be taken over by Indonesia.

The final agreement resulted in the transfer of sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia—this time fully under the control of the Republik but in union with the Netherlands and its other overseas territories: Surinam and its territories in the Caribbean.

In total, around 150,000 Dutch forces were engaged in the two military operations, resulting in the deaths of over 100,000 ‘Indonesians’ and 5,000 Dutch soldiers (half of whom succumbed to disease or accidents). Seventy years later, court cases in the Netherlands continue as ‘Indonesians’ pursue justice for the torture endured during the so-called police actions in the war of independence.

All in all the war in Indonesia cost the Netherlands over US$500 million (worth the equivalent of US$5 billion in 2018), at a time they could hardly afford it as they were rebuilding their own country after the war with Germany.

The Aftermath

This Commonwealth arrangement, however, never materialised, and by 1957, that treaty was invalidated by the ‘Indonesians.’

As a consequence, Sukarno nationalised 246 Dutch companies that had been dominating the Indonesian economy, notably the NHM, Royal Dutch Shell subsidiary Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, Escomptobank, and the “big five” Dutch trading corporations (NV Borneo Sumatra Maatschappij / Borsumij, NV Internationale Crediet- en Handelsvereeneging “Rotterdam” / Internatio, NV Jacobson van den Berg & Co, NV Lindeteves-Stokvis, and NV Geo Wehry & Co). Additionally, he expelled the 40,000 Dutch citizens remaining in Indonesia while confiscating their properties. Sukarno’s key argument was the Dutch government’s failure to continue negotiations on the fate of Netherlands New Guinea, as promised in the 1949 Round Table Conference.

The profound impact of all this on the Dutch is evident in the fact that it wasn’t until 2005—during a visit from Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands—that the Dutch finally recognised the 17th of August 1945 as the birth of Indonesia, not the date on which sovereignty was transferred on November 2, 1949.

The Dutch-Indonesia conflict also had an unprecedented effect on Australia’s foreign policies. Until 1942, it had largely depended on British guidance on international issues. The conflict led to Australia’s first major independent political relationship with an Asian country, pulling it out of its very narrow national perspective, largely dominated by its White Australian Policy that persisted.

Australia’s active involvement, first in assisting the Dutch in establishing the NEI government-in-exile on its soil and subsequently in the unfolding conflict, saw many Australians actively or passively engaged in an international issue. For the first time, Australia played a significant role as an independent country on issues that were, on many occasions, not supported by the British.

After an initial alignment on the issue of Netherlands New Guinea, Cold War politics saw Australia again shifting its alliance from the Netherlands to Indonesia.

The Australian Labor government was ousted in 1949 and was followed by 17 years of a Coalition Government of the Liberal Party and the Country Party, led by Robert Menzies (1949-1966). During the and after the war it had largely support the Dutch position and had been rather hostile towards the Indonesian independence movement.

Now in power the more right-wing Australian government adopted a hostile attitude to The Republik of Indonesia, supplying arms to rightist military rebels who were fighting against the Indonesian government. Furthermore, it used propaganda as well as diplomatic and military opposition directed at the anti-imperialist policies of president Sukarno in the 1960s. This difficult period of conflicted Australian – Indonesian relations has until now often overshadowed the very close link that had been established during those early years of the Republik.

Australia kept maintaining its White Australian policy, which upset many of the Asian countries reminding them of the arrogance of the ‘white man knows best’ attitude and of colonialism. In the end the only result was the ANZUS pact between Australia, New Zealand and the USA which started in 1951. The broader regional alliance was formed in 1967 as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) of which Australia was finally admitted as a member in 2005.

West New Guinea

Until 1949, West New Guinea was part of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI), and for that reason, Indonesia claimed it as part of its territory. The Dutch argued that it was a distinct ethnic entity and should not be included in the transfer of sovereignty, citing historical agreements to strengthen their case. As negotiated by Australia, Indonesia accepted this condition with the understanding that the matter would be discussed later.

However, subsequent negotiations failed to reach a resolution. While Indonesian concessions exceeded those offered by the Dutch, the prevailing political sentiment in the Netherlands leaned towards keeping New Guinea as part of the Dutch Commonwealth.

Initially supporting Indonesia’s claim, Australia’s position shifted as Sukarno distanced the country more from the West, raising concerns that it might fall under communist influence. Australia was wary of having a communist state at its borders.

The New Guinea issue played a pivotal role in Indonesia unilaterally ending the Netherlands-Indonesian Union in 1957. Belatedly, the Dutch increased governance, education, and healthcare activities in New Guinea, aiming to prepare it for self-determination. My aunt, Annie Budde, was involved in these efforts, but limited resources and limited time hindered effective preparation of the local population. Sukarno strategically negotiated with the USSR for the supply of heavy military equipment, previously denied by the USA to Indonesia. Subsequently, President John F. Kennedy announced that he would prioritise New Guinea on his personal agenda.

The USA influenced the UN, prompting Australia to change its position in favor of Indonesia’s demands. The Black Armada boycott was reinstated, and Dutch ships en route to New Guinea were denied service in Australian ports. On August 15, 1962, the Dutch handed over West New Guinea to the UN, and a year later, it was transferred to Indonesia. The promised referendum for self-determination in 1969 was manipulated, resulting in New Guinea becoming a province of Indonesia.

Like many others, my aunt supported Free Papua until her death in 2009. Eventually, similar to Indonesia’s independence from the Netherlands, the aspirations of the people may prevail over time.

Paul Budde

January 2024

Declassified Australian documents in relation to the Indonesia Question

The Indonesian Question was also researched in the National Archives of Australia by Ruby Todorovski, a researcher at the University of Queensland. The file below is in chronological order, starting with a personal letter highlighting the political tension of the day, followed by the declassified documents.

The strain in Netherlands-Australian relations became more apparent with the reversal of the Australian Government’s initial decision to host the training of 30,000 Dutch troops. As Australia, Britain, and America reduced their military presence in the Far East, the Netherlands sought to bolster its forces in the Netherlands East Indies. Despite this pressing need, Australia ultimately declined to cooperate, leading to the relocation of the troop training activities to the Netherlands itself.

Links to other declassified WWII Australian Documents re the Netherlands East Indies

The Colonial war could have been prevented

General Schilling’s prescient warnings about the military risks in the Dutch East Indies in 1945 and 1946 were ignored. The Dutch military force in the Dutch East Indies from 1945 to 1950 failed to subdue the newly formed Republic of Indonesia. Despite warnings from General Schilling, the Netherlands opted for large-scale military action to enforce Dutch rule, alongside intermittent negotiations.

The end of World War II saw Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945, followed by the declaration of an independent Republic of Indonesia in Jakarta two days later. This left the Netherlands grappling with the question of its role in the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch government aimed to regain control of the region before gradually allowing Indonesians to pursue independence. However, General Schilling’s warnings about the difficulty, if not impossibility, of a military solution were disregarded.

Schilling, born in 1890 in Enschede, Netherlands, had extensive military experience in the Dutch East Indies, particularly in Aceh. Despite his insights, the Dutch government, influenced by optimistic views of younger military officers like Colonel Spoor, opted for a military solution. This decision led to two “police actions” in 1947 and 1948, but they failed to quell Indonesian resistance, resulting in significant casualties.

Moreover, there was a reshuffling of top military positions, with Schilling being sidelined despite his experience and foresight. Instead, Colonel Spoor, whose military strategy aligned with the government’s approach, was favored. Schilling was later appointed head of the Dutch military mission in Tokyo.

In hindsight, Schilling’s warnings about the challenges of military action in Indonesia were proven accurate. The Dutch government’s underestimation of the Indonesian resistance, coupled with political and military mismanagement, prolonged the conflict and led to significant human suffering.

Full article in Dutch: Eén generaal in Indië zag het goed | Historiek